Brain-robot training triggers improvement in paralysis

- Published

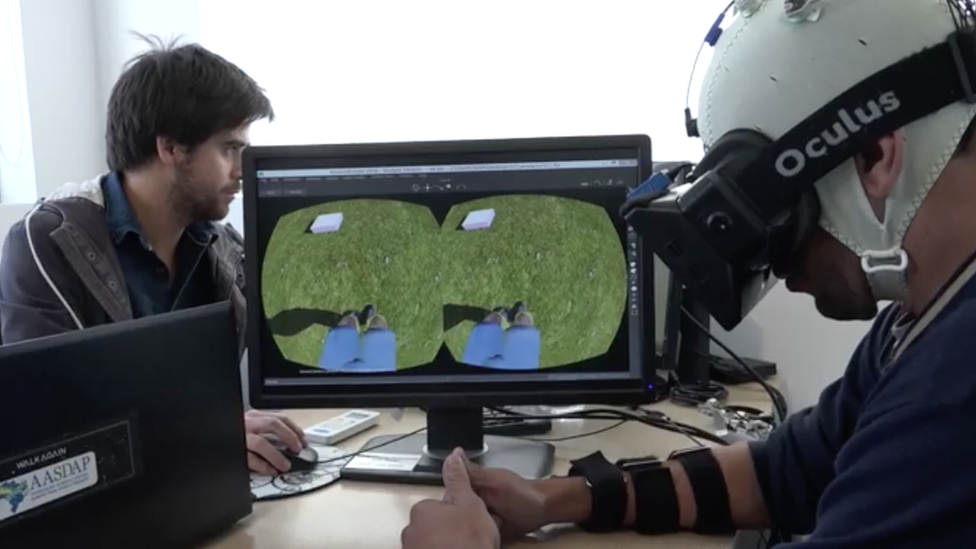

Before the program, these two patients were paralysed for 13 and 11 years (footage: AASDAP/Lente Viva Filmes)

In a surprise result, eight paraplegic people have regained some sensation and movement after a one-year training programme that was supposed to teach them to walk inside a robotic exoskeleton.

The regime included controlling the legs of a virtual avatar via a skull cap, and learning to manipulate the exoskeleton in the same way.

Researchers believe the treatment is reawakening the brain's control over surviving nerves in the spine.

The work appears in Scientific Reports, external.

The eight subjects had been paralysed for three to 13 years before the rehabilitation programme began. Chronic cases of paralysis such as these are the most resistant to treatment.

"If you're clinically diagnosed as having a complete lesion, if after 18 months you don't show any improvement, the chance of regaining any motor or sensory capability below the level of the lesion goes down to zero," said Miguel Nicolelis of Duke University in the US, who led the study at the AASDAP Neurorehabilitation Laboratory in Sâo Paulo, Brazil.

But when he and his team conducted neurological tests, every three months during the year of training, they saw improvements in the patients' muscle control - as well as in their sense of touch.

"If you touched them with a pin, or a brush… they would feel something that they didn't experience before," Prof Nicolelis told Science in Action on the BBC World Service.

"They also experienced a significant visceral improvement. This translated into better bowel and bladder functions - which are very critical for these patients."

