DNA hints at earlier human exodus from Africa

- Published

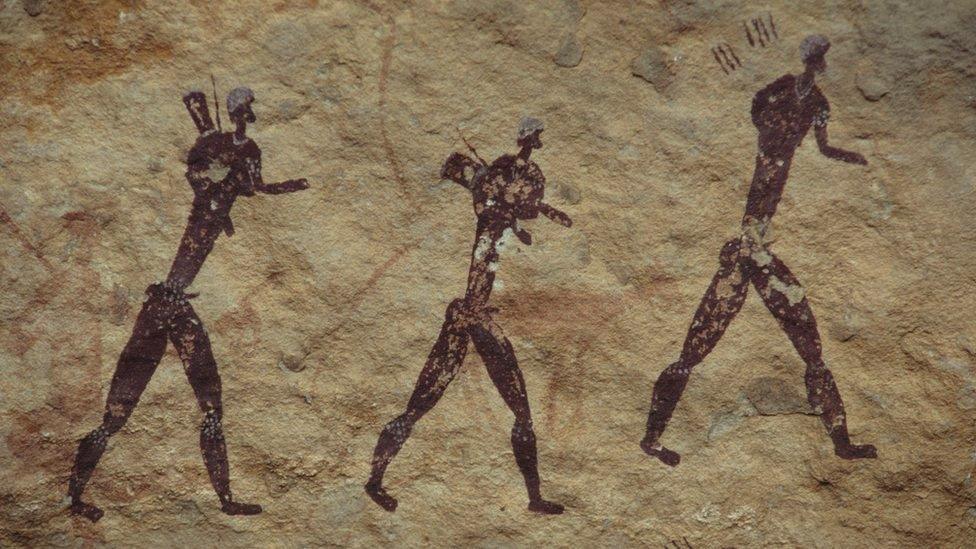

The early migrants were hunter-gatherers, like the people depicted in this much more recent rock art from South Africa

Hints of an early exodus of modern humans from Africa may have been detected in living humans.

People outside Africa overwhelmingly trace their descent to a group that left the continent 60,000 years ago.

Now, analysis of nearly 500 human genomes appears to have turned up the weak signal of an earlier migration.

But the results suggest this early wave of Homo sapiens all but vanished, so it does not drastically alter prevailing theories of our origins.

And two separate studies in the academic journal Nature failed to find the signature of this migration.

But Luca Pagani, Mait Metspalu and colleagues describe hints of this pioneer group in their analysis of DNA, external in people from the Oceanian nation of Papua New Guinea.

After evolving in Africa 200,000 years ago, modern humans are thought to have crossed through Egypt into the Arabian Peninsula some 60,000 years ago.

Until now, genetic evidence has shown that today's non-Africans could trace their origins to this fateful dispersal.

Yet we had known for some time that groups of modern humans made forays outside their "homeland" before 60,000 years ago.

Fossilised remains found at the Qafzeh and Es Skhul caves in Israel had been dated to between 120,000 and 90,000 years ago.

Then in 2015, scientists working in Daoxian, south China, reported the discovery of modern human teeth, external dating to at least 80,000 years ago.

An additional piece of evidence recently came from traces of Homo sapiens DNA, external in a female Neanderthal from Siberia's Altai mountains. The analysis suggested that modern humans and Neanderthals had begun mixing around 100,000 years ago - presumably outside Africa.

The faint signature of an earlier out of Africa migration may be found in people from Papua New Guinea

In order to reconcile this evidence with the genetic data from living populations, the prevailing view advanced by scientists was of a wave of pioneer settlement that ended in extinction.

But the latest results suggest some descendents of these trailblazers survived long enough to get swept up in the later, ultimately more successful migration that led to the settling of Oceania.

"The first instance when we thought we were seeing something was when we used a technique called MSMC, which allows you to look at split times of populations," said co-author Dr Mait Metspalu, director of the Estonian Biocentre in Tartu, external, told BBC News.

His colleague and first author Dr Luca Pagani, also from the Estonian Biocentre, added: "All the other Eurasians we had were very homogenous in their split times from Africans.

"This suggests most Eurasians diverged from Africans in a single event... about 75,000 years ago, while the [Papua New Guinea] split was more ancient - about 90,000 years ago. So we thought there must be something going on."

It was already known that Papua New Guineans, along with other populations from Oceania and Asia, derive a few per cent of their ancestry from Denisovans, an enigmatic sister group to the Neanderthals.

The researchers tried to remove this component, but were left with a third chunk of the genome which was different from the Denisovan segment and the overwhelming majority which represents the main out of Africa migration 60,000 years ago.

Fossil evidence from Israel, like this individual from Qafzeh cave, suggests modern humans were already living outside Africa at least 90,000 years ago

Teeth from Daoxian suggest Homo sapiens had reached southern China by at least 80,000 years ago

"This third component had intermediate properties which we concluded must have originated as an independent expansion out of Africa about 120,000 years ago," Dr Pagani told BBC News.

"We believe this makes up at least 2% of the genome of modern [Papua New Guineans]."

In a separate paper, external in the same edition of Nature, Prof David Reich and Swapan Mallick, both from Harvard Medical School, along with colleagues analysed 300 genomes from 142 different populations around the world.

They found evidence of early splits between populations within Africa, along with a single dispersal that gave rise to non-African populations.

But they found no signs of substantial ancestry from an early African exodus in Papua New Guineans and other related populations such as indigenous Australians. They conclude that, if the genetic legacy of such a migration survives in these populations, it can't comprise more than a few per cent of their genomes.

A similar conclusion is reached in a third study, external on the genomes of indigenous Australian by the University of Copenhagen's Eske Willerslev and Anna-Sapfo Malaspinas, along with colleagues.

David Reich told BBC News: "In our paper, we exclude more than about 2% ancestry in Australians, Papuans, and New Guineans from an early dispersal population, and our best estimate is 0%.

"I am a bit concerned that poorly modelled features of the methods used by Pagani and colleagues may have contributed to a false-positive signal of early dispersal ancestry in them. However, an alternative possibility is that the truth is around 2%, and this might just be consistent with all three studies."

Commenting on the Reich Lab study, Dr Metspalu told BBC News: "They do not detect an early Out of Africa, but they also do not reject it as long as it is just a few per cent in modern humans."

Dr Pagani added: "All three papers all reach the same conclusions. That in Eurasians and also [Papua New Guineans] - the majority of their genomes come from the same major migration."

Prof Chris Stringer, from London's Natural History Museum, external, who was not involved with the genomic studies, commented: "The papers led by Mallick and by Malaspinas favour a single exit from Africa less than 80,000 years ago giving rise to all extant non-Africans, while that led by Pagani favours an additional and earlier exit more than 100,000 years ago, traces of which they claim can still be found in Australasians.

"Unfortunately, the signs of past interbreeding with a Denisovan-like archaic population which are found at a level of about 4% in extant Australasians, according to the Malaspinas paper, complicate interpretations, as well as the possibility that there may have been yet other ancient interbreedings which are so far poorly understood."

Follow Paul on Twitter., external