Sweet potato Vitamin A research wins World Food Prize

- Published

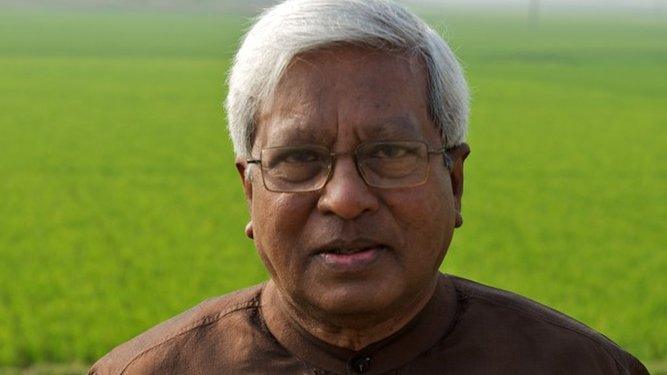

The orange-fleshed sweet potato provide a valuable source of calories and nutrients for millions of people

Four scientists have been awarded the 2016 World Food Prize for enriching sweet potatoes, which resulted in health benefits for millions of people.

They won the prize for the single most successful example of biofortification, resulting in Vitamin A-boosted crops.

Since 1986, the World Food Prize aims to recognise efforts to increase the quality and quantity of available food.

The researchers received their US $250,000 (£203,000) prize at a ceremony in Iowa, US, on Thursday.

Three of the 2016 laureates - Drs Maria Andrade, Robert Mwanga and Jan Low from the CGIAR International Potato Center - have been recognised for their work developing the vitamin-enriched orange-fleshed sweet potato (OFSP).

The fourth winner, Dr Howard Bouis who founded HarvestPlus at the International Food Policy Research Institute, has been honoured for his work over 25 years to ensure biofortification was developed into an international plant breeding strategy across more than 40 countries.

'Science matters'

Announcing this year's winners, USAID administrator Gayle Smith said: "These four extraordinary World Food Prize Laureates have proven that science matters, and that when matched with dedication, it can change people's lives."

Vitamin A deficiency (VAD) is considered to be one of the most harmful forms of malnutrition in the developing world. It can cause blindness, limits growth, weakens immunity and increases mortality.

The condition affects more than 140 million pre-school children in 118 nations, and more than seven million pregnant women. It is said to be the leading cause of child blindness in developing countries.

The World Health Organization describes biofortification as the process "by which the nutritional quality of food crops is improved through agronomic practices, conventional plant breeding, or modern biotechnology".

It observes: "Biofortification may therefore present a way to reach populations where supplementation and conventional fortification activities may be difficult to implement."

Growing the biofortified crops ensure people get the vital nutrients into people's daily diets

The World Food Prize ceremony will take place during the the Borlaug Dialogue International Symposium, a three-day gathering in Des Moines, Iowa, named after Nobel Peace Prize winner Norman Borlaug.

Dr Borlaug, often called the father of the Green Revolution, established the World Food Prize 30 years ago to recognise "exceptionally significant" achievements by individuals. In 1970, Dr Borlaug won the Nobel Peace Prize in recognition of his contribution to world peace through his work to increase global food supplies.

A report published at the Borlaug Dialogue warned that growth in global agricultural productivity (GAP), for the third year in a row, was not advancing at the rate required to meet future demand for food.

The Global Harvest Initiative's (GHI) seventh annual GAP report warned that unless this emerging trend was reversed, the "world may not be able to sustainably provide the food, feed, fibre and biofuels needed for a booming global population".

According to the GHI, GAP needed to increase by at least 1.75% each year. However, its latest figures showed that the current rate was only 1.73%.

The authors observed that productive techniques and technology were "essential for producers of all scales as climate change and extreme weather events threaten the sustainability of agricultural value chains".

GHI executive director Dr Margaret Zeigler said the agriculture sector had the potential to be a "climate change mitigation powerhouse".

She added: "Private sector investment, investment and scale will help more farmers, ranchers and forest managers access tools and practices that contribute to a low-carbon agricultural system."

Conflict and hunger

Another factor that was affecting regions' ability to produce food was conflict and civil unrest. One of the topics at the 2016 Borlaug Dialogue is the issue of national security and food security in affected regions.

Kenneth Quinn, former US ambassador to Cambodia and president of the World Food Prize Foundation, told BBC News:

"Just as factors like climate volatility, water scarcity, inferior infrastructure and post harvest loss can affect farmers' yields and food reaching urban centres, so too can military conflict and political instability disrupt markets, impede distribution of new technologies and innovations to farmers and halt new rural investment."

He added: "Throughout my diplomatic career, I have seen the incredible transformative power of agricultural development to undercut the allure and recruiting ability of radical terrorist organisations in remote areas."

Productive agricultural systems deliver both social and economic benefits for families and communities

One scientist who had first-hand experience of the impact of war on agricultural research was Mohmoud Solh, director-general of the International Center for Agricultural Research in Dry Areas (Icarda).

He explained how the Syrian civil war ripping the country apart had forced his team of researchers to leave the country.

Also left behind was Icarda's seed bank in Aleppo, which contained a vast array of samples from many species of staple food crops' wild relatives, which may hold the genes required to produce future generations of climate-proof crops. Most of which were collected from the "fertile crescent", which is widely considered to be the birthplace of modern agriculture.

However, Dr Solh told BBC News that the team was now continuing its work in Morocco and Lebanon.

But he added that he would have a clear message in his speech to delegates at the Borlaug Dialogue.

"You can see the importance of supporting before they reach that stage, the point I want to say is that the upheaval is not just political - it is because of poverty, lack of jobs and food insecurity.

"Many of the migrants are not just because they are leaving security hotspots, it is because there are few or no opportunities for them or their families.

Dr Solh added: "Sustainable development is needed. Proper investment is needed to ensure people have jobs and a future, otherwise the problems will mushroom."

On Tuesday, the publishers of the Global Hunger Index warned that the international community was not making enough progress to end world hunger by 2030, which is one of the UN Sustainable Development Goals.

"The world has made progress in the fight against hunger but it has so far been too slow," observed Rose Caldwell, executive director of humanitarian organisation Concern Worldwide UK.

"Hunger continues to waste lives and limit potential - we need urgent action from the global community to wipe it out for good."

The latest Index in the ongoing series - produced by Concern Worldwide, the International Food Policy Research Institute and German NGO Welthungerhilfe - suggested that if the decline in global hunger rates continued to decline at the rates recorded since the early 1990 then at least 45 nations, including Pakistan, Zimbabwe and Afghanistan, would still have "moderate" to "alarming" hunger scores in 2030.

Follow Mark on Twitter., external

- Published2 July 2015

- Published17 October 2015

- Published11 October 2012