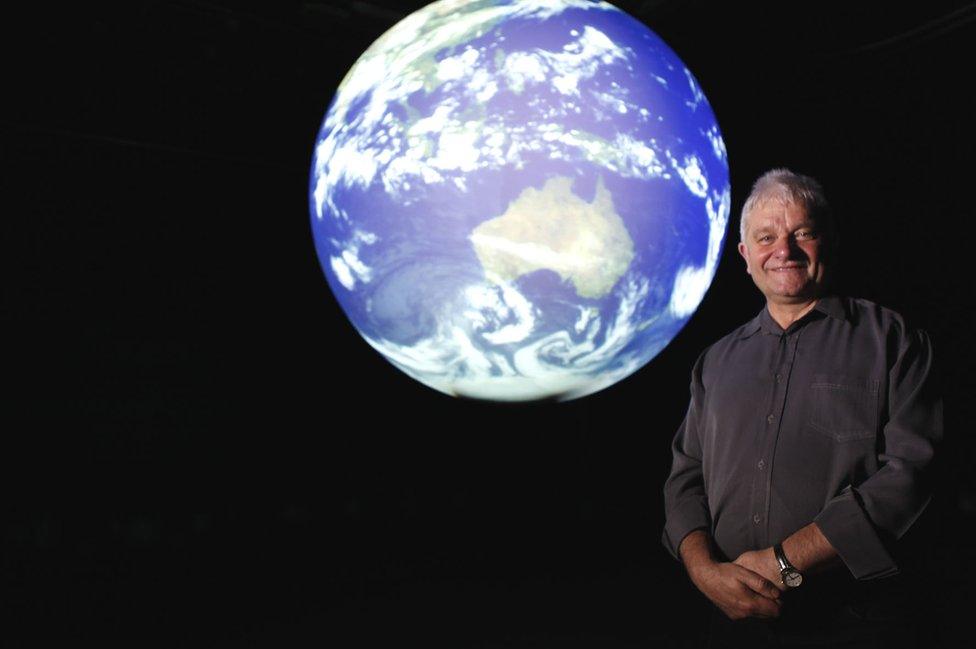

Paul Nurse: 'Research needs free movement to thrive'

- Published

A leading scientist has said UK science will suffer unless any post-Brexit agreement allows the free movement of people.

Prof Sir Paul Nurse said the country's research was facing its biggest threat in living memory.

He added that researchers had to have a big voice in negotiations with the EU.

But Leave campaigners say the UK should be able to negotiate a deal to continue to receive European funding and still curb overall immigration.

British science was one of the biggest winners from EU funding. And so it is among those that have most to lose.

UK universities receive 10% of their research funding from the EU, amounting to just over £1bn a year.

Full membership of the funding body requires participating countries to allow free movement of people.

Sir Paul Nurse said that exit from the EU jeopardised the world-class science for which the UK was known.

It risked damaging the economy and could lead to a loss of skills and talent.

"For science to thrive it must have access to the single market, and we do need free movement," he said.

"We could negotiate that outside the EU, which will probably end up costing more money and we would have little influence [in deciding research priorities].

"Or perhaps we should just reconsider this entire mess and see if there is something that can be done to reconsider this once the dust has settled."

The Nobel Prize-winning scientist added that even if the government agreed to reimburse the lost funds, which Leave campaigners had suggested might be possible, it would not replace the important international collaborations that British science needed to remain at the forefront of research.

Sir Paul Nurse says science will fail to thrive unless free movement is maintained

But Leave campaigners, such as Chris Leigh, from Scientists for Britain, say that there are several ways for the UK to negotiate a deal to continue to receive grants from the main European research programme, called Horizon 2020, and still stop free movement.

He said: "The first involves H2020 access for members of the European Free Trade Association, and, in the case of Norway, Switzerland and Iceland, this does appear to be linked to free movement.

"The second involves countries whose H2020 access is covered by the EU's Neighbourhood Policy, such as Israel, Tunisia, Georgia and Armenia, and this does not appear to require free movement.

"We also note that the current 'partial-access' status of Switzerland has opened up a third option, in that Swiss scientists have full access to Tier 1 H2020 activities, but participate in other aspects of H2020 (Tier 2/3) as a third country, but do so by funding their involvement directly.

"We would, however, urge our own government to recognise the importance of researcher mobility to science, and recommend that any future arrangements should ensure that scientists and students from around the world are still encouraged to visit, study and work in the UK."

British Universities employ about 30,000 scientists from EU countries.

The president of the Royal Society, which represents the UK's leading scientists, Sir Venkatraman Ramakrishnan, said many of them were now facing an uncertain future and so may choose to work elsewhere.

He said: "They are not just statistics; they are people worried about their job security.

"Government needs to act quickly to ensure that these researchers know that their jobs are safe.

"Universities have employed them because they are the brightest and the best, and other countries will know that and will come and get them."

Dr Noemie Bouhana, 40, a French researcher who arrived in the UK 18 years ago, lectures in crime science at UCL and leads an EU-funded project to track terrorism and the radicalisation of young men, involving collaborators across Europe.

She said: "Never in a million years would I get funding from central UK funds for this type of project, which is international, interdisciplinary and involves a mix of engineering and social sciences.

"I was shocked and disappointed when I heard the referendum result.

"At first, I did not believe it.

"I checked on several websites to see if it really was true.

"I then knew that I would not be in an EU country, and I hadn't realised how important that was to me, and I don't want to live in a non-EU country."

Mike Galsworthy, of pro-Remain campaign group Scientists for EU, said the country's current full relationship with the EU brought huge added value for UK science "from our strong policy voice on academic and single market standards through to leading roles on the EU multinational research programme".

He added: "We want to keep as much as possible, but, as the case of Switzerland showed us, negotiations will be complex.

"Much policy voice will be lost, and our renegotiated level of access will revolve around freedom of movement, the relationship with the single market, financial contributions and the interests of the remaining countries."

Follow Pallab on Twitter, external

- Published28 June 2016

- Published26 February 2016