Iron 'jet stream' detected in Earth's outer core

- Published

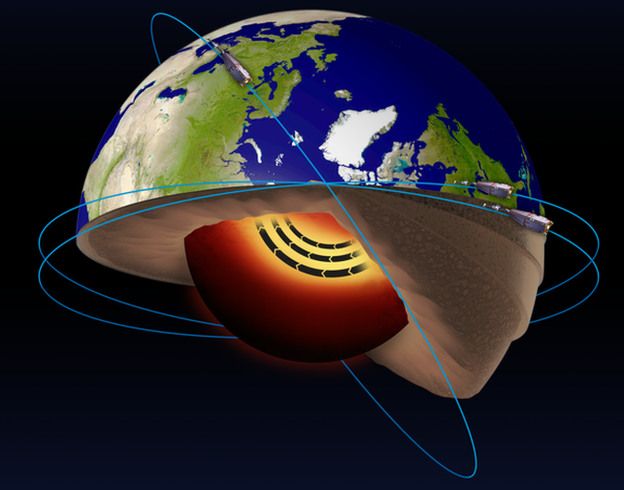

Artwork: A depiction of where the jet is moving - in the outer core. The Swarm satellites fly a few hundred km above the planet and sense its magnetic field

Scientists say they have identified a remarkable new feature in Earth’s molten outer core.

They describe it as a kind of "jet stream" - a fast-flowing river of liquid iron that is surging westwards under Alaska and Siberia.

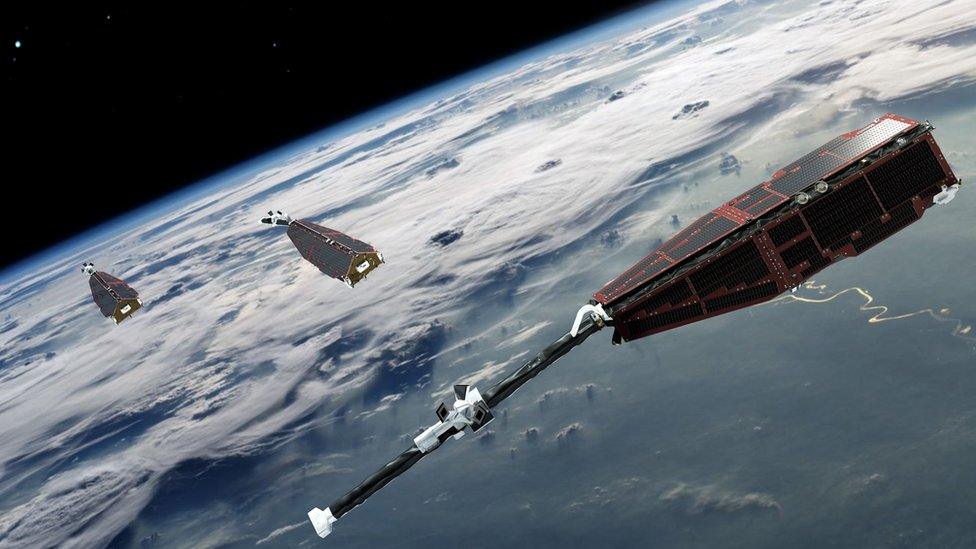

The moving mass of metal has been inferred from measurements made by Europe’s Swarm satellites, external.

This trio of spacecraft are currently mapping Earth's magnetic field to try to understand its fundamental workings.

The scientists say the jet is the best explanation for the patches of concentrated field strength that the satellites observe in the northern hemisphere.

"This jet of liquid iron is moving at about fifty kilometres per year," explained Dr Chris Finlay from the National Space Institute at the Technical University of Denmark (DTU Space).

“That might not sound like a lot to you on Earth's surface, but you have to remember this a very dense liquid metal and it takes a huge amount of energy to move this thing around and that's probably the fastest motion we have anywhere within the solid Earth,” he told BBC News.

Dr Finlay was speaking here at the American Geophysical Union (AGU) meeting, external in San Francisco, just ahead of the official publication of the research in the journal Nature Geoscience, external.

Artwork: The Swarm satellites were launched in 2013 to study Earth's magnetic field

Most people will be familiar with the atmospheric jet stream - the high-altitude, rapidly flowing belt of air on which aeroplanes ride to get to their destination more quickly.

Dr Finlay and colleagues want us to envision something similar but made of metal and 3,000km down, under our feet.

They assess the jet to be about 420km wide, and say it wraps half-way around the planet.

Its behaviour will be critical to the generation and maintenance of the global magnetic field, they add.

“It's likely that the jet stream has been in play for hundreds of millions of years," said Dr Phil Livermore from Leeds University, UK, and the lead author on the journal paper.

In the paper, the team puts forward a model to explain the jet.

The major part of Earth’s magnetic field is generated via convection of molten iron in the outer core. The field protects all life from damaging space radiation

The scientists say the feature probably aligns to a boundary between two different regions in the core.

They call this boundary the "tangent cylinder". They imagine this as a tube sitting around the solid inner core, running along Earth’s rotation axis.

When liquid iron approaches the boundary from both sides, it gets squeezed out sideways to form the jet, which then hugs the imaginary tube.

"Of course, you need a force to move fluid towards the tangent cylinder," said Prof Rainer Hollerbach, also from Leeds and another co-author on the paper.

"This could be provided by buoyancy, or perhaps more likely from changes in the magnetic field within the core."

Although the team believes it understands how wide and how long the jet is, the depth to which it descends is far from certain.

Dr Livermore told BBC News: "It currently wraps about 180 degrees around the tangent cylinder. Although observations only constrain the jet stream on the edge of the core, our theoretical understanding suggests that the jet could in principle go very deep indeed - possibly in fact all the way down to the edge of the core in the southern hemisphere (i.e. at the other end of the tangent cylinder)."

That the team can make such inferences speaks to the impressive capabilities of the Swarm constellation.

Launched in November 2013, the European Space Agency satellites are providing unparalleled insights into the structure and behaviour of Earth's magnetic field.

With their highly sensitive instruments, they are gradually teasing apart the field's various components - from the dominant signal coming from the movement of iron in the outer core to the almost imperceptible contribution made by ocean currents.

It is hoped the Swarm satellites’ data could ultimately tell us why Earth’s magnetic field has been weakening in recent centuries.

Scientists have speculated we could be on the cusp of a polarity reversal, which would see North become South, and South become North.

This occurs every few hundred thousand years.

Jonathan.Amos-INTERNET@bbc.co.uk, external and follow me on Twitter: @BBCAmos, external