Pollution particles 'get into brain'

- Published

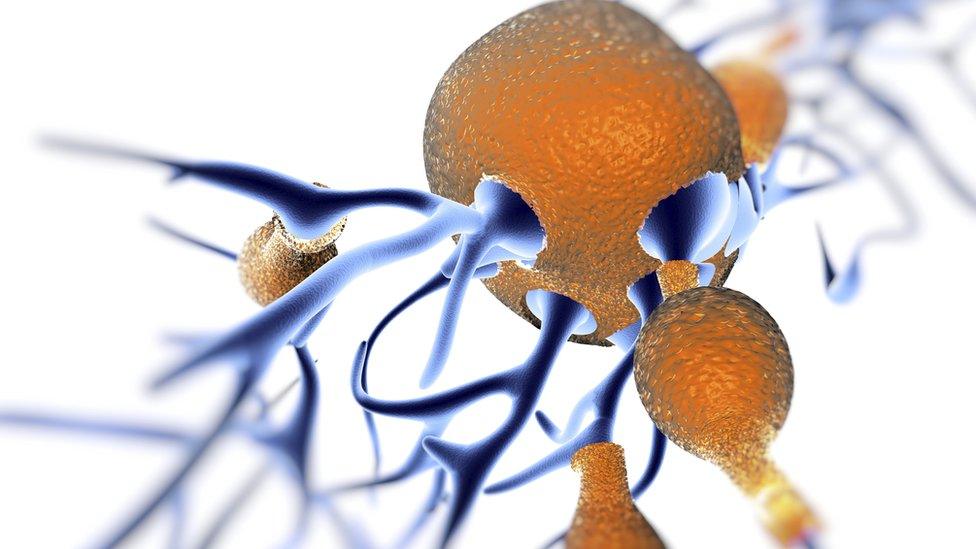

Tiny particles of pollution have been discovered inside samples of brain tissue, according to new research.

Suspected of toxicity, the particles of iron oxide could conceivably contribute to diseases like Alzheimer's - though evidence for this is lacking.

The finding - described as "dreadfully shocking" by the researchers - raises a host of new questions about the health risks of air pollution.

Many studies have focused on the impact of dirty air on the lungs and heart.

Now this new research provides the first evidence that minute particles of what is called magnetite, which can be derived from pollution, can find their way into the brain.

Earlier this year the World Health Organisation warned that air pollution was leading to as many as three million premature deaths every year.

Tracing origins

The estimate for the UK is that 50,000 people die every year with conditions linked to polluted air.

The research was led by scientists at Lancaster University and is published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS).

The team analysed samples of brain tissue from 37 people - 29 who had lived and died in Mexico City, a notorious pollution hotspot, and who were aged from 3 to 85.

The other 8 came from Manchester, were aged 62-92 and some had died with varying severities of neurodegenerative disease.

The lead author of the research paper, Prof Barbara Maher, has previously identified magnetite particles in samples of air gathered beside a busy road in Lancaster and outside a power station.

She suspected that similar particles may be found in the brain samples, and that is what happened.

"It's dreadfully shocking. When you study the tissue you see the particles distributed between the cells and when you do a magnetic extraction there are millions of particles, millions in a single gram of brain tissue - that's a million opportunities to do damage."

A link to Alzheimer's and other diseases is under investigation

Further study revealed that the particles have a distinctive shape which provides a crucial clue to their origin.

Magnetite can occur naturally in the brain in tiny quantities but the particles formed that way are distinctively jagged.

By contrast, the particles found in the study were not only far more numerous but also smooth and rounded - characteristics that can only be created in the high temperatures of a vehicle engine or braking systems.

Prof Maher said: "They are spherical shapes and they have little crystallites around their surfaces, and they occur with other metals like platinum which comes from catalytic converters.

"So for the first time we saw these pollution particles inside the human brain.

"It's a discovery finding. It's a whole new area to investigate to understand if these magnetite particles are causing or accelerating neurodegenerative disease."

For every one natural magnetite particle identified, the researchers found about 100 of the pollution-derived ones.

The results did not show a straightforward pattern. While the Manchester donors, especially those with neurodegenerative conditions, had elevated levels of magnetite, the same or higher levels were found in the Mexico City victims.

The highest level was found in a 32-year-old Mexican man who had been killed in a traffic accident.

Disease risk?

Dubbed "nanospheres", the particles are less than 200 nanometres in diameter - by comparison, a human hair is at least 50,000 nanometres thick.

While large particles of pollution such as soot can be trapped inside the nose, smaller types can enter the lungs and even smaller ones can cross into the bloodstream.

But nanoscale particles of magnetite are believed to be small enough to pass from the nose into the olfactory bulb and then via the nervous system into the frontal cortex of the brain.

Prof David Allsop, a specialist in Alzheimer's and other neurodegenerative diseases, is a co-author of the study and also at Lancaster University.

He said that pollution particles "could be an important risk factor" for these conditions.

"There is no absolutely proven link at the moment but there are lots of suggestive observations - other people have found these pollution particles in the middle of the plaques that accumulate in the brain in Alzheimer's disease so they could well be a contributor to plaque formation.

"These particles are made out of iron and iron is very reactive so it's almost certainly going to do some damage to the brain. It's involved in producing very reactive molecules called reaction oxygen species which produce oxidative damage and that's very well defined.

"We already know oxidative damage contributes to brain damage in Alzheimer's patients so if you've got iron in the brain it's very likely to do some damage. It can't be benign."

Other experts in the field are more cautious about a possible link.

Dr Clare Walton, research manager at the Alzheimer's Society, said there was no strong evidence that magnetite causes Alzheimer's disease or makes it worse.

"This study offers convincing evidence that magnetite from air pollution can get into the brain, but it doesn't tell us what effect this has on brain health or conditions such as Alzheimer's disease," she said.

"The causes of dementia are complex and so far there hasn't been enough research to say whether living in cities and polluted areas raises the risk of dementia. Further work in this area is important, but until we have more information people should not be unduly worried."

She said that in the meantime more practical ways of lowering the chances of developing dementia include regular exercise, eating a healthy diet and avoiding smoking.