Pluto 'has slushy ocean' below surface

- Published

A subsurface ocean could explain some of Pluto's puzzling alignment with its moon Charon

Pluto may harbour a slushy water ocean beneath its most prominent surface feature, known as the "heart".

This could explain why part of the heart-shaped region - called Sputnik Planitia - is locked in alignment with Pluto's largest moon Charon.

A viscous ocean beneath the icy crust could have acted as a heavy, irregular mass that rolled Pluto over, so that Sputnik Planitia was facing the moon.

The findings are based on data from Nasa's New Horizons spacecraft.

The space probe flew by the dwarf planet in July 2015 and is now headed into the Kuiper Belt, an icy region of the Solar System beyond Neptune's orbit.

Sputnik Planitia is a circular region in the heart's left "ventricle" and is aligned almost exactly opposite Charon. In addition, Pluto and Charon are tidally locked, which results in the objects always showing the same face to each other.

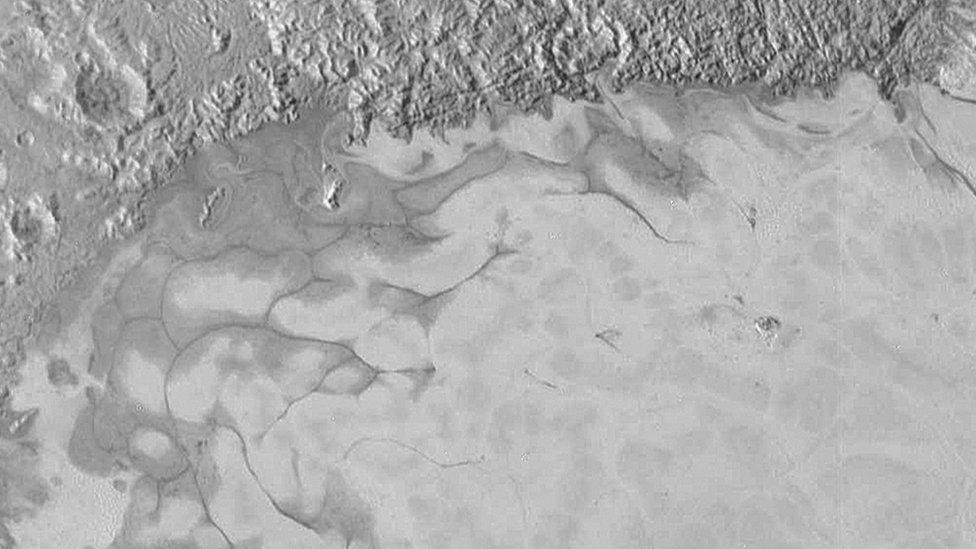

New Horizons saw evidence of flowing nitrogen ice, analagous to glaciers on Earth

"If you were to draw a line from the centre of Pluto's moon Charon through Pluto, it would come out on the other side, almost right through Sputnik Planitia. That line is what we call the tidal axis," said James Keane, from the University of Arizona, co-author of one of a pair of papers published on the subject in Nature journal.

This is strongly suggestive of a particular evolutionary course for Pluto. The researchers contend that Sputnik Planitia formed somewhere else on Pluto and then dragged the entire dwarf planet over - by as much as 60 degrees - relative to its spin axis.

Slushy pup?

He explained: "If you have a perfectly spherical planet... and you stick a lump of extra mass on the side and let it spin, the planet will re-orient to move that extra mass closer to the equator. For bodies like Pluto that are tidally locked, it will move it toward that tidal axis - the one connecting Pluto and Charon."

Prof Francis Nimmo, from University of California, Santa Cruz, one of the authors of a separate study in Nature, told the BBC's Inside Science radio programme: "There's more mass in Sputnik Planitia than in surrounding regions - so somehow there's extra stuff there."

Charon is Pluto's largest moon; the two bodies always show the same face to one other

But there's a problem with this idea, because the feature is thought to be the result of an impact with another object at some point in Pluto's past.

"Sputnik Planitia is a hole in the ground, so there shouldn't be more weight, there should be less weight. If the story is correct, you have to find some way of hiding extra mass underneath the surface of Sputnik Planitia," said Prof Nimmo.

"If you take some of the ice beneath Sputnik Planitia and replace it with water, water is denser than ice... so you'd be adding extra mass. That would help Sputnik Planitia to have more mass overall."

If a massive impact created the basin, it may have also triggered any material - such as a slushy ocean - beneath the surface to push Pluto's thin crust outward, causing a "positive gravitational anomaly" that would have caused the dwarf planet to roll over.

Prof Martin Siegert, from Imperial College London, who was not involved with either study, called the result "fascinating".

"The ocean would be incredibly cold, and hyper saline (I think they said enriched in ammonia), so unlike water on Earth or Europa," he told the BBC News Website.

"It would certainly be an extreme environment! Perhaps the most extreme in the Solar System?"

New Horizons was launched on its way to Pluto in 2006

But James Keane thinks phenomena other than a subsurface ocean could explain the alignment of Sputnik Planitia with Charon.

"Sputnik Planitia is filled with several kilometres of volatile ices. These ices are predominantly things that we think of as gases here on Earth - nitrogen, methane and carbon monoxide. On Pluto these are solid, and they behave almost like glaciers do on Earth," he said.

His team's explanation focuses on the nitrogen ice: "Each time Pluto goes around the Sun, a bit of nitrogen accumulates in the heart... once enough ice has piled up, maybe a hundred metres thick, it starts to overwhelm the planet's shape, which dictates the planet's orientation.

"If you have an excess of mass in one spot on the planet, it wants to go to the equator. Eventually, over millions of years, it will drag the whole planet over."

But he added: "It's hard to distinguish between either scenario, so both teams will have to do future work to try to test both hypotheses."

New Horizons, which is about the size of a baby grand piano, was launched on 14 January 2006 from Cape Canaveral in Florida. After its flyby of Pluto, mission scientists identified a second target - an icy Kuiper Belt body called 2014 MU69 - which the probe should reach in 2019.

Follow Paul on Twitter., external