Ancient crayfish and worms may die out together

- Published

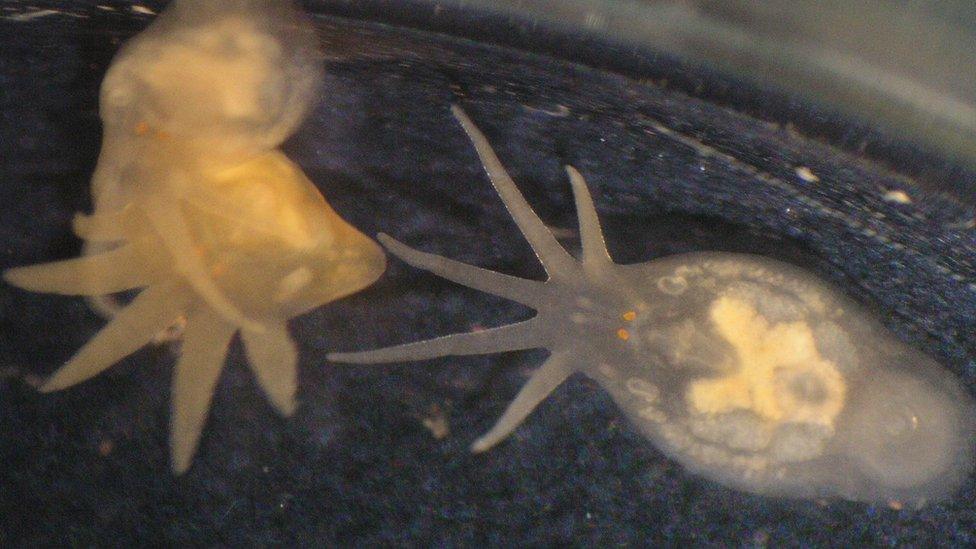

The crayfish and the "temnocephalan" worms have coexisted for up to 100 million years (footage: David Blair, James Cook University)

Research suggests that bizarre, tentacled worms which live attached to crayfish in the rivers of Australia are at risk of extinction - because the crayfish themselves are endangered.

It would be an example of coextinction, where one organism dies out because it depends on another doomed species.

Just a few millimetres long, the worms eat even tinier animals in the water or inside the crayfish gill chamber.

This symbiotic relationship stretches back at least 80 million years.

The new study maps out that shared history based on genetic analysis of 37 different species of spiny mountain crayfish and 33 varieties of their "temnocephalan" flatworm passengers.

Published in the Proceedings of the Royal Society B, external, it was a collaboration between Australian and UK scientists.

They compiled a detailed evolutionary tree of both groups of animals and integrated it with the species' geographical distribution.

This revealed a lengthy tale of shared evolution with an apparent starting date of 80-100 million years ago, as determined by a "molecular clock" calculation based on the steady accumulation of mutations.

At that time, Australia was about halfway through its gradual northward march to its current position on the globe. As the continent inched closer to the equator and steadily warmed up, the habitat of these creatures started to fragment and shrink.

The flatworms are a few millimetres long and vary in their shape

Today, spiny mountain crayfish - a genus called Euastacus - live in dwindling patches of eastern Australia. In the warmer, northern part of their range they are restricted to lofty forest streams.

Those northern crayfish lineages, as well as being closest to extinction, tend to be the most distinctive in their physiology and their DNA. The worms show a very similar pattern.

Dr Jennifer Hoyal Cuthill, first author of the paper, studies evolutionary patterns at the University of Cambridge.

She told BBC News: "Overall what we found was that in the north, where the crayfish live in cool streams on the top of hills and mountains where little patches of high-altitude rainforest are left, they're very isolated. So the worms that live on them are specialised and only live on that crayfish, and there's very little opportunity for them to switch hosts.

"In the south, there's a slightly different picture, where there's been more switching around."

Currently, three-quarters of the 37 Euastacus crayfish species are known to be endangered. The scientists found that if all those crayfish species were to die out, some 19 of the 33 temnocephalans would also disappear - starting with those in the north.

The Euastacus family is very diverse and includes the 10cm "lamington spiny crayfish"

They warn that such a sweeping coextinction is a genuine threat, particularly as modern-day climate change steepens the warming of Australia that has shaped and shrivelled the creatures' shared habitat over the millennia.

Forestry and other environmental changes add to the risk.

"In Australia, freshwater crayfish are large, diverse and active 'managers', recycling all sorts of organic material and working the sediments," said the study's senior author, Prof David Blair of James Cook University in Townsville, Australia.

"The temnocephalan worms associated only with these crayfish are also diverse, reflecting a long, shared history and offering a unique window on ancient symbioses. We now risk extinction of many of these partnerships, which will lead to degradation of their previous habitats and leave science the poorer."

Follow Jonathan on Twitter, external