Hubble clocks faster cosmic expansion

- Published

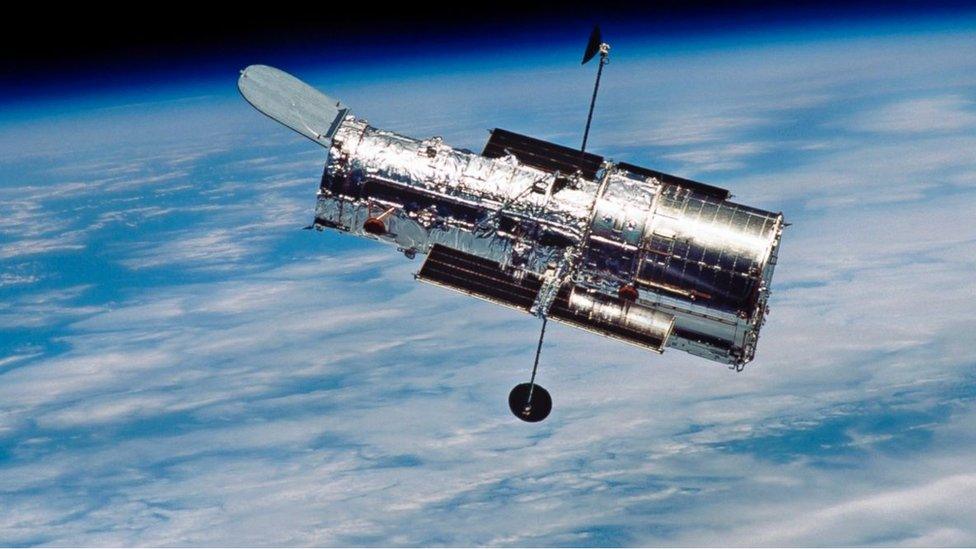

A Hubble Space Telescope image of UGC 9391, one of the galaxies in the new survey

The Universe may be expanding up to 9% faster than previously thought.

This new assessment comes from the Hubble Space Telescope, which has significantly refined the rate at which nearby galaxies are observed to be moving away from each other.

It reinforces the tension between what we see happening locally and what we would expect from the conditions that existed in the early cosmos.

These have implied a much more sedate trajectory for the recession.

Science now has a big job on its hands to try to resolve the conundrum, says Adam Riess, external from the Space Telescope Science Institute (STScI), external and the Johns Hopkins University, both in Baltimore, Maryland, US.

"To be honest, with this latest measurement we've really gone beyond what we might call 'tension'; we're missing something in our understanding of the cosmos," the Nobel Laureate told BBC News.

The issue at hand is the so-called Hubble Constant - the value used by astronomers to describe the current expansion.

It is a critical number because it helps us gauge the size and age of the Universe.

One of the telescope's main goals - and achievements - has been to refine the Hubble Constant

One way to pin down this value is to measure the distance and velocities of a large number of stars in a good sample of galaxies.

In Dr Riess's new study, external, to be published shortly in The Astrophysical Journal, external, this was done with the aid of two classes of very predictable stars.

These are the cepheid variables - pulsating stars that puff up and deflate in a very regular fashion; and a group of exploding objects referred to as a Type 1a supernovae.

Both shine with a known power output, and so by comparing this quantity with their apparent brightness on the sky, it is possible to figure out their separation from Earth and thus, also, the distance to the galaxies that host them.

Some 2,400 cepheids in 19 nearby galaxies were used in the survey, and these helped calibrate roughly 300 Type 1a supernovae, whose particular properties enabled the team to probe a slightly deeper volume of space.

The work gives a number for the Hubble Constant of 73.24 kilometres per second per megaparsec (a megaparsec is 3.26 million light-years). Or put another way - the expansion increases by 73.24km/second for every 3.26 million light-years we look further out into space.

It means basically that the distance between cosmic objects will double in another 9.8 billion years.

Artist's impression: Planck surveyed the oldest light in the Universe to understand its constituents

This is the third iteration of the project led by Dr Riess and has an uncertainty of just 2.4%.

But there is another way to determine the constant, and that is to look at the expansion shortly after the Big Bang and to use what we know about the contents and the physics at work in the Universe to predict a modern value of the expansion.

This has been done using data acquired by the Planck space telescope, which earlier this decade made the most detailed ever observations of the oldest light in the Universe.

Its Hubble Constant value was 66.53km/s per megaparsec.

The disagreement with Dr Riess's number is more than just a minor inconvenience. When using the Hubble Constant to calculate the time from the Big Bang, the offset equates to a difference of a few hundred million years in the near-14-billion-year age of the Universe.

The STScI scientist says the resolution is likely to be found in a better understanding of the "dark" components of the cosmos.

These include the unseen matter in galaxies (dark matter), and the vacuum energy (dark energy) postulated to be driving an acceleration in the expansion.

The gap could also be plugged by the existence of another, but hitherto undetected, particle.

The often-hypothesised fourth type, or flavour, of neutrino, external would fit the bill.

"This would change the balance of energy in the Universe and it would speed it up," Dr Riess said.

Answers will surely come from the new space telescopes and particle detectors due to enter service in the next few years, he added.

Jonathan.Amos-INTERNET@bbc.co.uk, external and follow me on Twitter: @BBCAmos, external

- Published23 April 2015

- Published17 February 2015