Concerns over first snow and common leopards found in same area

- Published

Already endangered, the snow leopard may face further pressure

The first ever recorded video footage showing snow leopards and common leopards sharing the same habitat on the Tibetan plateau has caused concern among conservationists.

They are worried about the future of the snow leopard's habitat if common leopards begin to live at higher elevations in a warming climate.

The issue will be high on the agenda of an international meeting involving 12 snow leopard range countries starting in Nepal on Tuesday, 17 January.

The video was recently obtained from a camera trap in Qinghai province in China. It shows both cats at the same location in July 2016.

Wildlife experts say this is the first pictorial evidence of the two cats at the same place. The snow leopard is an endangered species.

One of the video clips from the camera trap shows a female common leopard with a cub.

Climate change could help common leopards expand their range

This has made researchers think that the animal was not simply visiting the area but was actually living there.

Under threat

Snow leopards live at an altitude above 3,000m in typically open and rocky areas.

Common leopards' habitats include forests and woodlands at lower elevations.

Snow leopards are sparsely distributed across 12 countries - Mongolia and the Himalayan ranges in China, Afghanistan, Pakistan, India, Nepal and Bhutan, as well as in the five Central Asian states.

There are an estimated 3,500 to 7,000 snow leopards in the wild and they have been listed as endangered mainly because of poaching and habitat loss.

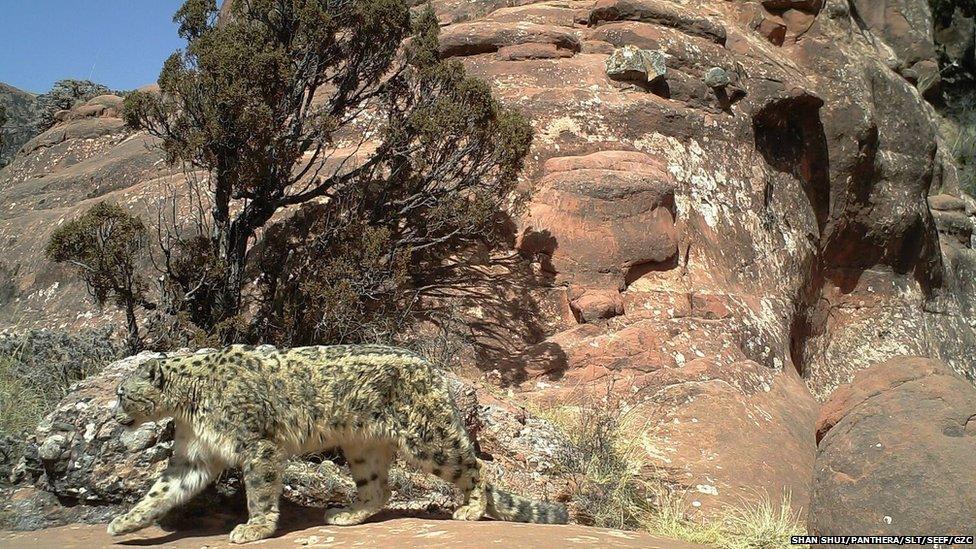

A snow leopard photographed in Qinghai province, China on 10 January 2016.

Scientists say the lower reaches of snow leopard's habitats and the upper limits of common leopards' territories have always overlapped in the Himalayas and other high mountains in Asia.

But, they add, climate change could make that more complicated.

"In a changing climate, we expect the tree line to move up the slopes and that's encroaching into the snow leopard's habitat," said Byron Weckworth, China programme director with Panthera, a conservation organisation dedicated to preserving wild cats.

Some studies have shown that the upper forest tree line is already being pushed higher.

They suggest that between 30% and 50% of the current snow leopard habitat in the Himalayas will be lost because of the shifting tree line and the shrinking of the alpine zone.

