What does Trump win mean for US science?

- Published

Mr Trump has been most vocal on the issues of climate change and energy

President-elect Donald Trump did not express many views about science and innovation on the campaign trail. But there are some clues to his positions on key issues.

Since Tuesday, many scientists have been laying out their concerns about the future of the US research community under a Trump administration.

Before the election, the non-profit organisation Science Debate asked the main candidates, external to outline their positions on different scientific points.

Mr Trump's vision for innovation in the country that currently spends most in the world, external on research and development reflects his businessman's perspective.

"Innovation has always been one of the great by-products of free market systems. Entrepreneurs have always found entries into markets by giving consumers more options for the products they desire," he explained.

But some in the scientific community are fearful about funding for basic research - fundamental science aimed at bettering our understanding of the world around us.

This is distinct from applied research, which is concerned with practical applications of science driven, for example, by commercial considerations.

And there are concerns that Mr Trump's professed stance on immigration will stymie American universities' ability to attract the best scientific talent from around the world.

Robin Bell, the incoming president of the American Geophysical Union, told the Washington Post, external newspaper: "There's a fear that the scientific infrastructure in the US is going to be on its knees," adding: "Everything from funding to being able to attract the global leaders we need to do basic science research."

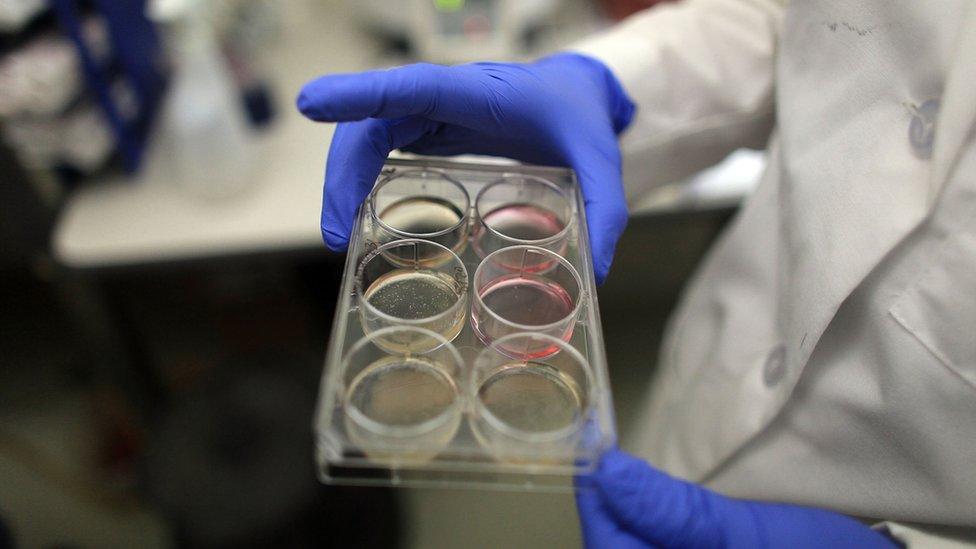

Scientists are concerned that medical research could be hit under cuts to federal spending

In his responses to Science Debate, Mr Trump does say that the federal government should "encourage innovation in the areas of space exploration and investment in research and development across the broad landscape of academia".

He acknowledges that scientific advances "do require long-term investment", but he also raises the possibility of cuts, saying: "There are increasing demands to curtail spending and to balance the federal budget".

And he adds: "We should also bring together stakeholders and examine what the priorities ought to be for the nation."

It is the uncertain detail of this potential shift in priorities that some scientists fear.

Some researchers feel that Mr Trump's statements about climate change betray a disregard for the scientific method that does not augur well for other research areas under his administration.

The president-elect has called global warming a "hoax" and vowed to "cancel" the Paris agreement, which came into force earlier this month.

Last year, Mr Trump did briefly comment on the National Institutes of Health (NIH), external, which oversees some $30bn of medical research each year.

Right-wing talk show host Michael Savage asked the then-presidential candidate whether he would consider appointing him to head the NIH.

Mr Trump answered: "I think that's great," adding: "You know you'd get common sense if that were the case, that I can tell you, because I hear so much about the NIH, and it's terrible."

Whether this brief, presumably off-the-cuff exchange gives any serious insight into Mr Trump's position on biomedical research is unclear.

Responding to a Science Debate question about federal research for public health, Mr Trump replied: "In a time of limited resources, one must ensure that the nation is getting the greatest bang for the buck. We cannot simply throw money at these institutions and assume that the nation will be well served."

He added: "What we ought to focus on is assessing where we need to be as a nation and then applying resources to those areas where we need the most work."

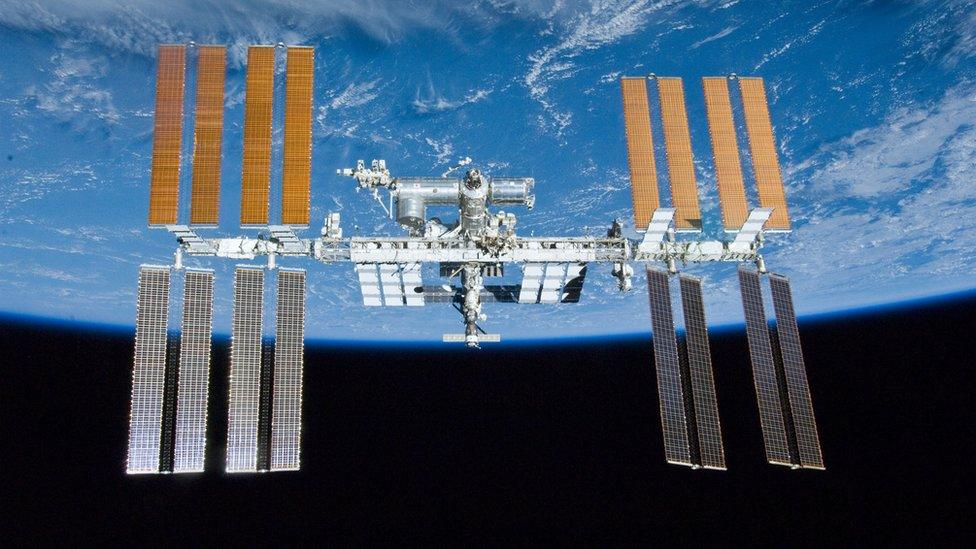

Mr Trump has expressed his enthusiasm for space exploration

However, there seemed to be few caveats to Mr Trump's enthusiasm for space exploration.

"Space exploration has given so much to America, including tremendous pride in our scientific and engineering prowess. A strong space program will encourage our children to seek STEM educational outcomes," he said.

But what exactly that will mean for the balance of distinct Nasa programmes, such as human spaceflight, robotic exploration and Earth observation, remains unsettled.

Earth observation - with its links to climate change science - suffered cuts under President George W Bush, and experts in that field will be waiting to see whether that is repeated under this administration.

In the last weeks of the campaign, Mr Trump appointed Robert Walker, a former congressman, to draw up a space policy. In Space News, Mr Walker outlined nine aspects of the plan, external.

And the President-elect's Republican ally Newt Gingrich - who has been tipped for a top job in the new administration - has been outspoken, external about what the US space agency should and shouldn't be doing.

Many uncertainties remain about Mr Trump's attitude towards science. Yet some researchers are positive about their prospects over the next four years.

Stanley Young, assistant director for bioinformatics at the National Institute of Statistical Sciences, told Nature News, external: "The popular impression I get is Clinton would go forward with business as usual and Trump is likely to upset things a bit. There's a lot that could be improved in science."

Follow Paul on Twitter. , external