To see finally the face of Peggy

- Published

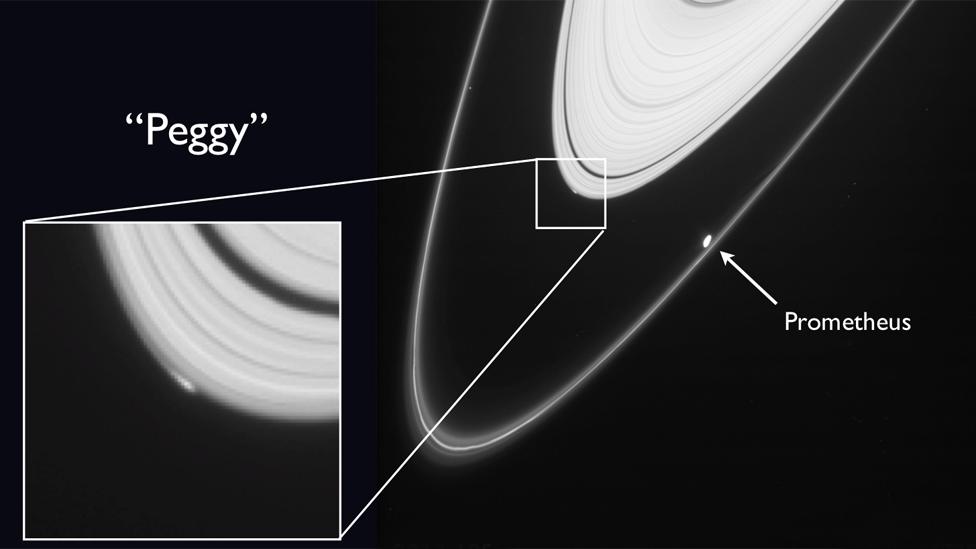

When first identified Peggy was picked up as a long, bright smudge at the edge of Saturn's A-ring

Will Peggy finally reveal herself?

Scientists studying the splendour of Saturn's rings are hoping soon to get a resolved picture of an embedded object they know exists but cannot quite see.

The moonlet is named after London researcher Carl Murray's mother-in-law, and was first noticed in 2013. Its effect on surrounding ice and dust particles has been tracked ever since.

But no direct image of Peggy's form has yet been obtained, and time is now short.

The Cassini spacecraft's mission at Saturn, external is edging to a close and its dramatic end-of-life disposal.

In September, the probe will be driven to destruction in the atmosphere of the giant planet, at which point the constant stream of pictures and other data it has returned these past 13 years will come to an abrupt end.

Carl Murray: "It's like an old friend to us, and so as you say goodbye you'd like to get a picture"

Carl Murray and his team at Queen Mary University of London know therefore they have only a few months left to get the definitive image.

Fortunately, Cassini will spend its remaining time flying close in to the planet and the moonlet's place in the so called A-ring.

The best ever chance to see the face of Peggy is now at hand.

And such is the fondness for this little object, the probe will even be commanded to take one last picture just before the big plunge.

"Peggy is such an interesting object, and for people who work on the mission and even with the public - it's captured their imagination. It's like an old friend to us, and so as you say goodbye you'd like to get a picture. Peggy will be one of the last targets for Cassini," Prof Murray told BBC News.

Theory suggests some of Saturn's bigger moons could even have been made in the rings

The study of objects like Peggy goes to the core objectives of the multi-billion-dollar international space mission.

The wide band of ice and dust that surrounds Saturn is a version in miniature of the kind of discs we see circling far-off new stars.

It is in those discs that planets form, and so seeing the processes and behaviours that give rise to objects like Peggy delivers an insight into how new worlds come into being. It is a model even for how our own Solar System was created.

"Peggy is evolving. It's orbit is changing with time," explained Prof Murray. "Sometimes it moves out, sometimes it moves in, by just a few kilometres. And this is what we think happens with proto-planets in those astrophysical discs. They interact with other proto-planets and the material in the disc, and they migrate; they move. We see that when we look at exoplanets around other stars: some can’t possibly have formed in the places we detect them now; they must have migrated at some point."

Peggy was discovered by accident. Prof Murray was using Cassini to try to image Prometheus - a bigger, very obvious moon connected with the F-ring.

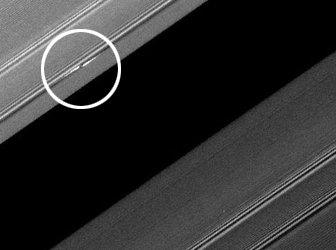

The gravitational influence of objects within the rings can produce propeller-like features

He got that no problem, but his eye was drawn to a 2,000km-long smudge in the background.

