Last woolly mammoths 'died of thirst'

- Published

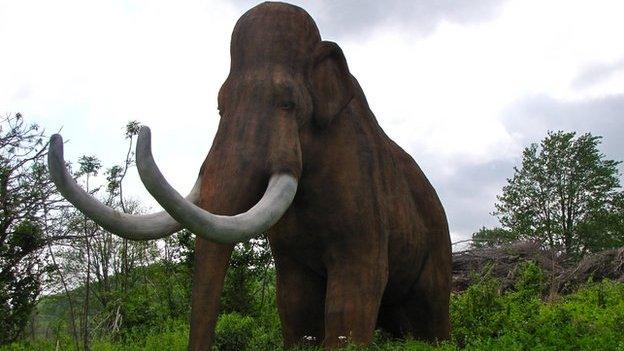

The mammoths on St Paul Island outlived their mainland cousins by thousands of years

One of the last known groups of woolly mammoths died out because of a lack of drinking water, scientists believe.

The Ice Age beasts were living on a remote island off the coast of Alaska, and scientists have dated their demise to about 5,600 years ago.

They believe that a warming climate caused lakes to become shallower, leaving the animals unable to quench their thirst.

Most of the world's woolly mammoths had died out by about 10,500 years ago.

Scientists believe that human hunting and environmental changes played a role in their extinction.

But the group living on St Paul Island, which is located in the Bering Sea, managed to cling on for another 5,000 years.

This study in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, external suggests that these animals faced a different threat from their mainland cousins.

As the Earth warmed up after the Ice Age, sea levels rose, causing the mammoths' island home to shrink in size.

This meant that some lakes were lost to the ocean, and as salt water flowed into the remaining reservoirs, freshwater diminished further.

The fur-covered giants were forced to share the ever-scarcer watering holes. But their over-use also caused a major problem.

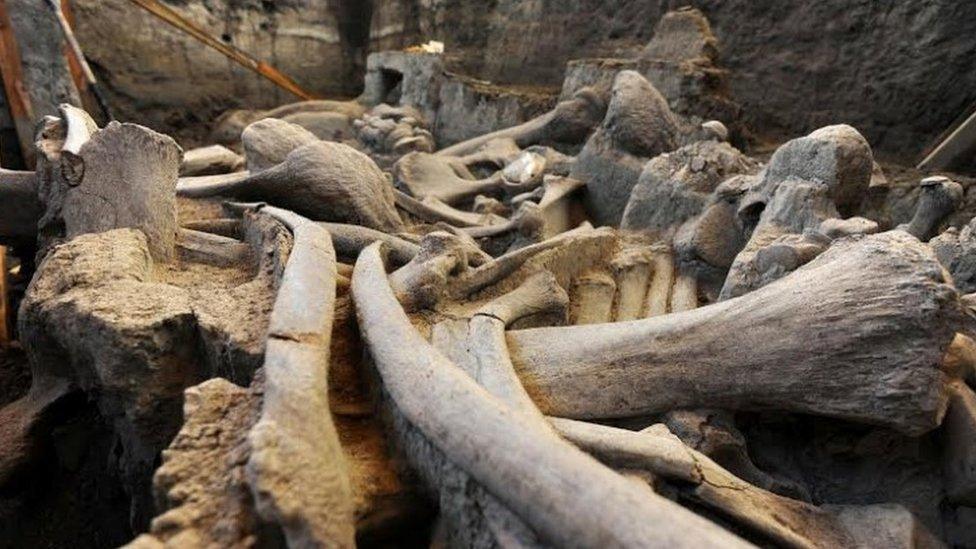

Ice cores were taken from St Paul Island

Lead author Prof Russell Graham, from Pennsylvania State University, said: "As the other lakes dried up, the animals congregated around the water holes.

"They were milling around, which would destroy the vegetation - we see this with modern elephants.

"And this allows for the erosion of sediments to go into the lake, which is creating less and less fresh water.

"The mammoths were contributing to their own demise."

He said that if there was not enough rain or melting snow to top the lakes up, the animals may have died very quickly.

"We do know modern elephants require between 70 and 200 litres of water daily," Prof Graham said.

"We assume mammoths did the same thing. It wouldn't have taken long if the water hole had dried up. If it had only dried up for a month, it could have been fatal."

The researchers say climate change happening today could have a similar impact on small islands, with a threat to freshwater putting both animals and humans at risk.

'Best understood extinction'

Commenting on the study, Love Dalen, professor in evolutionary genetics at the Swedish Museum of Natural History, said: "With this paper, the St Paul Island mammoth population likely represents the most well-described and best understood prehistoric extinction events.

"In a broader perspective, this study highlights that small populations are very sensitive to changes in the environment."

The very last surviving mammoths lived on Wrangel Island, in the Arctic Ocean. It is thought they died out 4,000 years ago.

Follow Rebecca on Twitter: @BBCMorelle, external

- Published25 June 2016

- Published23 April 2015

- Published3 October 2015