Antarctic 'pole of ignorance' finally addressed

- Published

It took several years to organise the permissions to fly into the South Pole

The last major unknown region on Earth has just been surveyed: the South Pole.

Although the Americans have had a base at the bottom of the planet for decades, what lies underneath the thick ice there has been a mystery.

Now, European scientists have flown instruments back and forth across the pole to map its hidden depths.

As well as finding previously unknown valleys and mountains, the team says it has acquired important data that will have uses far from Antarctica.

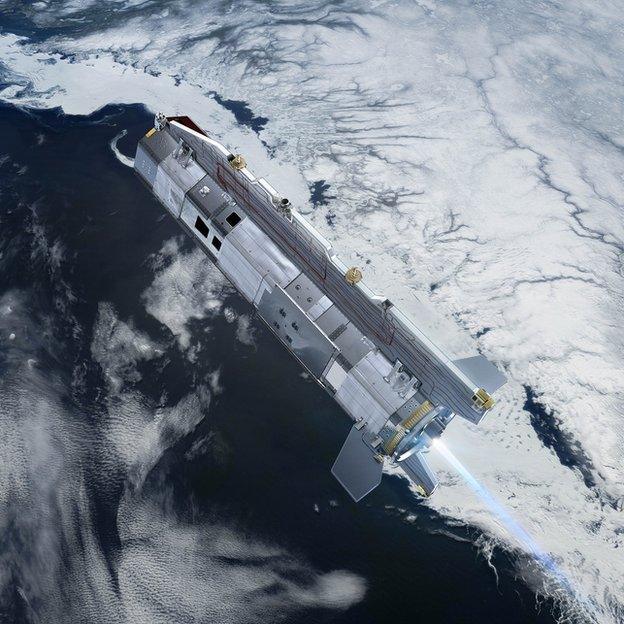

Known as PolarGAP, external, the project was largely funded by the European Space Agency (Esa) to gather measurements over an area of Earth that its satellites cannot see, as they generally only fly up to about 83 degrees in latitude.

Fausto Ferraccioli: "The South Pole has been one of the largest 'poles of ignorance'"

In particular, Esa wanted to understand the pole's gravity field, to complete the dataset gathered by its recent gravity-sensing spacecraft, GOCE.

But in plugging this data hole, the project has also now helped scientists to realise their century-long quest to describe how the pull of gravity varies across the entire Earth.

Prof René Forsberg from the National Space Institute at the Technical University of Denmark (DTU-Space) said gravity data was fundamental knowledge needed to understand height across the planet. GPS and other satellite systems depended on having a universal reference, he explained.

"The PolarGAP data will make future global models much more accurate, and together with similar data collected over decades in the Arctic, including data from recent [UN treaty] activities and declassified gravity data from the Cold War, secure 100% global coverage," he told BBC News.

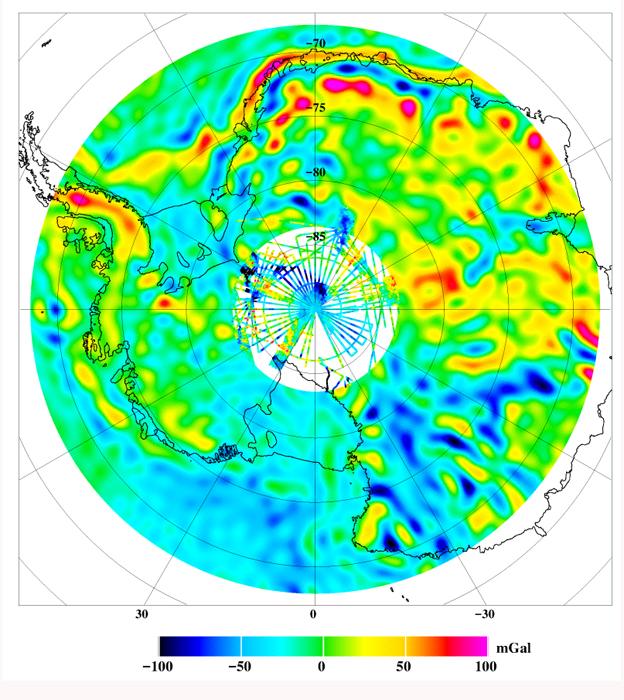

A gravity map of Antarctica from GOCE with the new PolarGAP data filling the satellite's hole. The highs and lows correspond mainly to subglacial terrain

To get its information, the PolarGAP team flew an instrumented Twin Otter plane across the polar landscape in grid lines that totalled some 30,000km.

As well as gravity and magnetic sensors, the airborne campaign carried a radar and a laser altimeter.

The radar provides insights on the layers and total thickness of the ice sheet. It also maps the shape of the rockbed and gives some information on the movement of water at the ice-rock interface.

Gravity data helps determine the thickness of the crust - the platform on which Antarctica stands. Magnetics is complementary and says something about the presence of magmatic rocks and sedimentary basins.

The laser captures the shape of the top ice surface.

