Europe races to meet Orion deadline

- Published

Artist's impression: The conical Orion capsule sits in front of its European service module

European industry has begun assembling the "back end" of the Orion crewship that is due to make an important 2018 demonstration flight around the Moon.

Orion is the next-generation vehicle, external that the US space agency (Nasa) will use to send astronauts beyond Earth, to destinations like asteroids and Mars.

But it needs a "service module" to provide propulsion, power, temperature control, and to carry water and air.

That job will be done by the unit now being built by Airbus in Germany, external.

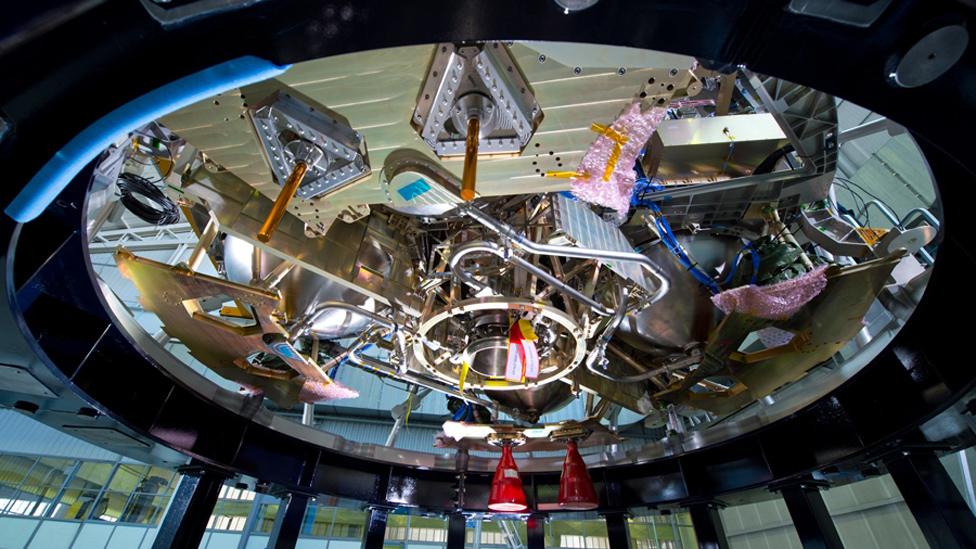

It is an immense piece of hardware, external in the shape of a 4m-wide cylinder. In flight configuration, it will weigh some 13 tonnes.

