New mercury threat to oceans from climate change

- Published

There have been concerns over the levels of mercury in fish for many years

Rising temperatures could boost mercury levels in fish by up to seven times the current rates, say Swedish researchers.

They've discovered a new way in which warming increases levels of the toxin in sea creatures.

In experiments, they found that extra rainfall drives up the amount of organic material flowing into the seas.

This alters the food chain, adding another layer of complex organisms which boosts the concentrations of mercury up the line.

The study has been published, external in the journal, Science Advances.

Toxic form

Mercury is one of the world's most toxic metals, external, and according to the World Health Organization, is one of the top ten threats to public health. The substance at high levels has been linked to damage to the nervous system, paralysis and mental impairment in children.

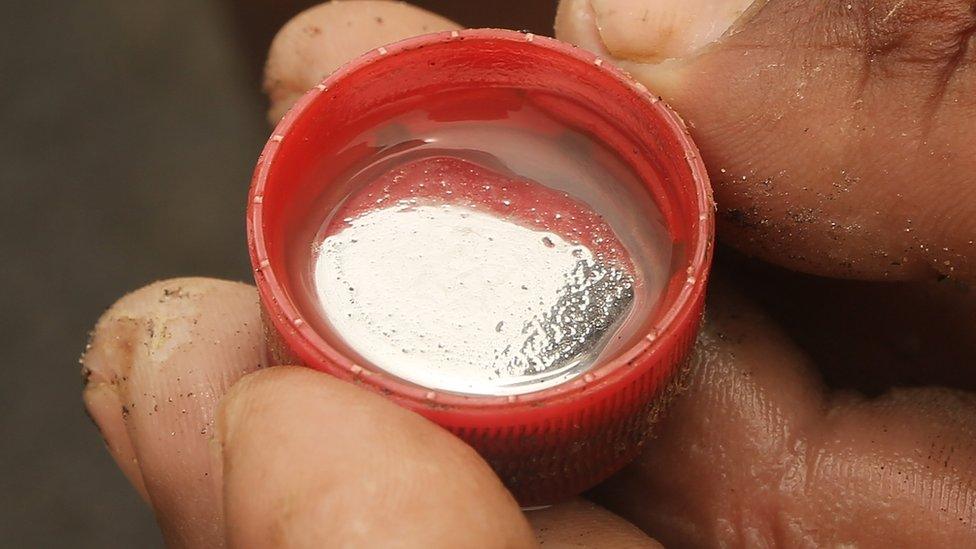

Mercury is used in many parts of the world especially in gold mining

The most common form of exposure to mercury is by eating fish containing methylmercury, an organic form of the chemical which forms when bacteria react with mercury in water, soil or plants.

Levels of mercury in the world's ecosystems have increased by between 200 and 500%, since the industrial revolution say experts, driven up by the use of fossil fuels such as coal.

In recent years there are have been concentrated efforts to limit the amount of mercury entering the environment, with an international treaty, called the Minamata Convention, signed by 136 countries, external in place since 2013.

Researcher Erik Bjorn injects mercury into sediment samples

But this new study suggests that climate change could be driving up levels of methylmercury in a manner not previously recognised.

In a large laboratory, Swedish researchers recreated the conditions found in the Bothnian sea estuary. They discovered that as temperatures increase, there is an increased run-off of organic matter into the world's oceans and lakes. This encourages the growth of bacteria at the expense of phytoplankton.

"When bacteria become abundant in the water there is also a growth of a new type of predators that feed on bacteria," lead author Dr Erik Bjorn from Umea University in Sweden told BBC News.

"You basically get one extra step in the food chain and methylmercury is enriched by about a factor of ten in each such step in the food web."

Under the warmest climate scenario suggested by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, there would be an increase in organic matter run-off of 15-20% by the end of this century. This in turn would see levels of methylmercury in zooplankton, the bottom link in the food chain, grow by between two and seven fold.

Sediment cores were recovered from Swedish coastal waters for use in the mercury experiments

Different parts of the world will suffer different impacts say the researchers, with lakes and coastal waters in the northern hemisphere being the most likely to have significant increases in methylmercury levels in fish, while the Mediterranean, the central US and Southern Africa will likely see reductions.

Researchers hope that the Minamata treaty will be successful and countries reduce the amount of mercury that is being produced. Otherwise this discovery of a previously unknown source could have impacts for human health.

"If we reduce mercury emissions, then we need to know how fast will ecosystems recover," said Dr Bjorn.

"If we don't do anything and mercury doesn't decrease, and we add this on top then the implications would be severe."

Other researchers in the field say that the new study highlights important issues that have previously been little known.

"This work experimentally proves that climate change will have a significant effect of methylmercury budgets in coastal waters and its concentrations in fish," said Milena Horvat from the Jozef Stefan Institute in Slovenia.

"This work will also have an important impact on future scenario simulations on the presence of mercury in fish in response to global mercury reductions from emission sources (primarily industrial)."

Follow Matt on Twitter, external and on Facebook, external