Crocodile eyes are fine-tuned for lurking

- Published

This is the first time the crocodile retina has been studied in such detail

A new study reveals how crocodiles' eyes are fine-tuned for lurking at the water surface to watch for prey.

The "fovea", a patch of tightly packed receptors that delivers sharp vision, forms a horizontal streak instead of the usual circular spot.

This allows the animal to scan the shoreline without moving its head, according to Australian researchers.

They also found differences in the cone cells, which sense colours, between saltwater and freshwater crocs.

Published in the Journal of Experimental Biology, external, the findings suggest that although the beasts have very blurry vision underwater, they do use their eyes beneath the surface.

This is because light conditions are different in salt and freshwater habitats, but only underwater - and the crocodiles' eyes show corresponding tweaks.

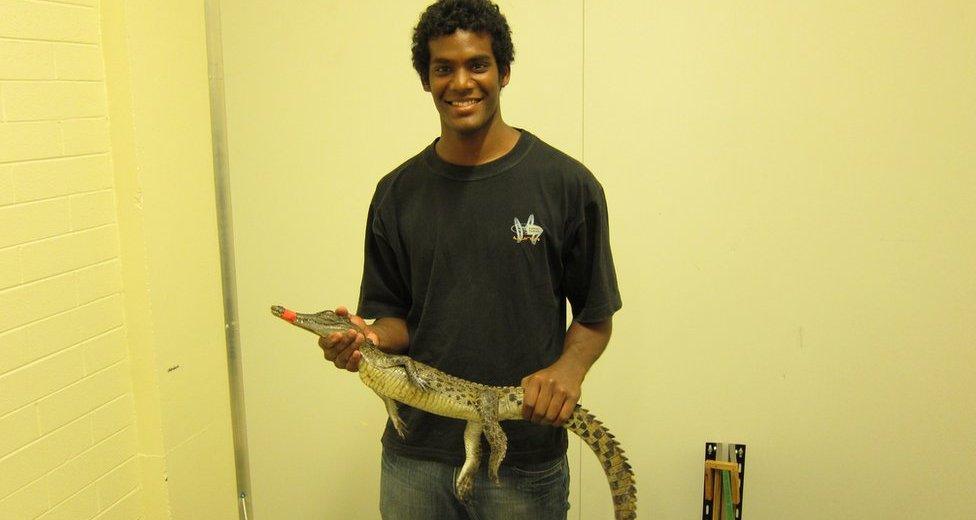

Experimental subjects, like this saltwater specimen, were two-year-old crocs up to 1m long

"There's generally more blue light in saltwater environments, and more red light in freshwater environments. Animals tend to adapt to this," explained Nicolas Nagloo, a PhD student at the University of Western Australia.

He and his colleagues studied eyeballs from juvenile "salties" and "freshies", shipped to the university from a crocodile farm in Broome.

When they measured the light absorbed by single photoreceptors in the retina, they found that those of the freshwater crocs were shifted towards longer, redder wavelengths compared with their saltwater cousins.

Finding this skewed sensitivity in crocodiles was unexpected, Mr Nagloo said, because the famous predators were only semi-aquatic and did their hunting, feeding and mating on land.

What are crocodiles doing with their blurry underwater vision?

"It's surprising because these guys can't actually focus underwater. [But] light sensitivity seems to be important to them," he told BBC News.

"That tells us there's potentially some aspect of their behaviour underwater that we're not aware of yet."

The team also studied the density of receptors across the crocodile retina. In this regard, the two species were more similar.

Overall, crocodile vision appears to be less precise than ours, achieving a clarity some six or seven times lower than the human eye. But their "foveal streak" is a striking adaptation that suits their lifestyle perfectly.

The fovea is a dent in the retina, containing a huge concentration of receptor cells. The indentation arises because other cells, which transmit visual information to the brain, are shifted to the sides.

Each retina was spread out on a microscope slide to study its properties

"Typically, the fovea is circular and located in the centre of the retina. It provides animals with an area of very high visual clarity, in a small area of their visual environment," Mr Nagloo said.

It is this small patch of high-resolution information that allows us, for example, to read; but we humans have to move our eyes around to drink in details across a scene.

"In the case of crocodiles... it's spread across the middle of the retina, and it gives them maximum clarity all along the visual horizon."

This arrangement reflects the predator's iconic ability to lurk with just its eyes above the water, waiting motionless for prey to wander too close to the river's edge.

Mr Nagloo and his colleagues received the crocodiles from a farm in Broome, Western Australia

Other animals, particularly mammals like deer and rabbits that live in open spaces and themselves face predation, are known to possess a similar "visual streak". But that is a more subtle feature than the furrow-shaped fovea of the crocodile, Mr Nagloo said.

"A visual streak is just an elevated cell density, in an elongated shape. A fovea takes that to the extreme - the number of photoreceptors is so high that they have to move the transmitters away, to make room for them. So the wiring is different.

"I haven't seen any other animals with this kind of specialisation."

Follow Jonathan on Twitter, external