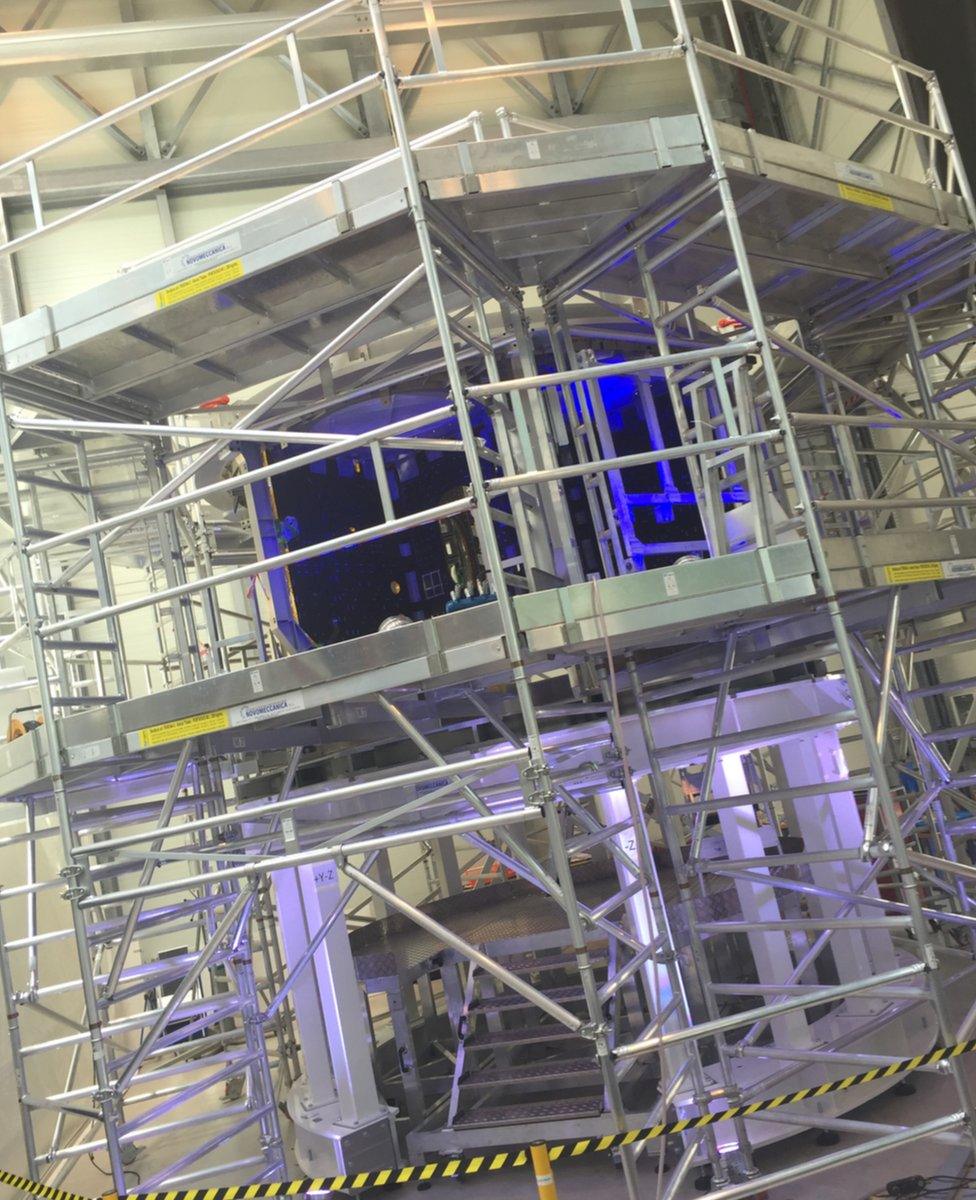

"What you see at the moment is just the primary structure, but over the coming months the empty space within it will be packed," said Philippe Deloo, the top European Space Agency (Esa) official overseeing the project.

"What needs to go in is the propulsion system, the power system, the thermal system, and the consumables storage - the items that deliver water and gas to the [Orion capsule]. All have to be integrated and verified to complete the vehicle."

The service module is just a shell at the moment

This is the first time the Americans have gone overseas for a critical element of one of their astronaut transportation systems.

The key parts for Mercury, Gemini, Apollo and the space shuttles were all US-made.

"[Europe's] position on 'the critical path' has never been done before, and to be frank: we do not fly without the service module," stressed Jim Free, a Nasa deputy associate administrator.

No 'big contingencies'

Mr Free attended a ceremony in Bremen on Thursday to kick off the latest construction phase. He was joined on the American side by representatives of the Orion capsule's prime contractor, Lockheed Martin.

Airbus is hopeful of getting the completed module out the door by early 2017 - a timeline the company acknowledges will be challenging.

The 2018 mission will see Orion and its service module launch atop the Space Launch System rocket

An indication of just how much pressure everyone is under can be seen in the fact that final assembly is proceeding even before the module has had its so-called Critical Design Review.

The CDR is usually the moment when all the final drawings are signed off; no further changes can be introduced.

But Bart Reijnen, who leads the service module project at Airbus, says he is very comfortable with the current state of affairs.

"It's true you don't see this on all space programmes, but it's something we do knowing the risk we are taking, managing that risk, and burning it down in the coming days and weeks.

"We have concluded it's a viable way or we wouldn't have done it, but it doesn't allow certainly for any big contingencies in the current schedule," he told BBC News.

Bart Reijnen: "We are burning down the risk"

Orion has already flown once, in 2014, making a quick sweep around Earth. For that unmanned sortie, it used a dummy service module.

That will not be the case for the next outing, in 2018, when the capsule (still without a crew) will be mated to its European aft section for a three-week loop behind the Moon.

Known as Exploration Mission 1 (EM1), external, the venture will also witness the debut of Nasa's new "monster rocket", the Space Launch System (SLS), external.

This Goliath will have the muscle to hurl the mission in the direction of the Moon, but it will be the task of the European service module to maintain the correct trajectory and to make the essential engine burns required to bring the capsule safely back to Earth.

One made earlier: Airbus has already built a test version of the service module

For the moment, Europe is formally committed to making just the one module. But Esa member states will be asked in December to put the funds behind a second unit. The current, first unit was priced with Airbus at 390m euros; a second module would be used on Orion's first manned outing, EM2, a mission scheduled for "no later than April 2023".

It would be a major surprise if the member states rejected the proposal. For one thing, the first module has been given "free" to Nasa as an in-kind payment to cover Esa's costs at the space station. If Europe does not offer another module, it will have to cover those ongoing costs in some other way.

But, more than all that, Orion and the SLS are regarded by many as the future of human exploration beyond Earth, and Europe wants to be - as Esa boss Jan Woerner put it - "part of that game".

"I hope we can convince the member states as well as Nasa that we should go beyond this first flight model, for a second and maybe even more, and through that having a barter element for European astronauts flying on the SLS system," the director general added.

If European participation does become routine - and Nasa is talking about one or two flights per year eventually - then an industrial role in the service module will likely have to be found for the United Kingdom. It only recently joined Esa's human spaceflight programme, and has no components in the first vehicle.

But it is entitled to some sort of manufacturing return on its Esa investment.

Agency and Airbus officials said on Thursday they were already looking at how that "juste retour" could be fulfilled in the future.

- Published9 November 2015

- Published17 September 2015

- Published5 December 2014

- Published18 November 2014