Melt ponds suggest no Arctic sea-ice record this year

- Published

Melt ponds are part of a feedback process that promotes melting

Arctic sea-ice extent is unlikely to see a new record this summer, claim polar experts at Reading University, UK.

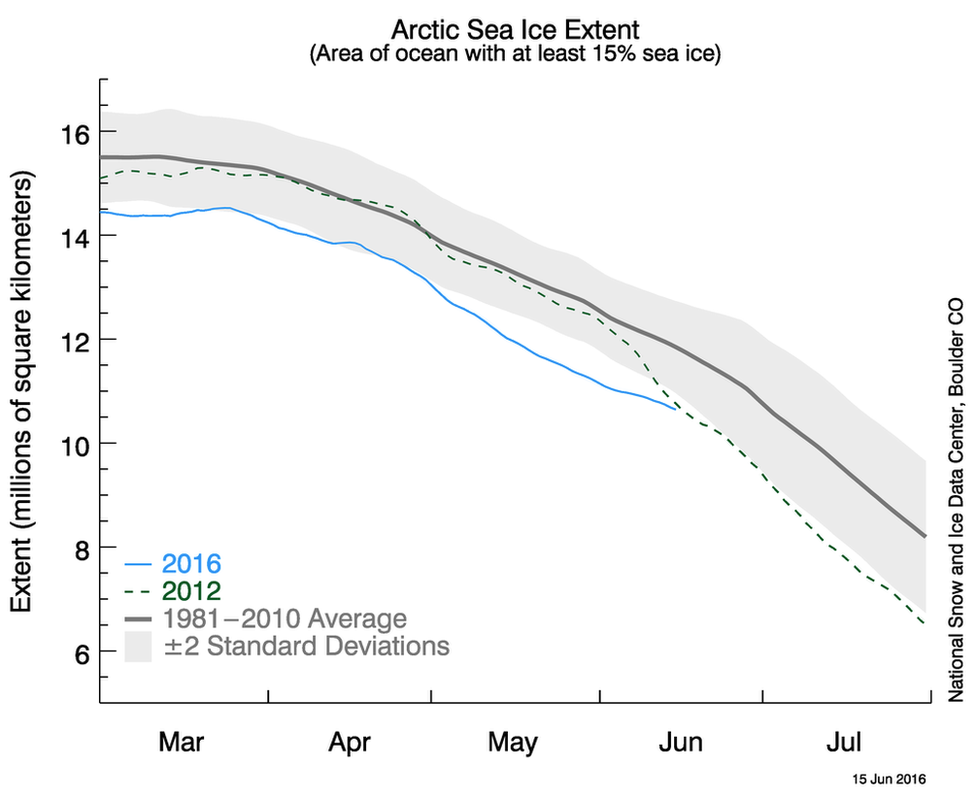

The floes have experienced much reduced winter coverage, external and go into the warmest months tracking below the all time satellite minimum year of 2012.

But the Reading team says current ice extent is actually a poor guide to the scale of the eventual September low point.

A better correlation is with the fraction of the floes in May topped with melt ponds - and that metric suggests 2016 will not be a record year.

Ponding water accelerates melting by changing the reflectivity, or albedo, of white ice. The darker liquid absorbs more energy from the sun, promoting further melting and a larger fraction of standing water… and so on.

However, despite some remarkable conditions during the Arctic winter, this feedback process has not become a dominant factor in the right places and at the right time to really suppress sea ice in the coming weeks, contends Dr David Schroeder from the Nerc Centre for Polar Observation and Modelling (CPOM), external.

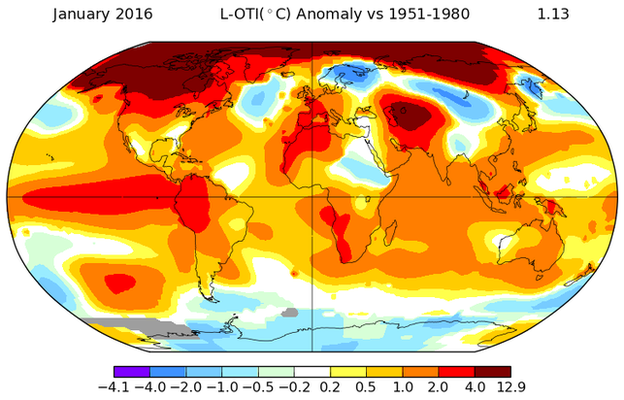

"2016 certainly looks to be an interesting year when you consider how low the extent has been through the winter, together with the strong sea-surface temperature anomalies. But the winter months are not when melt ponds start forming; this happens in the second half of May and the beginning of June. And during this period, although there were still positive anomalies in some locations, in the most important areas for melt pond fraction - such as in the east Siberian sea towards the central Arctic, for example - the temperatures were not very high."

The CPOM team has developed a model to forecast the evolution of melt ponds in the Arctic and has incorporated this into a more general climate sea-ice model. Its simulations suggest sea-ice extent for the end of this coming summer will be 4.5 (+/- 0.5) million square km. This number is for an average across the entire month of September - traditionally the period of minimum coverage.

It is slightly lower than last year (4.6 million sq km), but larger than the extraordinary September of 2012 when the floes retreated to just 3.6 million sq km.

Past forecasts have shown a high degree of skill. 2014 was pretty much spot on; 2015 came in a bit high but just on the edge of the error range.

"There is still an irreducible level of uncertainty associated with the weather conditions," said colleague Prof Daniel Feltham.

"We can't predict the atmospheric chaos that happens every year, and this places fundamental limits on how well we can predict the Arctic ice cover."

And to illustrate this point, 2012 was notable for an intense storm that blew up over the central Arctic Ocean during the early part of August. This gave the summer melt season an additional kick. Something similar could very easily happen again this year.

Walt Meier stands in an Arctic melt pond. The water is darker than the frozen ice

Reading's outlook has just been submitted to the Sea Ice Prediction Network (SIPN), external - a community forum for scientific and stakeholder groups that aim to compare and improve forecast tools. These groups all have their own perspectives, and the SIPN is expected to publish their individual forecasts online in the coming days.

Nasa's Dr Walter Meier, external is on the leadership team at SIPN.

He told BBC News: "I'd say we're at a stage where we're looking at people's different methods, looking at how they are performing, trying to understand why and how they get things right or wrong, and then hopefully working out how that might play into improving forecasts in the future.

"Making seasonal forecasts is a really hard problem because in the three-to-four months before September so much can happen that is weather-related: how much sun versus how much cloud; the temperature; the winds, and which way they're blowing. Do the winds blow to compress the ice together or blow to spread it out? Do they blow the ice into warmer water where it melts? This is really tough."

There is no doubt having better models for sea-ice forecasts would be useful to many sectors.

Shipping, tourism and oil industries - all are looking to exploit the opportunities that will emerge in an Arctic that is expected to become more open in a warming climate.

"For many stakeholders - they're not so much interested in the amount of ice in total; rather, they are interested in the amount of ice where they happen to be. So, it's the spatial variation that's of interest and that's something we're working on as well and hope to improve for the future," said Prof Feltham.

The far north had an anomalously warm winter

Jonathan.Amos-INTERNET@bbc.co.uk, external and follow me on Twitter: @BBCAmos, external

- Published17 June 2016

- Published26 October 2015

- Published24 September 2014