Ancient barley DNA gives insight into crop development

- Published

Barley fields of 6,000 years ago may have looked very similar to those of today

An international group of scientists have analysed the DNA of 6,000 year old barley finding that it is remarkably similar to modern day varieties.

They say it could also hold the key to introducing successful genetic variation.

Due to the speed at which plants decompose, finding intact ancient plant DNA is extremely rare.

The preserved ancient barley was excavated near the Dead Sea, the journal Nature Genetics, external reports.

The arid environment conserved the biological integrity of the grains, the paper says.

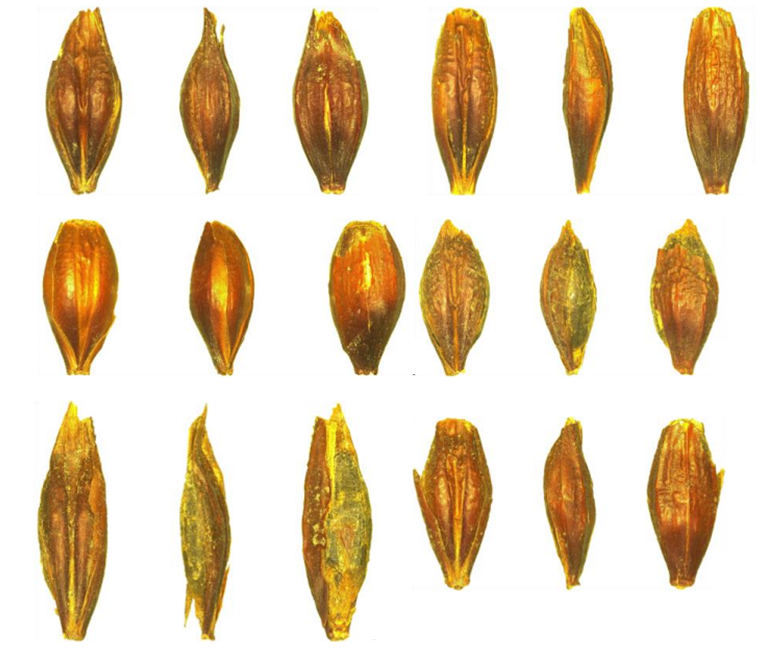

The team of researchers, consisting of archaeologists, specialists in ancient DNA analysis and experts in barley and crop genetics, recovered the ancient cultivated barley grains from a cave in an ancient fortress near the Dead Sea in Israel.

The preservation of the samples meant sufficient amounts of biological matter survived to enable isolation of genetic material and sequencing of the barley DNA.

Barley is one of the earliest farm crops, originally domesticated 10,000 years ago when the hunter-gatherers started farming. These ancient farmers started to grow wild plants and selected away traits that were unfavourable, very similar to modern day selective breeding.

The discovery of these seeds takes us closer in time to the original domestication of barley than ever before.

The DNA analysis showed that these 6,000 year old seeds were remarkably similar to modern day crops in the same region. Meaning that at the time they were harvested barley was already an advanced crop that had been heavily domesticated.

"These 6,000 year-old grains are time capsules, you have a genetic state that was frozen 6,000 years ago. This tells us barley 6,000 years ago was already a very advanced crop and clearly different from the wild barley," Dr Nils Stein of the IPK Plant Genetics institute in Germany told BBC News.

He added: "Already 6,000 years ago the barley fields may have looked very similar to barley that is grown today."

A hot and arid environment allowed biological preservation of the barley grains

Prof Monique Simmonds, deputy director of science at Kew Royal Botanic Gardens, said finding preserved samples of such an age is in itself impressive. She also praised the new DNA analysis techniques used.

Speaking to the BBC, she expressed the importance of the paper and said that this research should inspire further work with old collections and even motivate exploration in areas for other potential preserved ancient samples.

As well as providing a detailed insight into the archaeology and history of this ancient crop, the seeds could provide the key to ensuring successful reintroduction of genetic variation in modern day species.

Prof Nils Stein told the BBC: "Breeders are trying to increase genetic diversity; maybe the knowledge of these ancient seeds will allow us to spot better genotypes from gene banks and seed vaults."

"We could ask what are the variations of genes in the ancient samples, are specific alleles [genes] still present in modern day germplasm [seeds] - if they aren't why is this the case? Were they selected away on purpose or were they lost due to the domestication procedure, if this is the case there could still be value in these ancient genes," said Prof Stein.