World wildlife populations 'fall by 58% in 40 years'

- Published

This report estimates that wildlife populations have declined by nearly 60% since 1970

Global wildlife populations have fallen by 58% since 1970, a report says.

The Living Planet assessment, by the Zoological Society of London (ZSL) and WWF, suggests that if the trend continues that decline could reach two-thirds among vertebrates by 2020.

The figures suggest that animals living in lakes, rivers and wetlands are suffering the biggest losses.

Human activity, including habitat loss, wildlife trade, pollution and climate change contributed to the declines.

Dr Mike Barrett. head of science and policy at WWF, said: "It's pretty clear under 'business as usual' we will see continued declines in these wildlife populations. But I think now we've reached a point where there isn't really any excuse to let this carry on.

"We know what the causes are and we know the scale of the impact that humans are having on nature and on wildlife populations - it really is now down to us to act."

However the methodology of the report has been criticised.

The report looked at data collected on 3,700 species of vertebrates over the last 40 years

The Living Planet Report is published every two years and aims to provide an assessment of the state of the world's wildlife.

This analysis looked at 3,700 different species of birds, fish, mammals, amphibians and reptiles - about 6% of the total number of vertebrate species in the world.

The team collected data from peer-reviewed studies, government statistics and surveys collated by conservation groups and NGOs.

Any species with population data going back to 1970, with two or more time points (to show trends) was included in the study.

The researchers then analysed how the population sizes had changed over time.

Some of this information was weighted to take into account the groups of animals that had a great deal of data (there are many records on Arctic and near Arctic birds, for example) or very little data (tropical amphibians, for example). The report authors said this was to make sure a surplus of information about declines in some animals did not skew the overall picture.

The last report, published in 2014, estimated that the world's wildlife populations had halved over the last 40 years.

This assessment suggests that the trend has continued: since 1970, populations have declined by an average of 58%.

Dr Barrett said some groups of animals had fared worse than others.

"We do see particularly strong declines in the freshwater environment - for freshwater species alone, the decline stands at 81% since 1970. This is related to the way water is used and taken out of fresh water systems, and also the fragmentation of freshwater systems through dam building, for example."

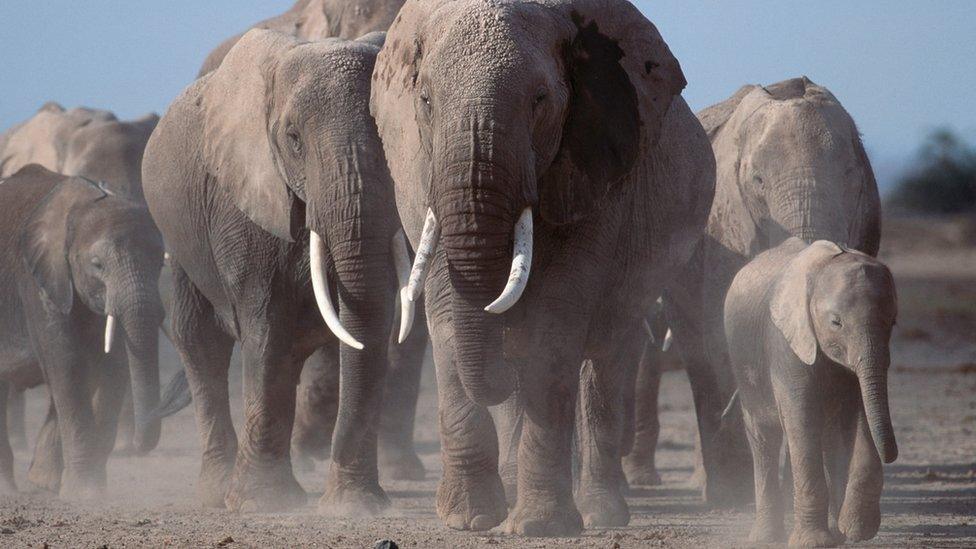

African elephants numbers have fallen dramatically as poaching has increased

It also highlighted other species, such as African elephants , which have suffered huge declines in recent years with the increase in poaching, and sharks, which are threatened by overfishing.

The researchers conclude that vertebrate populations are declining by an average of 2% each year, and warn that if nothing is done, wildlife populations could fall by 67% (below 1970 levels) by the end of the decade.

Dr Robin Freeman, head of ZSL's Indicators & Assessments Unit, said: "But that's assuming things continue as we expect. If pressures - overexploitation, illegal wildlife trade, for example - increase or worsen, then that trend may be worse.

"But one of the things I think is most important about these stats, these trends are declines in the number of animals in wildlife populations - they are not extinctions. By and large they are not vanishing, and that presents us with an opportunity to do something about it."

There are still many gaps in our knowledge of the world's vertebrates

However, Living Planet reports have drawn some criticisms.

Stuart Pimm, professor of conservation ecology at Duke University in the United States, said that while wildlife was in decline, there were too many gaps in the data to boil population loss down to a single figure.

"There are some numbers [in the report] that are sensible, but there are some numbers that are very, very sketchy," he told BBC News.

"For example, if you look at where the data comes from, not surprisingly, it is massively skewed towards western Europe.

"When you go elsewhere, not only do the data become far fewer, but in practice they become much, much sketchier... there is almost nothing from South America, from tropical Africa, there is not much from the tropics, period. Any time you are trying to mix stuff like that, it is is very very hard to know what the numbers mean.

"They're trying to pull this stuff in a blender and spew out a single number.... It's flawed."

But Dr Freeman said the team had taken the best data possible from around the world.

"It's completely true that in some regions and in some groups, like tropical amphibians for example, we do have a lack of data. But that's because there is a lack of data.

"We're confident that the method we are using is the best method to present an overall estimate of population decline.

"It's entirely possible that species that aren't being monitored as effectively may be doing much worse - but I'd be very surprised if they were doing much better than we observed. "

Follow Rebecca on Twitter: @BBCMorelle, external

- Published30 September 2014

- Published30 April 2015

- Published23 September 2016

- Published28 September 2016