Gut instinct drives battery boost

- Published

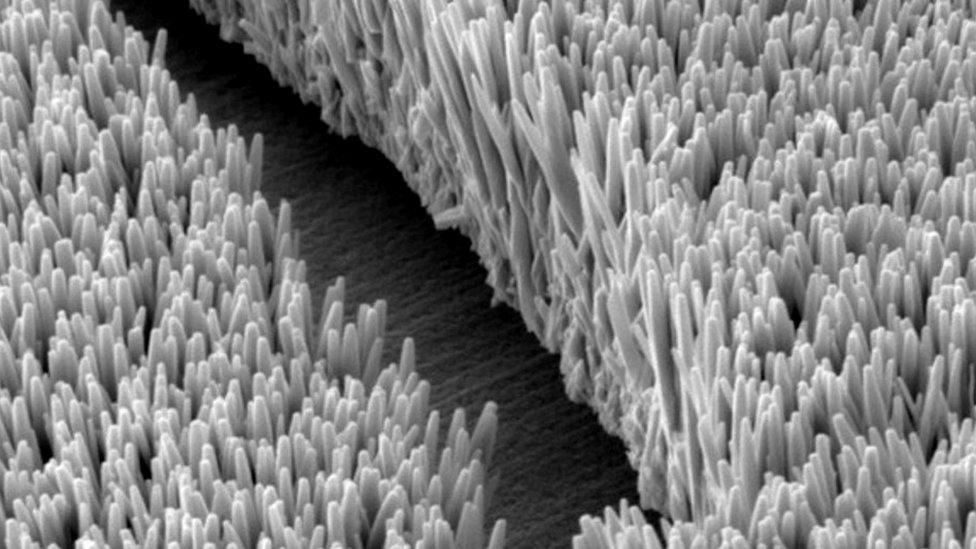

A thin layer mimics the structure of the intestines

Scientists have designed a new prototype battery that mimics the structure of the human intestines.

It's a type of battery called lithium-sulphur, which - in theory - could have five times the energy density of the lithium-ion forms in wide use today.

But the prototype developed by a UK-Chinese team overcomes a key hurdle to their commercial development by taking inspiration from the gut.

Details appear in the journal Advanced Functional Materials.

Scientists are tackling the challenge of improving battery technology using a variety of different approaches; this is one of them.

One of the problems hindering the commercial development of lithium-sulphur-based devices has been the degradation of the batteries caused by the loss of active materials within.

To overcome this problem, the researchers developed a lightweight layer with nano-scale structure which resembles the villi - finger-like protrusions which line the small intestine.

Battery basics

Electrode: Batteries contain two types of electrode where reactions take place. A reaction in one generates electrons and a reaction in the other absorbs them, yielding electrical energy

Electrolyte: Usually a liquid or gel containing an acid, base or salt. In batteries, it is the medium that allows electric charge to flow between the two electrodes

In humans, villi are used to absorb the products of digestion and increase the surface area across which this process can take place.

In the new lithium-sulphur battery, a layer of material with a villi-like structure, made from tiny zinc oxide wires, is placed on the surface of one of the battery's electrodes.

This can trap fragments of the active material when they break off, keeping them accessible for ongoing reactions and allowing the material to be reused.

Sulphur-based batteries could be a replacement for the lithium-ion batteries in wide use today

"It's a tiny thing, this layer, but it's important," said study co-author Dr Paul Coxon from the University of Cambridge's department of materials science and metallurgy.

"This gets us a long way through the bottleneck which is preventing the development of better batteries."

The researchers say that, if hurdles to commercial development can be overcome, lithium-sulphur batteries could have five times the energy density of the lithium-ion batteries used in smartphones and other electronics.

But as lithium-sulphur batteries discharge, sulphur molecules transform into chain-like structures known as poly-sulphides.

As the devices undergo several charge-discharge cycles, bits of the poly-sulphide go into the battery's electrolyte (the electrically-conducting solution), so that over time the battery loses active material.

"This is the first time a chemically functional layer with a well-organised nano-architecture has been proposed to trap and reuse the dissolved active materials during battery charging and discharging," said lead author Teng Zhao, a PhD student from Cambridge.

"By taking our inspiration from the natural world, we were able to come up with a solution that we hope will accelerate the development of next-generation batteries."

The device is currently a proof of principle; commercially-available lithium-sulphur batteries are still some years away.

Additionally, while the number of times the battery can be charged and discharged has been improved, it is still not able to go through as many charge cycles as a lithium-ion battery.

But the researchers point out that, given a lithium-sulphur battery does not need to be charged as often as a lithium-ion battery, it may be the case that the increase in energy density cancels out the lower total number of charge-discharge cycles.