Patients first learned to control the legs of an avatar in virtual reality

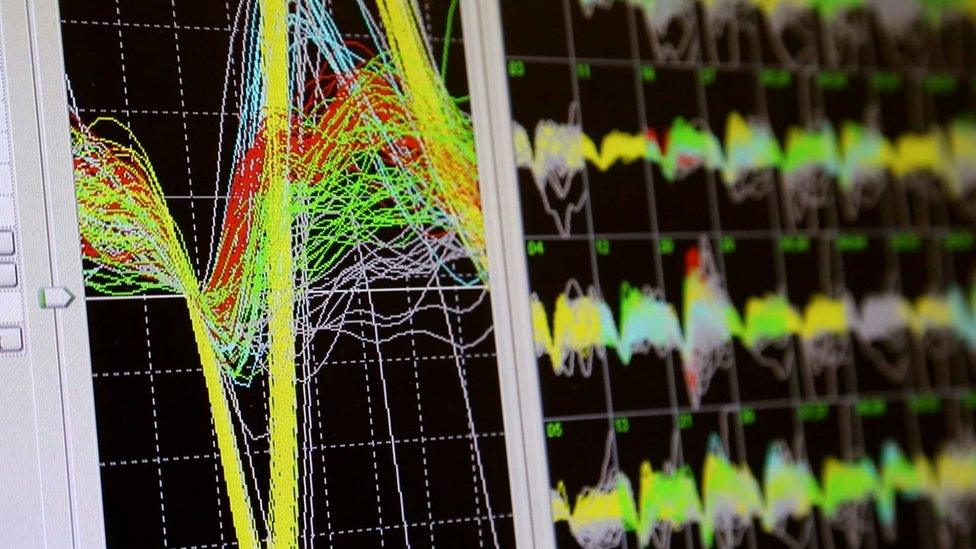

The system records brain waves from multiple electrodes in a skull cap

As well as intensive use of the non-invasive "brain-machine interface", the training incorporated two more established physiotherapy techniques based on assisted walking in a harness.

Other spinal repair experts said it was unclear which part of the training was responsible for the improvement, but that the degree of recovery was impressive compared with many other rehabilitation strategies.

"It clearly shows that there's a lot of untapped neuroplasticity potential within even a chronic spinal cord injury patient," said Dr Mark Bacon, chief executive and scientific director of the UK charity Spinal Research, external.

"But there's no control group - so you don't really know which combination of elements that they've applied… might be the major contributor."

Re-training the brain

With just eight patients and no comparison with other treatments, the study is not a clinical trial.

In fact, the researchers themselves were not expecting to see the patients improve in this way. When the study began, their aim was not to restore spinal cord function but to test whether paralysed people could learn to walk again with the aid of a brain-controlled exoskeleton.

This remarkable system, pioneered by Prof Nicolelis and featured at the 2014 World Cup opening ceremony, involves robotic leg supports that are controlled by brain waves, recorded using a non-invasive cap.

The process of earning to "drive" the exoskeleton began in a harness (footage: AASDAP/Lente Viva Filmes)

Information from electronic sensors on those robotic legs - such as when they touch the ground - is then fed back to the person, via vibrating pads worn in their sleeves.

"We use the arms of these patients as transducers, for the brain to perceive signals coming from the feet," said Prof Nicolelis.

"If you adjust these parameters just right, what you produce is some sort of phantom limb sensation. They patients have a feeling that they're walking by themselves."

He argues that this retraining of the brain is central to the patients' unexpected neurological progress, outside the exoskeleton.

Upgraded diagnosis

"In virtually every one of these patients, the brain had erased the notion of having legs. You're paralysed, you're not moving, the legs are not providing feedback signals.

"By using a brain-machine interface in a virtual environment, we were able to see this concept gradually re-emerging into the brain."

The team intended to use that re-awakened control to drive the robotic legs - but within 12 months they saw such improvement in basic clinical scores that four of the eight patients were upgraded to a diagnosis of only partial paraplegia.

"When I saw this, I couldn't believe it," said Prof Nicolelis.

The robotic system currently requires a large backpack to process all the signals

He believes the improvement arises from not only increased effort by the brain to control the legs, but a "rekindling" of the few remaining nerve connections in the patients' damaged spines.

As those few fibres start to send messages again, Prof Nicolelis speculated that there may even be some fresh sprouting of nerves.

But the only evidence his team has to work with is the patients' clinical improvement.

That improvement, he added, has continued since the 12 months covered by the paper, which were back in 2014. These more recent results are not yet published.

Dr Bacon from Spinal Research commented that although the results were difficult to interpret, they were promising.

"They've taken chronic, what would be considered neurologically stable patients - so the expectation would be that they wouldn't change with time - and they've recorded some sensory and motor changes in each of those patients, which is pretty impressive," he said.

Taking control

James Fawcett, of the Cambridge Centre for Brain Repair, also said the study was noteworthy.

"There's a lot of interest at the moment in how to make rehabilitation work better," he told the BBC. "Sometimes it works, and sometimes it doesn't."

In this case, the regime worked better than most walking-based rehabilitation efforts; but more work was required, Prof Fawcett said, to unpick exactly what had happened.

"Some patients do get better anyway. And when you treat them very intensively, there's a huge placebo effect.

"This is a basket of manipulations. But in a sense, they all fit together.

"It's an important step forward."

Follow Jonathan on Twitter, external

- Published13 April 2016

- Published4 March 2016

- Published21 October 2014

- Published1 June 2012

- Published20 May 2011