Big digs: The year 2016 in archaeology

- Published

2016 had its fair share of exciting discoveries in the world of archaeology. Together, they reveal the human characteristics that unite us all and expose the impacts that past peoples continue to have on life today. Here's a selection of the most inspiring findings of the year.

Britain's Pompeii

A reconstruction of the elite settlement by illustrator Vicki Herring

Some of the most dramatic British archaeology this year was recovered from the unassuming landscape of Must Farm Quarry near Peterborough. Nine Bronze Age logboats had been discovered in a prehistoric river channel in 2011, alongside fishtraps and weapons. This year, the excavation of an adjacent settlement preserved in the river silts threw open another window on to life in Bronze Age Britain.

Three thousand years ago, a cluster of roundhouses built on stilts over the river were destroyed by fire. A discarded bowl - containing the remains of a meal and a wooden spurtle (stirring stick) - shows the haste with which the settlement was abandoned.

An exceptional example of an intact two-piece axe haft complete with socketed bronze axe

Like Pompeii, the sudden misfortune of the occupants gave archaeologists a staggering opportunity to see Bronze Age life frozen in time. The earliest complete cartwheel in the UK, hafted bronze tools, balls of thread, sets of storage jars, cups and bowls, wooden boxes and buckets, foot and hoof prints, and delicate fragments of cloth are just some of the enigmatic artefacts that were found across the site.

It's possible that the settlement's position on the river allowed this group to control trade along the waterways. The inhabitants certainly appear to be relatively wealthy. Imported beads of glass and amber suggest that these people were prosperous and well-connected to the continent. But a burning question remains: was the fire an accident, or did this privileged group fall victim to an arson attack?

Crossing continents

A mastodon leg bone is retrieved from the Page-Ladson site in the Aucilla River, Florida

At another waterlogged site in the middle of a Florida river, archaeologists had a further rare encounter with the past. Underwater archaeologists at the site of Page-Ladson found stone tools that are around 14,550 years old.

This remarkable discovery adds to growing evidence that is challenging ideas of how humans populated North America. Traditionally, hunter-gatherers are thought to have crossed the Bering land bridge into the Americas from northeast Asia no earlier than 13,000 years ago, quickly hunting local populations of megafauna to extinction.

The Page-Ladson site pushes back that date by more than a thousand years. Interestingly, the stone tools in question were found alongside the remains of now-extinct megafauna.

Cut marks on a tusk from the site showed that people had hunted or scavenged a mastodon, proving that human populations co-existed with such megafauna for at least two thousand years before they became extinct.

Feline friends

In a different story of animal interactions, ancient DNA has now been used to explore when and where cats were domesticated. A team analysed the remains of over 200 cats from archaeological sites in Eurasia and Africa from the past 10,000 years.

They found that wild cats probably developed a mutually-beneficial relationship with early farmers in the Near East at the start of agriculture. These cat populations grew and spread with farming communities to the eastern Mediterranean, southeast Europe and beyond.

Animals were mummified in ancient Egypt for thousands of years

Stores of grain kept by these groups would have attracted rodents, which in turn attracted cats, sparking the process of domestication. A cat skeleton found in a human burial in Cyprus suggests that cats played a role in household life from as early as 9,500 years ago.

A separate expansion of Egyptian cat populations occurred several thousand years later, spreading through Africa and Eurasia, travelling with people over land but also by sea.

Ancient seafaring cats - taken on board ships to stop rodents destroying precious cargos and provisions - probably helped the rapid spread of cats to all corners of the world, putting cats firmly on the map.

