'Smart boulders' record huge underwater avalanche

- Published

A submersible feeds images back to the surface of a "smart boulder" on the seafloor

Scientists have had a remarkable close-up encounter with a gigantic underwater avalanche.

It is the first time researchers have had instruments in place to monitor so large a flow of sediment as it careered down-slope.

The event occurred in Monterey Canyon off the coast of California in January.

The mass of sand and rock kept moving for more than 50km, as it slipped from a point less than 300m below the sea surface to a depth of over 1,800m.

Speeds during the descent reached over 8m per second.

An international team running the Coordinated Canyon Experiment (CCE), external is now sitting on a wealth of data.

"These flows, called turbidity currents, are some of the most powerful flows on Earth," said Dan Parsons, a professor of process sedimentology, at the University of Hull, UK.

"Rivers are the only other mechanism that transports comparable volumes of sediment across the globe. However, although we have hundreds of thousands of measurements from rivers, we only have a small handful of measurements from turbidity currents – often for short periods of time and at only one position within a system."

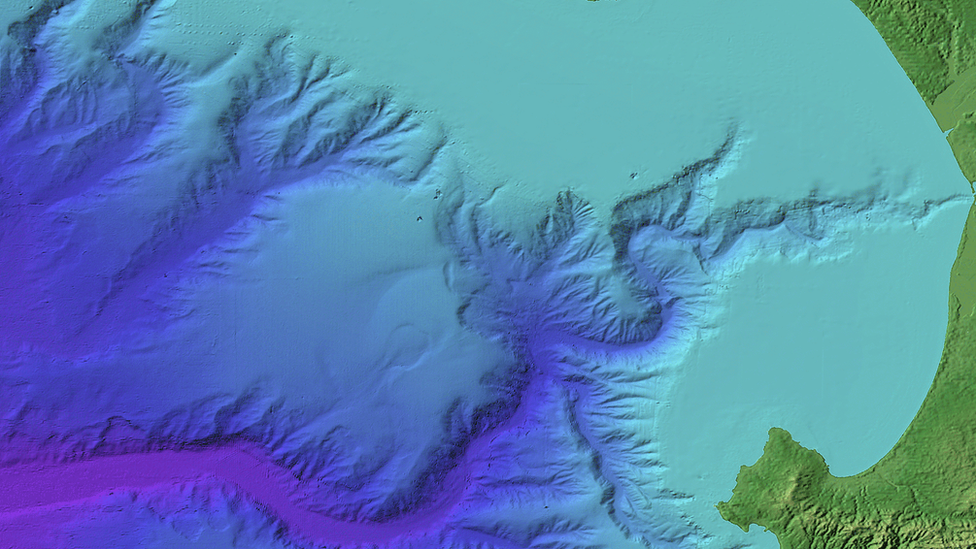

A visualisation of Monterey Canyon falling away from the California coast

Sited on the California coastline where the canyon falls away into the Pacific is the Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute, external.

MBARI has been the launch pad for scientists these past few years to go out and place an array of sensors in the underwater gorge.

The instrumentation records flow velocity and how much sediment the flows contain

Some of these instruments, which are lowered to the seafloor from boats, look like Mars landers.

One recent innovation is the Benthic Event Detector (BED). "Think 'smart boulder'," said MBARI’s Prof Charlie Paull, who gave details of the 15 January event here at the Fall Meeting of the American Geophysical Union, external.

"The BED is a 44cm sphere. It has an electronic package entombed within in it; it measures pressure and orientation, and will record how it moves down the canyon floor. And we use the BEDs to see the progression of the turbidity current as it rolls over one BED after another," he told BBC News.

The force of these colossal flows of sediment has been known to sever the underwater cables that carry telecommunications around the globe.

It was no surprise therefore to hear that the CCE’s instruments had an extremely rough ride on 15 January.

Some sensors with anchors weighing more than a tonne were dragged 7km down the canyon. But what they recorded will be invaluable to the scientists as they seek to learn more about how turbidity currents are triggered, and how they actually work; how the material - what amounts to a kind of slurry - moves along the seafloor.

Researchers are rapidly recognising the huge role they play in all manner of Earth processes.

On the grand scale, they are the end stage in a cycle that starts with tectonics and the pushing up of mountains, and which is then followed by erosion and the transport of sediments down rivers to the coasts.

It is turbidity currents that ultimately return a lot of this material to the deep ocean.

Some of the instrument platforms look like Mars landers

More than 400,000 cubic metres of sediment is thought to be travelling down Monterey Canyon each year on this final leg of the cycle.

"The flows are responsible for flushing sediments, nutrients and organic carbon into the deep ocean, which can sustain life on the abyssal plain," explained Prof Parsons.

"These novel measurements in the Monterey Canyon, utilising state-of-the art robotics and sensors, are allowing us to make a step change in our understanding of turbidity currents."

And Prof Paull added: “The existence of these flows was something that was first described and inferred from rock deposits on land that had been pushed up. A lot of great work.

"They have been heavily modelled mathematically since, there have been a lot of flume studies, and remote-sensing surveys have looked at the deposits associated with them. But you notice what I left out from that list was actually making direct, physical measurements.

"There've been precious few made before this event and a good portion of those measurements were made in Monterey Canyon in anticipation for the CCE project."

MBARI's Prof Paull leads the CCE project in collaboration with researchers from the United States Geological Survey, the Ocean University of China, the UK’s National Oceanography Centre in Southampton, the University of Durham, and the University of Hull.

Jonathan.Amos-INTERNET@bbc.co.uk, external and follow me on Twitter: @BBCAmos, external