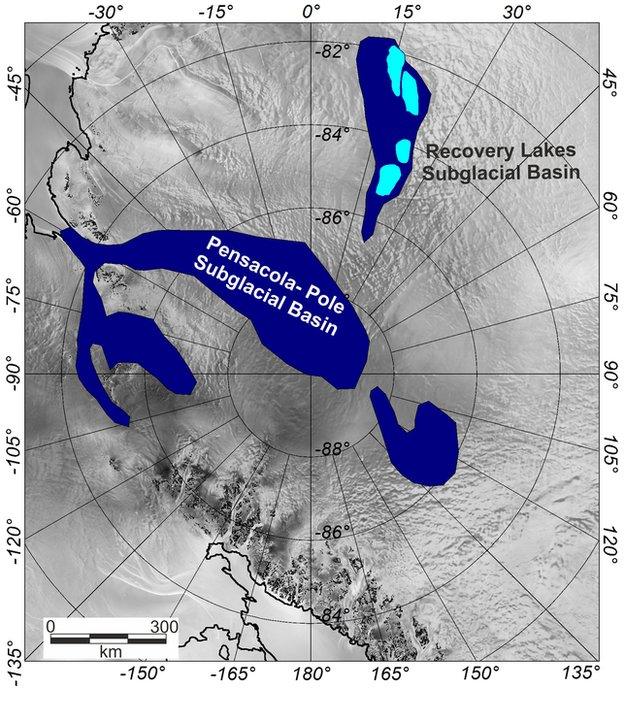

Much of this data is still being processed, but already the team can confirm the existence of a vast basin that appears to play a key role in controlling the flow of ice towards the ocean.

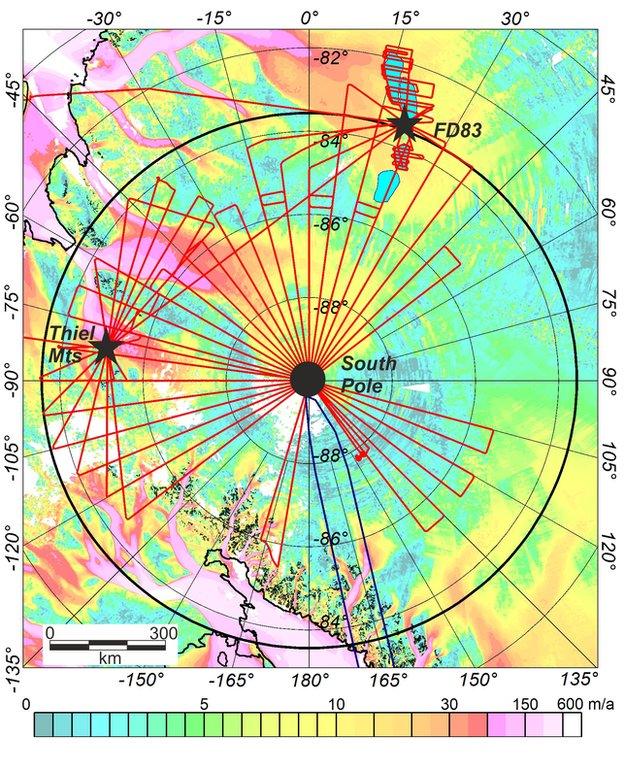

In this image, the Twin Otter flight lines (red) are laid over a map of ice velocity. The giant circle is the "hole" that satellites cannot see. The plane operated out of Thiel Mountains and FD83 Camp, with re-fuelling at South Pole

"It's an over 1,000km-long basin that extends from the Weddell Sea right down to the pole," said British Antarctic Survey (BAS) team-member Dr Fausto Ferraccioli.

"It's really one of the major features of the Antarctic continent and it's likely to have very large significance because it underlies some of the fastest flowing ice streams in this region."

Pensacola Pole Subglacial Basin was suspected from previous, limited survey work. Its existence, scale and structure are now confirmed by the PolarGAP project

The survey's information - which was presented this week at the American Geophysical Union meetin, externalg in San Francisco - will have multiple applications.

One will be to help guide a hunt for the oldest ice on the White Continent - ice that's perhaps a million and a half years old. Its chemistry would provide important new insights on how Earth's climate has changed.

Another use will be to assist geologists in their choice of location to drill to the rockbed. No-one has yet pulled up rock samples from under the middle of the Antarctic ice sheet.

Flat white from horizon to horizon - except in the Transantarctic Mountains

PolarGAP was conducted by a multi-nation group that included the Norwegian Polar Institute, as well as DTU-Space Denmark and the British Antarctic Survey. The project also needed the support of the US National Science Foundation, which re-fuelled the Twin Otter on the sorties that went into South Pole station.

Dr Tom Jordan, also from BAS, said the survey conducted in the last Antarctic summer season had been an extraordinary experience.

"Although the view was flat white from horizon to horizon, there were moments of real awe-inspiring and almost alien beauty, in particular as we flew out over the Transantarctic Mountains," he told BBC News.

"The other thing I really enjoyed about running the campaign was working with the close knit and dedicated international team.

"Each member brought different but vital skills to the project, and the sense that together we were able to achieve a really fantastic piece of work was really great."

Esa's GOCE mission gathered high resolution data on gravity variations across the globe, but its orbit meant it could not see the poles

Jonathan.Amos-INTERNET@bbc.co.uk, external and follow me on Twitter: @BBCAmos, external