That was 15 April 2013 (his mother-in-law's birthday). And a subsequent trawl through the Cassini archive revealed that a disturbance in the A-ring was actually evident from a year before.

Peggy is certainly smaller than 5km across. So to produce that showy smudge, it must have been involved in a collision that kicked up a cloud of ice and dust.

Follow-up observations have monitored the ongoing disturbance. If moonlets are big enough they can clear a gap in Saturn’s rings. But tiny objects like Peggy merely produce small bumps in the surrounding band of particles, or a sort of wavy pattern that looks akin to a propeller.

This indirect evidence of the presence of a moonlet is all Cassini can achieve when the target is so small and the onboard camera is producing a best resolution of about 5km per pixel. But in the next few months, the orbits the spacecraft will fly around Saturn should bring the resolution down to one or two km per pixel.

This might be enough to picture Peggy directly, and to confirm an intriguing possibility… that Peggy has recently become two objects.

"When Cassini came out of its ring plane orbit in early 2016, we went back to look where Peggy should be; and we found Peggy and we've been tracking it ever since.

"But a few degrees behind we could also see another object, even fainter in the sense that it had an even smaller (disturbance) signature. And when we tracked back the paths of both objects, we realised that in early 2015 they would have met.

"So, probably, Peggy 'B', as we call it, came from a collision of the sort that causes Peggy to change its orbit, but rather than a simple encounter that deflected the orbit slightly, this was more serious."

Linda Spilker: "Cassini is one of the great space missions of all time"

Prof Murray gave an update on Peggy at the recent Fall Meeting of the American Geophysical Union, external. At that same conference, Dr Linda Spilker, the Nasa project scientist on the Cassini mission, outlined the end-stage activities, external of the probe, culminating in its disposal on 15 September.

She said the same close-in manoeuvres that hopefully will enable Carl Murray to get his resolved pictures should also finally help to determine a key property of Saturn's rings - their mass.

"The mass of the rings is uncertain by 100%," Dr Spilker told BBC News.

"If they're more massive, maybe they're really old - as old as Saturn. If they're less massive, maybe they're really young, maybe only a mere 100 million years old."

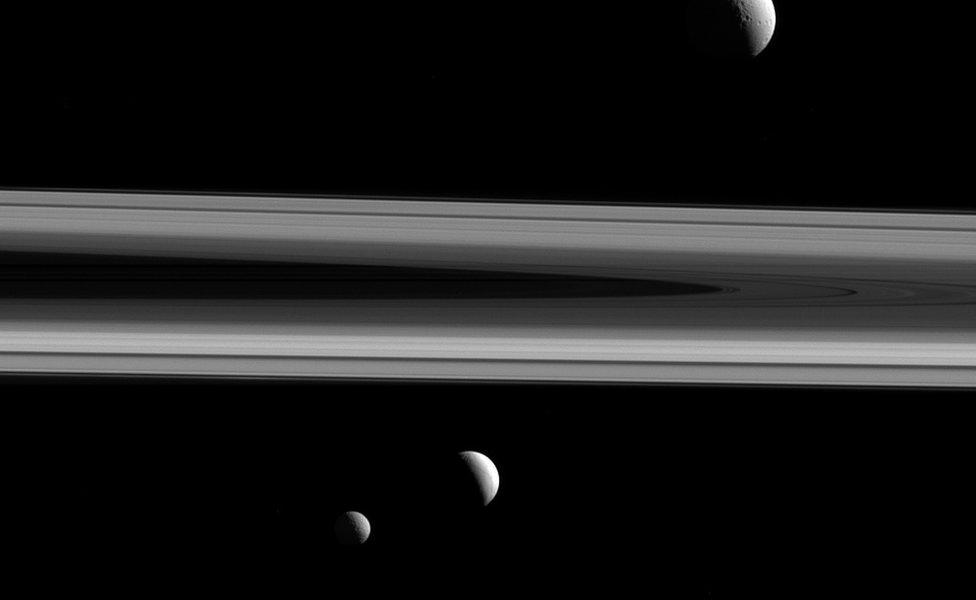

Age is important to this idea that rings, or discs, are the medium in which objects form. Some of Saturn's moons, even a number of its bigger ones, likely emerged by accumulating the material around them and displaying, certainly in the early phases of growth, the sorts of behaviours now seen in Peggy.

But making moons takes time and if the largest of Saturn's satellites came out of this same process, it demands the present ring system to be very old indeed.

Want to hear more about Cassini and its discoveries at Saturn? Listen to this week's The Life Scientific, which featured Imperial College London's Prof Michele Dougherty, the principal investigator on the spacecraft's magnetometer instrument.