Sentinels map Earth's slow surface warping

- Published

Artwork: The Sentinel radar satellites produce prodigious volumes of data

British researchers are now routinely mapping a great swathe of Earth's surface, looking for the subtle warping that ultimately leads to quakes.

The team is processing satellite images to show how rocks in a belt that stretches from Europe's Alps to China are slowly accumulating strain.

Movements on the scale of just millimetres per year are being sought.

The new maps are being made available to help researchers produce more robust assessments of seismic hazard.

The kind of change they are trying to chart is not noticeable in the everyday human sense, but over time will put faults under such pressure that they eventually rupture - often with catastrophic consequences.

"We may well discover regions that have very small strain rates that we have not been able to detect before," said Dr Richard Walters.

"And that may well tell us that earthquakes are more likely in some areas that traditionally have been thought of as being completely stable and not at risk of having earthquakes at all."

Richard Walters: "We're trying to track a slow elastic warping"

Dr Walters is affiliated to the UK Centre for Observation and Modelling of Earthquakes, Volcanoes and Tectonics (COMET, external).

He announced the start of the new service, external here in San Francisco, at the Fall Meeting of the American Geophysical Union.

Key to the UK scientists' work is the high performance of the EU's new Sentinel-1 radar satellites.

This pair of spacecraft repeatedly and rapidly image the surface of the globe, throwing their data to the ground using a high-speed laser link. And by comparing whole stacks of their pictures in a technique known as interferometry, the COMET group can begin to see the very slow bending and buckling that occurs in the crust as a result of shifting tectonic plates.

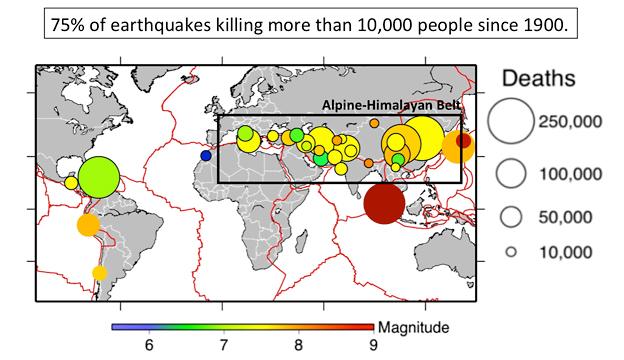

To initiate the service, the researchers are concentrating on the Alpine-Himalayan seismic belt.

This is the sector where most of the deaths arising from big earthquakes occur.

In time, however, the mapping exercise will be extended to cover all major seismic hazard zones, including the rim of the Pacific basin - the so-called "ring of fire", where large tremors are also a regular occurrence.

The exercise is concentrating for starters on a key belt for seismic hazard

To be really effective, the team's maps need to be sensitive to movements of about 1mm per year over 100km.

The system is not quite there yet, but as the Sentinels gather more and more images, the desired standard should be realised.

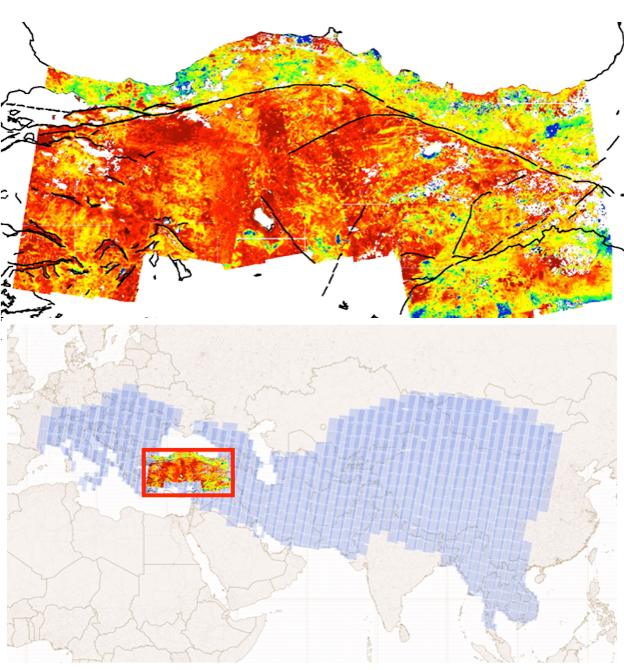

As a proof of principle - and to give an example of what the new system can do - the COMET group showed off its maps of Turkey at AGU.

These capture the 20-25mm/year westwards march of the Anatolian plateau relative to Eurasia.

The focus of interest is how tectonic strain is building up along the North and East Anatolian Faults - the trigger points for so many damaging quakes in the past.

The westwards march (red colour) of the Anatolian plateau relative to Eurasia. Turkey, which lies within the Alpine-Himalayan belt, has suffered many damaging quakes

Prof Tim Wright, the director of COMET, said one of the breakthroughs that had made the new service possible was simply the prodigious volumes of data the Sentinel satellite system could now feed to the ground.

"To give you an example, in just one year of Sentinel operation there are 156 terabytes of data; whereas the entire 10-year archive of Envisat (a previous European radar satellite) has just 24TB.

"And we now process the data from the Sentinels automatically within a few hours of getting it."

Dr Walters added: "This is a big data project. We've had funding from the UK's Natural Environment Research Council to build a big data-processing facility, to take these data from the European Space Agency, which they provide for free, and make useful geophysical measurements.

"We then serve that to the community. We put the data out there not just for us to analyse and think about seismic hazards, but for scientists all over the world to use."

The "Looking inside the Continents from Space" project, external has just sent live a website where all the processed maps can be accessed.

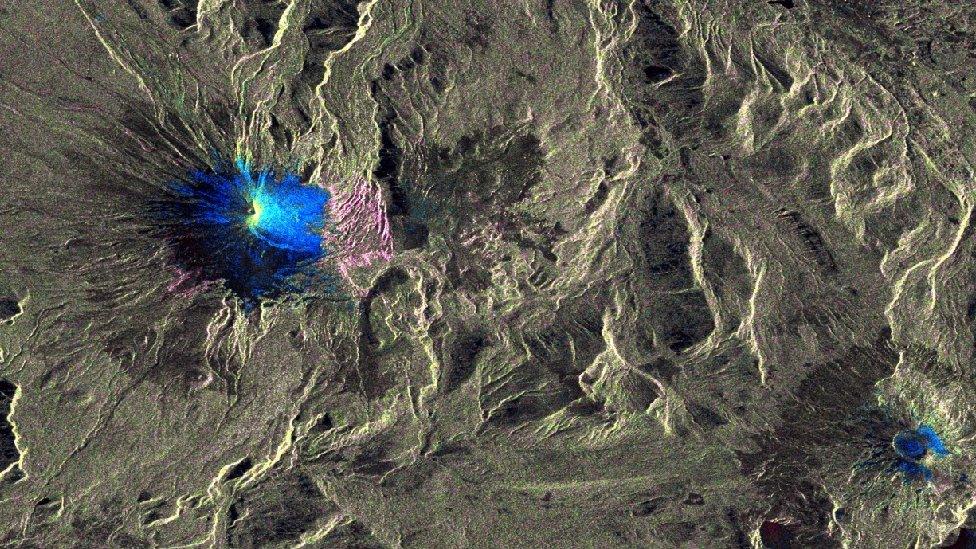

COMET is also working on a very similar system that would allow scientists to track the behaviour of volcanoes. The Sentinels will also see their slow developing bulges of magma that may precede eruptions.

Sentinel radar data reveals changes (blue) in the shape of Villarrica volcano in Chile

Jonathan.Amos-INTERNET@bbc.co.uk, external and follow me on Twitter: @BBCAmos, external