Maths becomes biology's magic number

- Published

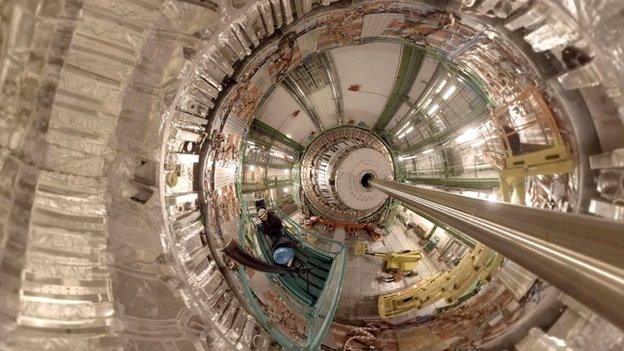

Andrea Sottoriva used to work analysing the results experiments conducted with the Large Hadron Collider

"If you want a career in medicine these days you're better off studying mathematics or computing than biology."

This pithy aside was delivered by Sir Rory Collins, the head of clinical trials at Oxford University, in the middle of a discussion about the pros and cons of statins.

It is a nice one-liner, but I didn't think much more about it until a few days later, when I found myself sitting in a press conference to mark the launch of a new initiative on cancer.

Rubbing shoulders on the panel with the director of the Institute of Cancer Research, Professor Paul Workman, was a scientist I didn't recognise, but it soon became clear this was exactly what Sir Rory had had in mind.

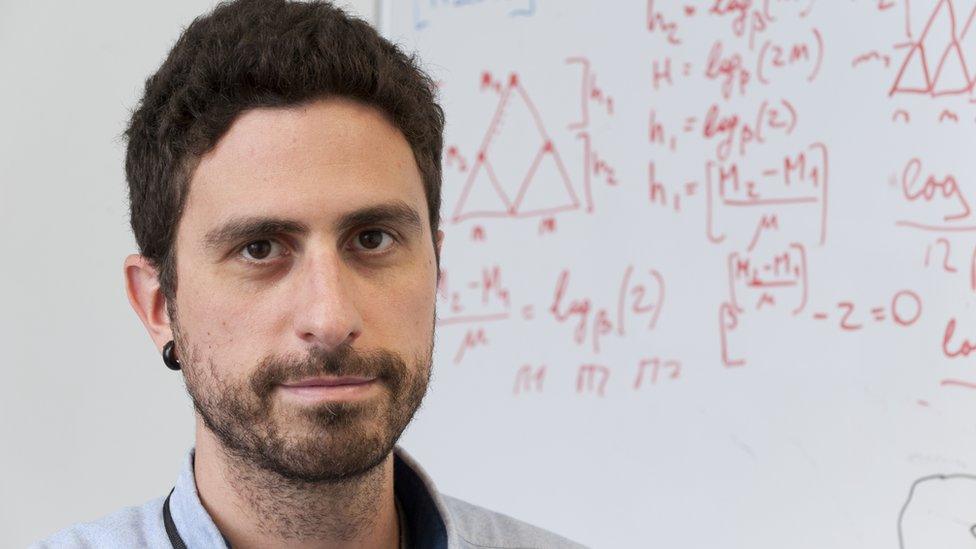

Dr Andrea Sottoriva is an astrophysicist. He has spent much of his career searching for Neutrinos - the elusive sub-atomic particles created by the fusion of elements in stars like our sun - at the bottom of the ocean, and analysing the results of atom smashing experiments with the Large Hadron Collider at Cern in Geneva.

"My background is in computer science, particularly as it applies to particle physics," he told me when we met at the ICR's laboratories in Sutton

New era

So why cancer? The answer can be summed up in two words: big data. What Dr Sottoriva brings to the fight against cancer is the expertise in mathematical modelling needed to mine the vast treasure trove of data the information revolution has brought to medicine.

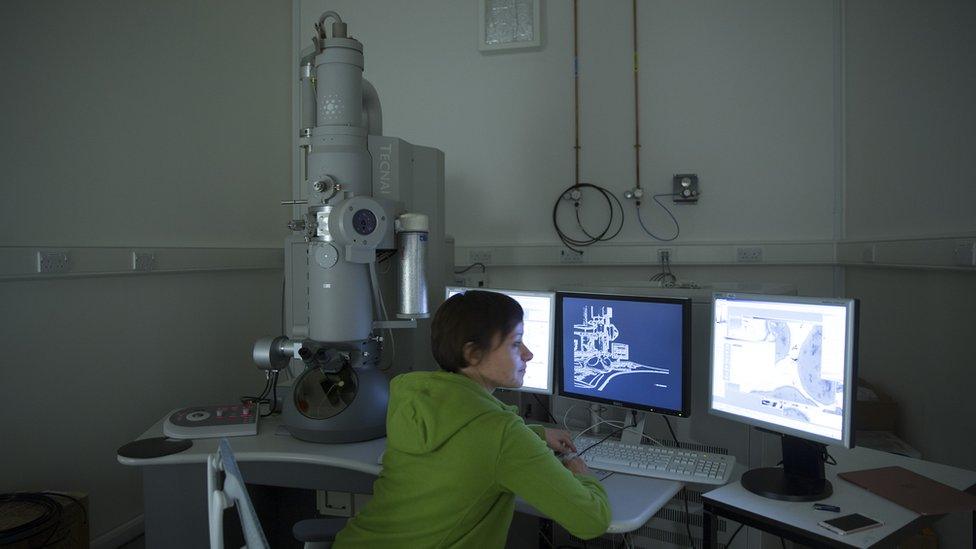

Biomedical equipment at the Francis Crick Institute in London

"The exciting thing is that we can apply all the new analytical techniques we've developed in physics to biology," he says.

"So we have all these new quantitative technologies that allow us to process an enormous amount of data, and all of a sudden we can start to apply that to implement the paradigm of physics in biology."

Of course, applying maths to solve biological problems is not entirely new. But it is only now, according to Sir Rory Collins, that the big data revolution is transforming medical science and ushering in a new era of bioinformatics.

"The big data era we're in provides extraordinary opportunities to understand the determinants of a range of different health conditions," says Sir Rory.

"The availability of data is unsurpassed, the ways of manipulating that data are also unsurpassed and so are the opportunities to work out what's going on and how to avoid disease."

'Datageddon' warning

But there's a problem. The vast data sets that give bioinformatics its power are also its Achilles heel.

The Professor of Science and Society at Arizona State University, Daniel Sarewitz, warns of "datageddon" - over-enthusiastic researchers risking being set adrift on a sea of irrelevant information.

Fighting cancer could be like playing chess, suggests Andrea Sottoriva

"If mouse models are like looking for your keys under the streetlamp, big data is like looking for your keys all over the world just because you can," says Professor Sarewitz.

The epidemiologist Professor Liam Smeeth agrees. If researchers aren't very disciplined about what they're looking for, he argues, they can quickly disappear down rabbit holes and blind alleys.

"The analogy is like someone firing an arrow at a wall," he says. "They fire at a big blank wall and then go up and draw a target around the arrow and say we've hit bullseye.

"What you need is to be doing is precise science and to be firing at a pre-specified target."

The answer, according to Dr Sottoriva, may be to approach big data like a grandmaster approaches chess.

To use mathematical modelling to understand and decode the rules of the game cancer is playing.

"What grandmasters do is to predict the moves of the opponent," he says. "If we can decode the complexity and make predictions about what cancer will do three, four moves ahead, then we can develop really effective treatments based on a solid mathematical framework."

- Published7 February 2016

- Published13 February 2015

- Published11 March 2016