Warming our world

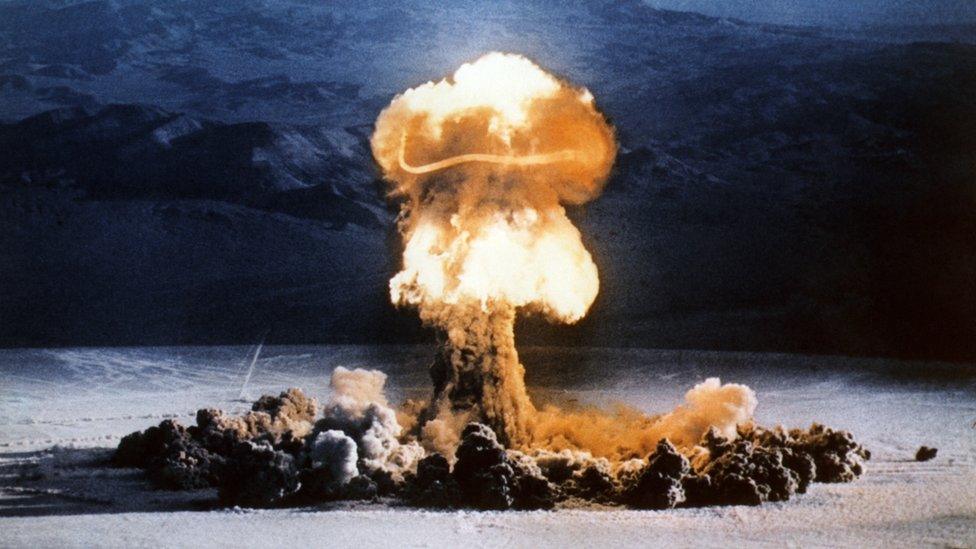

Not without controversy, it has now been recommended that the Anthropocene should be formalised as a geological epoch, beginning at AD 1950: the "nuclear age".

The advent of the nuclear age is a proposed starting point for the new geological epoch

However, our impact on the environment is proving to be significantly older.

This year, while scientists presented further evidence that global warming was linked to industrial activity over the past 200 years, archaeologists argued that human impact on climate goes much further back.

In particular, early agriculture, livestock farming and deforestation may have released high levels of greenhouse gases into the atmosphere from as early as 10,000 years ago.

Researchers looked at methane and carbon dioxide levels in Antarctic ice cores to establish the norms of the glacial cool periods and warmer interglacial periods of the past 800,000 years. This allowed them to ask whether the course of our current interglacial is a natural phenomenon, or the result of human changes to the environment.

They found that early farming produced changes in the atmosphere long before the industrial revolution, slowing down the Earth's natural cooling and possibly preventing us from entering the next ice age.

An archaeology of care

On a more personal level, archaeologists in the American southwest found a burial that told a touching story of a young disabled woman and those that took care of her.

The burial was found at a large Hohokam settlement site dating to AD 700-1400, now hidden under the streets of the city of Tempe, Arizona.

Through much, if not all of her lifetime, this woman suffered from scoliosis so severe that walking would have been difficult or impossible.

Added to this, her bones bore the tell-tale signs of both tuberculosis and, unexpectedly, rickets - an unusual condition in the sunny deserts of the southwest, but one that suggests she had limited mobility and was unable to go outside.

Despite these conditions, she survived into her twenties, intensively cared for by others in her community who brought her food and attended to her day-to-day needs. After she died, she was buried with grave goods far in excess of others.

This one individual tells us a lot about the values of Hohokam culture. This young woman was clearly a respected member of the community, and was treated with special status not only during her life, but also after her death.

Other exciting archaeological stories from 2016:

• The discovery of an engraved pendant at the site of Star Carr caused a sensation this year. The item - which is around 11,000 years old - is the earliest example of Mesolithic art found in Britain.

This 11,000-year-old pendant from Star Carr is the earliest example of Mesolithic art in Britain

• This year has also produced an archaeological clue as to the route taken by Hannibal and his army across the Alps, in the form of traces of horse manure dating to 200 BC. Elephant dung is yet to be found.

• The "space archaeologist", Sarah Parcak, won the 2016 TED Prize for her proposal to use crowdsourcing to discover new sites and monitor the looting of existing sites via satellite imagery.

• The unexpected prominence of women at Stonehenge was revealed earlier this year. At least 14 women - presumably of high status - were identified from cremated remains buried at the site between four and five thousand years ago.

• 87 waxed writing tablets from Roman London have had their inscriptions deciphered, revealing the concerns and business dealings of the inhabitants of the newly-established city nearly two thousand years ago.

Dr Louise Iles is a Leverhulme Early Career Fellow at the University of Sheffield