Cheetah is now 'running for its very survival'

- Published

Endangered species like the cheetah are being used as pets, as David Shukman reports

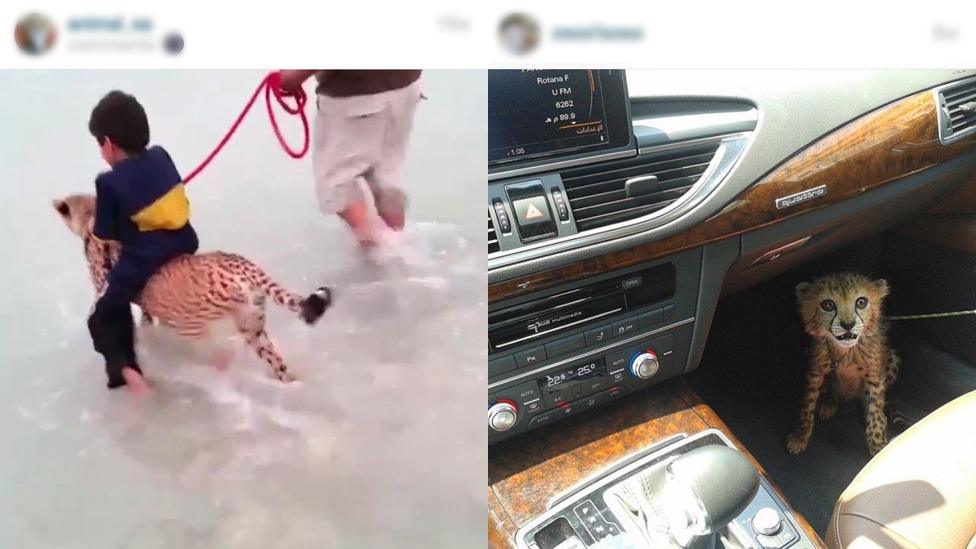

Pitiful scenes of cheetah cubs lying emaciated and bewildered highlight one of the cruellest but least-publicised examples of illegal wildlife trafficking.

Baby cheetahs are so prized as exotic pets that entire litters are seized from their mothers when they may only be four to six weeks old.

Each tiny animal can fetch as much as $10,000 on the black market and end up being paraded on social media by wealthy buyers in Gulf states.

But the trade exacts a terrible toll on a species that claims a superlative status as the fastest land animal on the planet but which now faces a serious threat to its survival.

The lucky ones: These young cheetahs were rescued

According to the Cheetah Conservation Fund, some 1,200 cheetah cubs are known to have been trafficked out of Africa over the past 10 years but a shocking 85% of them died during the journey.

Dr Laurie Marker, the trust's director, describes the horrific conditions involved in shipping the animals from their habitats in northern Kenya, Somaliland and Ethiopia by land and sea to the Arabian Gulf.

"They're probably just thrown into a crate, living in their own faeces, travelling for days without proper food, and many of them end up dead on arrival at wherever that place would be, and maybe one or two living out of a pile that are dead."

And those that do make it into the hands of new owners usually die rapidly because they are denied the chance to exercise and are given an inadequate diet.

The animal is used to living in huge home ranges of 800 sq km

Dr Marker says that they're often kept in "chicken coop-sized pens" which are far too small for them.

"And this is an animal that is the fastest land animal that is used to living in huge home ranges of 800 sq km. Most of those cheetahs don't make it over a two-year period of time in captivity."

With the total of adult cheetahs living in the wild now numbering less than 7,000, the concern is that seizures of an estimated 200-300 a year could drive some of the remaining populations, which are already diminished, to extinction.

The poaching comes on top of the long-running destruction of the cheetahs' habitats. The animals tend not to thrive in the confines of national parks where other predators dominate, so they live outside protected areas and are more exposed to conflict with people.

The threat to the cheetah will be raised at the CITES COP17 conference being held in Johannesburg over the next fortnight.

"You have the car and the boat but nothing tops having an exotic pet"

One criticism of the conservation movement is that it has recently been doing a better job highlighting the plight of the giants of African wildlife, the elephants and the rhinos, compared with other iconic species whose existence is equally at risk.

As a vet working in Kuwait, Jill Mullen saw for herself how easily cheetah cubs were imported despite the existence of controls under the CITES convention.

Now back in the UK, she told me how her surgery would see as many as six cubs in a single day. All of them would be suffering from dehydration, malnutrition and a common virus known as panleukopenia against which the cubs have no immunity.

Usually, only one of the six would survive.

"I would stand on the soapbox to explain to the owners why it was wrong to have these animals as pets, that they're endangered in the wild, and are not designed to be kept in living rooms and in villas.

"But in the end I had to swallow the feeling that everything was wrong because that was my job."

Ms Mullen found that most owners did not know about the CITES restrictions or care about them.

Endangered species like the cheetah are being used as pets, as David Shukman reports

"You have the car and the boat but nothing tops having an exotic pet and, if they can buy it, it doesn't matter about the legality."

During her time in Kuwait, there was an attempt by the authorities to clamp down, and vets like her were banned from handling cheetahs and other endangered animals. But she believes this drove the trade underground.

On the agenda in Johannesburg is a quest to raise awareness in buyer countries of the dangers the trade poses to the cheetah.

One idea is to persuade internet platforms to join the fight - many carry social media pictures taken by cheetah owners showing off their animals. Others allow dealers to offer cheetah cubs for sale.

Another initiative is to draw up plans for how to handle cheetahs if they are confiscated - if the authorities do get tough, large numbers may suddenly need to be housed.

Already when cheetahs become too big, or their owners find that they cannot care for them, the animals are released into the streets and found dead or weakened.

But there is a sense that time is not on the side of a species whose very fame may be the cause of its demise.

As Dr Marker puts it, "the cheetah is running the most important race of its life, and that's for its very survival and its survival is in human hands".