Star's seven Earth-sized worlds set record

- Published

All seven planets are thought to have Earth-like characteristics (Photo credit: Nature)

Astronomers have detected a record seven Earth-sized planets orbiting a single star.

The researchers say that all seven could potentially support liquid water on the surface, depending on the other properties of those planets.

But only three are within the conventional "habitable" zone where life is considered a possibility.

The compact system of exoplanets orbits Trappist-1, external, a low-mass, cool star located 40 light-years away from Earth.

The planets, detected using Nasa's Spitzer Space Telescope and several ground-based observatories, are described in the journal Nature, external.

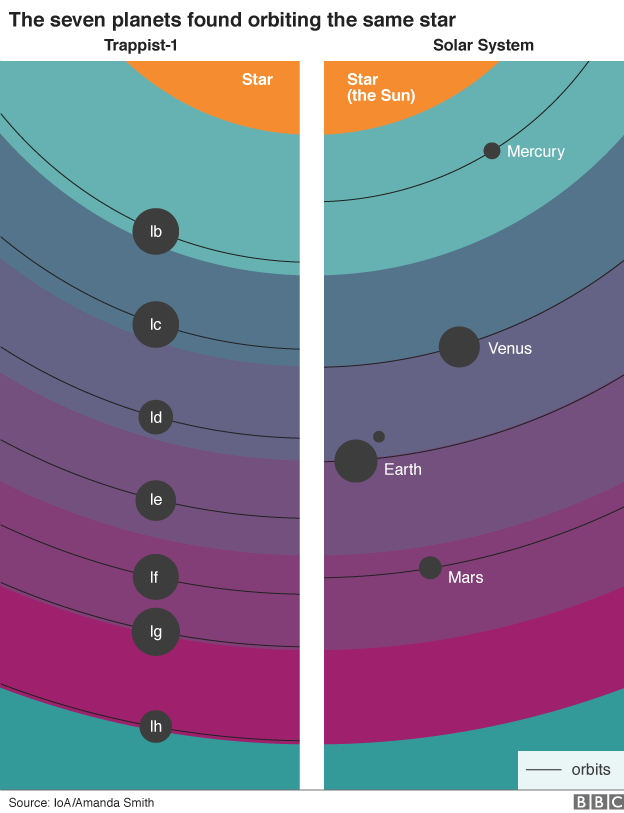

The graphic compares the heat (coloured bands) received by the planets in the Trappist-1 system and our Solar System. In Trappist-1, although the planets are much closer to the star, this star is smaller and cooler than our Sun

Lead author Michaël Gillon, from Belgium's University of Liège, said: "The planets are all close to each other and very close to the star, which is very reminiscent of the moons around Jupiter."

"Still, the star is so small and cold that the seven planets are temperate, which means that they could have some liquid water - and maybe life, by extension - on the surface."

Co-author Amaury Triaud, from the University of Cambridge, UK, said the team had introduced the "temperate" definition to broaden perceptions about habitability.

Artwork: It's possible that some or all of the planets could host liquid water

Three of the Trappist-1 planets fall within the traditional habitable zone definition, where surface temperatures could support the presence of liquid water - given sufficient atmospheric pressure.

But Dr Triaud said that if the planet furthest from the parent star, Trappist-1h, had an atmosphere that efficiently trapped heat - a bit more like Venus's atmosphere than Earth's - it might be habitable.

"It would be disappointing if Earth represents the only template for habitability in the Universe," he told the BBC News website.

Analysis - David Shukman, BBC Science Editor

So many planets have been discovered in planetary systems beyond our own that it's easy to become inured to their potential significance. Nasa's latest tally is an impressive 3,449 and there's a danger of hype with each new announcement.

But the excitement around this latest discovery is not only because of its unusual scale or the fact that so many of the planets are Earth-sized. It is also because the star Trappist-1 is conveniently small and dim. This means that telescopes studying the planets are not dazzled as they would be when aiming at far brighter stars.

In turn that opens up a fascinating avenue of research into these distant worlds and, above all, their atmospheres.

The next phase of research has already started to hunt for key gases like oxygen and methane which could provide evidence about whatever is happening on the surface.

Coverage of exoplanets can far too easily leap to conclusions about alien life. But this remote planetary system does provide a good chance to look for clues about it.

The six inner planets have orbital periods that are organised in a "near-resonant chain". This means that in the time that it takes for the innermost planet to make eight orbits, the second, third and fourth planets revolve five, three and two times around the star, respectively.

This appears to be an outcome of interactions early in the evolution of the planetary system.

The astronomers say it should be possible to study the planets' atmospheric properties with telescopes.

"The James Webb Space Telescope, Hubble's successor, will have the possibility to detect the signature of ozone if this molecule is present in the atmosphere of one of these planets," said co-author Prof Brice-Olivier Demory, from the University of Bern in Switzerland.

"This could be an indicator for biological activity on the planet."

Nasa has produced a "travel poster" for the system

But the astrophysicist also warns that we must remain extremely careful about inferring biological activity from afar.

Some of the properties of cool, low mass stars could make life a more challenging prospect. For example, some are known to emit large amounts of radiation in the form of flares, which has the potential to sterilise the surfaces of nearby planets.

In addition, the habitable zone is located closer to the star so that planets receive the heating necessary for liquid water to persist. But this causes a phenomenon called tidal locking, so that planets always show the same face to their star.

This might have the effect of making one side of the planet hot, and the other cold.

But Amaury Triaud said UV light might be vital for producing the chemical compounds that can later be assembled into biological systems. Similarly, if life emerges on the permanent night side of a tidally locked planet, it might be sheltered from any flares.

But he said the Trappist-1 star was not particularly active, something it has in common with other "ultra cool dwarfs" the team has surveyed.

"It is fair to say there is much we don't know. Where I am hopeful is that we will know if flares are important, we will know if tidal locking is relevant to habitability and maybe to the emergence of biology," he explained.

"Many of the arguments in favour or disfavour of habitability can be flipped in that way. First and foremost we need observations."

In addition to the Spitzer observations, astronomers gathered data using Very Large Telescope in Chile, the Liverpool Telescope in La Palma, Spain, and others.

Follow Paul on Twitter., external