Dog vaccine offers hope in China’s fight against rabies

- Published

Cattle in northern China have shown an increasing incidence of rabies

Scientists in China have found that a rabies vaccine usually given to dogs can also protect livestock.

Rabies in domestic cattle and camels, infected by wild dog and fox bites, has been on the rise in north-west China.

Because there is no oral vaccine for wild animals in China, it is impossible to prevent this type of spread.

A vaccine for large domestic animals is what is needed, the researchers say, but the canine vaccine could provide a stop-gap measure.

Their findings are published in the journal PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases, external.

China has the second highest number of reported rabies cases in the world after India. The majority of infections come from contact with China's estimated 100 million-plus dogs.

Despite an increase in the dog population, human infections have been declining as a result of domestic dog vaccinations and education programmes.

But rabies is spreading to areas beyond the traditional rabies hotspot in the south, where five provinces account for 60% of human infections.

Rabies is typically transferred to humans or livestock by dog bites

Despite the government's commitment to eradicate rabies in China by 2025, numerous cases of livestock infections have been reported in previously unaffected areas, like the Xinjiang Autonomous Regions.

This follows a concerted, government-led campaign to develop areas that were traditionally only sparsely populated. Domestic vaccination in these regions is low and dog ownership is high, with as many as 70% of rural households keeping dogs.

Infection of livestock by wild dogs and foxes is an urgent concern to researcher Rong-Liang Hu and his team from the Academy of Military Medical Sciences in Changchun.

"It is likely that rabies will rapidly spread among non-vaccinated animals and spill over into humans," they write in the paper.

Herds infected by rabies can lead to huge economic losses for local farmers and risk transmission to humans, through contact with animals or consumption of infected meat.

Dr Hu's team collected tissue samples from infected cattle and camels in two areas of northern China and confirmed the virus had most likely been transferred from wild dogs and foxes.

They also conducted an experiment on 300 cattle and 330 camels during an outbreak in Ningxia Hui Autonomous Region and Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region.

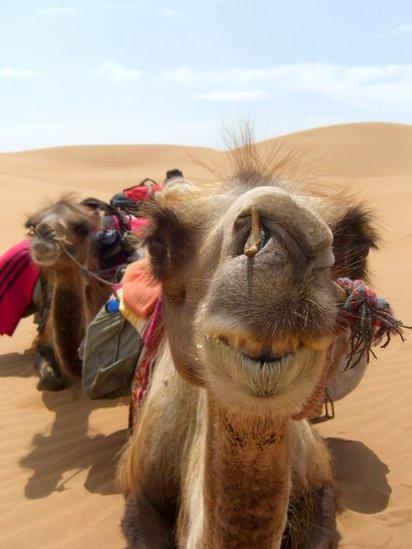

Camels and cattle could both get some protection from the canine vaccine

Dividing the animals into groups, they administered one, two or three doses of canine inactivated vaccine - the only type of vaccine currently available in China.

Comparing blood samples from before and after those vaccinations, the researchers found differences in the level of antibodies.

While one dose of the dog vaccine would fail to provide protection, animals receiving two doses were protected from infection for up to 12 months. Three doses were also effective but would be too expensive to administer on a large scale.

As long as China does not have an oral vaccine programme for wild animals - or a specific vaccine for livestock - this double-dose of the dog vaccine offers some hope to farmers.

China has a long history of rabies infection. More than 5,200 human deaths were being reported annually, external during the period 1987-89. Since then, however, improvements in vaccination programmes have led to a decrease over time, with fewer than 2,000 cases reported in 2011.

"In light of the history of rabies epidemics, we should recognize the serious situation of animal rabies control," Dr Hu and his colleagues wrote.

Rabies outbreaks are frequently followed by culls. One of the most notorious culls occurred in the city of Hanzhong in 2009 when more than 30,000 dogs were killed, many of them clubbed to death, in response to 13 human deaths.

Oral vaccines have been used successfully elsewhere in the world but these are not presently licensed for use in China.

- Published17 April 2015