"The bigger threat is the snow leopards' habitat loss and its fragmentation," said Mr Weckworth, whose organisation has partnered with the Snow Leopard Trust and Chinese conservation organisation Shan Shui to monitor wildlife in China's Sanjiangyuan nature reserve.

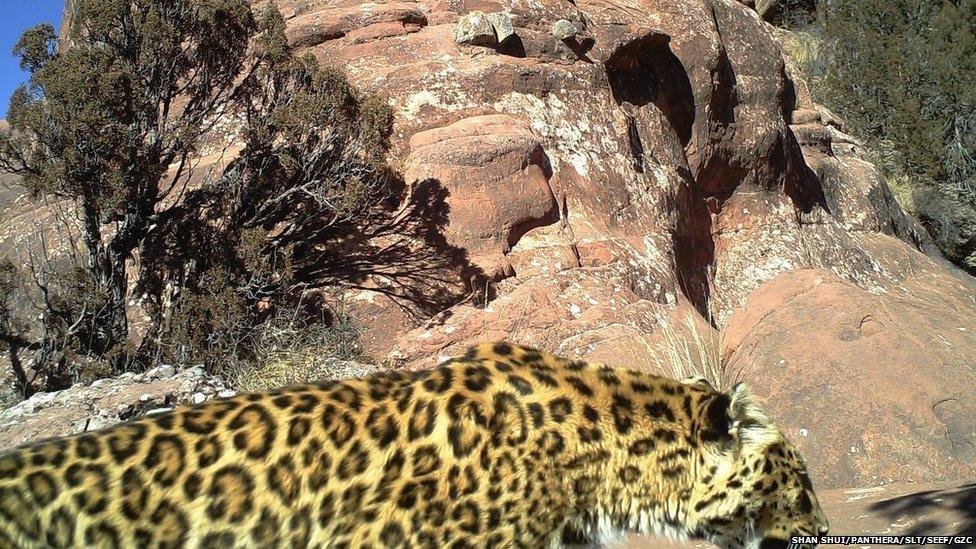

A common leopard photographed in the same location in Qinghai province, China on 16 March 2016. This is the traditional habitat of the snow leopard

Prof Sandro Lovari, from the University of Siena in Italy, was not involved in this research but has conducted separate studies on snow leopards.

He agrees with the loss of habitat projections.

"Snow leopards could be squeezed between the barren land of the higher parts of the mountain and the upward moving tree line," he said.

Wen Cheng from Shan Shui says the availability of food will be key.

"The possibility for co-existence or conflict highly depends on the abundance and diversity of wild prey," he said.

Prof Lovari's team conducted a study on snow leopards in the Sagarmatha National park in Nepal's Everest region in 2013.

They found that the common leopard had a greater habitat adaptability.

"This behaviour could enhance the [common leopard's] takeover of the snow leopard's habitat as it's the larger, more ecologically flexible species," Prof Lovari explained.

In Nepal's Annapurna and Kanchanjunga conservation areas too, common leopards have been recently found in altitudes that normally have been the territories of snow leopards.

Koustubh Sharma, an expert with the Snow Leopard Trust, said: "How are these two cat species already managing to live together - or will the interface be difficult when their habitats are changing with climate change?"

"The pictures from our camera trap make these questions more relevant and pressing."

While some conservationists fear that there might be conflicts between the two leopard species for habitat and prey, others think the two already co-exist in places where their territories overlap.

Mr Weckworth said their research team in China found locals believing that the two species could even mate.

"The common leopards there are more pale in colour and that may have sparked that kind of perception among locals. But from a biological point of view, it's extremely unlikely that they can hybridise," Mr Weckworth of the Panthera organisation added.

During his field study in Nepal's Sagarmatha National Park, Prof Lovari said he found male snow leopards coming down to the edge of the forested land during the mating period.

"But there is no information whatsoever on the hybridisation between common and snow leopards," he said.

"It would be very unlikely - even more unlikely than brown bears and polar bears."