Wild birds 'come when called' to help hunt honey

- Published

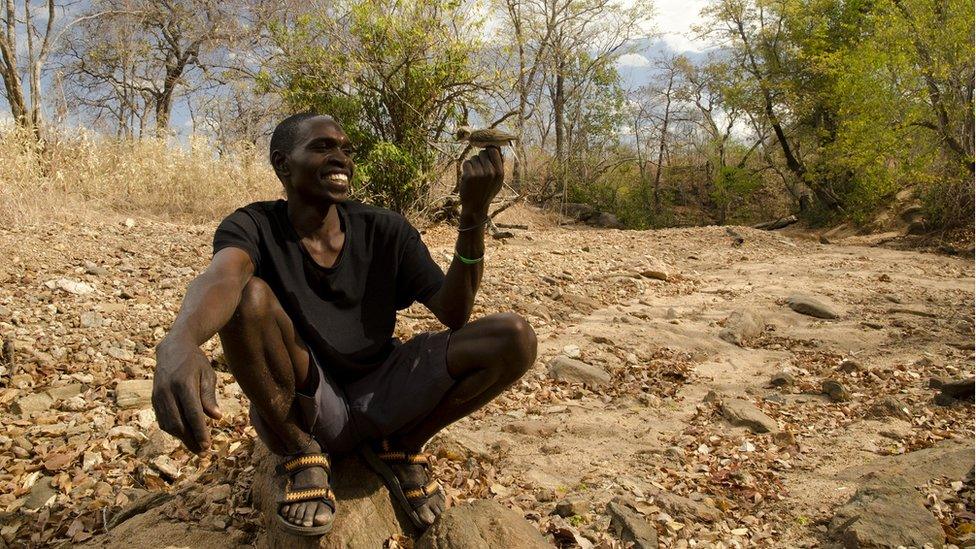

Honeyguides flutter from tree to tree ahead of the hunters

New findings suggest that the famous cooperation between honeyguide birds and human honey hunters in sub-Saharan Africa is a two-way conversation.

Honeyguides fly ahead of hunters and point out beehives which the hunters raid, leaving wax for the birds to eat.

The birds were already known to chirp at potential human hunting partners.

Now, a study in the journal Science, external reports that they are also listening out for a specific call made by their human collaborators.

Experiments conducted in the savannah of Mozambique showed that a successful bird-assisted hunt was much more likely in the presence of a distinctive, trilling shout that the Yao hunters of this region learn from their fathers.

"They told us that the reason they make this 'brrrr-hm' sound, when they're walking through the bush looking for bees' nests, is that it's the best way of attracting a honeyguide - and of maintaining a honeyguide's attention once it starts guiding you," said Dr Claire Spottiswoode, a researcher at the University of Cambridge, UK, and the University of Cape Town, South Africa, who led the study.

She and her colleagues wanted to test what contribution this sound actually made.

The greater honeyguide's proper Latin name is 'Indicator indicator'

"In particular, we wanted to distinguish whether honeyguides responded to the specific information content of the 'brrr-hm' call - which, from a honeyguide's point of view, effectively signals 'I'm looking for bees' nests' - or whether the call simply alerts honeyguides to the presence of humans in the environment."

To make that distinction, the team made recordings of the "brrrr-hm" call, as well as of general human vocal sounds such as the hunters shouting their own names, or the Yao word for "honey".

Then, Dr Spottiswoode accompanied two Yao honey hunters on 72 separate 15-minute walks through the Niassa National Reserve - a protected area the size of Denmark - playing these recordings on a speaker.

"This was great fun," she told BBC News. "We walked hundreds of kilometres through beautiful landscapes and occasionally bumped into elephants and buffalo and lions and so on. It's a really remarkable wilderness where humans and wildlife still coexist."

Beehives are often high in the trees

Sure enough, walks accompanied by the "brrrr-hm" recordings were much more likely to recruit a honeyguide (66% of the time, compared to 25% for the other vocal sounds).

The special call also trebled the overall chance of finding a beehive (a 54% success rate, up from 17% for the other sounds).

"What this suggests is that honeyguides are attaching meaning, and responding appropriately, to the signal that advertises people's willingness to cooperate.

"We already knew very well... that honeyguides communicate with humans, using special calls and behaviour to lead honey hunters to bees' nests. What our work has done is to complement those findings, by showing that humans communicate back to honeyguides too.

"It seems to be a two-way conversation between our own species and a wild animal, from which both partners benefit."

The hunters use smoke and axes to safely open the bees' nests

Prof Richard Wrangham, a biological anthropologist at Harvard University, said the new study greatly strengthened the idea that honeyguides had evolved to cooperate with humans in this way.

He said a previous explanation, that the teamwork originated with another species - such as honey badgers or baboons - and was then co-opted by humans, had fallen from favour because the birds had never been witnessed guiding these animals.

"[This study] shows just how tightly attuned they are to human sounds," Prof Wrangham told the BBC. "They're not just generally interested in weird noises - anything loud or unusual or whatever. They have been trained, as it were, to look for humans.

"That really supports the notion that this is an evolved, co-evolutionary relationship."

Follow Jonathan on Twitter, external