Huge Large Hadron Collider experiment gets 'heart transplant'

- Published

Replacing the CMS's pixel detector should help scientists search for signs of new physics

One of the Large Hadron Collider's huge experiments has been given what's described as a "heart transplant".

Officials said the replacement of a key component inside the CMS experiment represented the first major upgrade to the LHC - the world's biggest machine.

Engineers have been carefully installing the new "pixel tracker" in CMS in a complex and delicate procedure on Thursday 100m underground.

It should boost the hunt for signs of new physics phenomena.

The LHC is a particle accelerator that pushes two particle beams to near the speed of light and smashes them together so that scientists can look for signs of new physics phenomena in the debris - including new sub-atomic particles.

More than 1,200 "dipole" magnets steer the beam around a 27km-long circular tunnel under the French-Swiss border. At certain points around the ring, the beams cross, allowing collisions to take place. Large experiments like CMS and Atlas then record the outcomes of these encounters, generating more than 10 million gigabytes of data every year.

The CMS (Compact Muon Solenoid) pixel tracker is designed to disentangle and reconstruct the paths of particles emerging from the collision wreckage.

"It's like substituting a 66 megapixel camera with a 124 megapixel camera," Austin Ball, technical co-ordinator for the CMS experiment, told BBC News.

In simple terms, the pixel detector takes images of particles which are superimposed on top of one another, and then need to be separated.

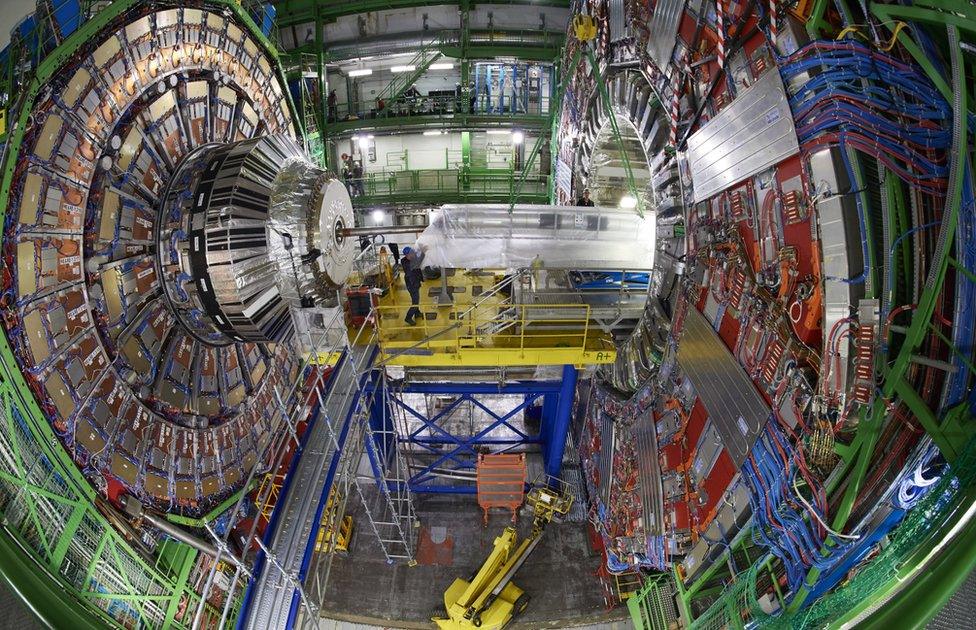

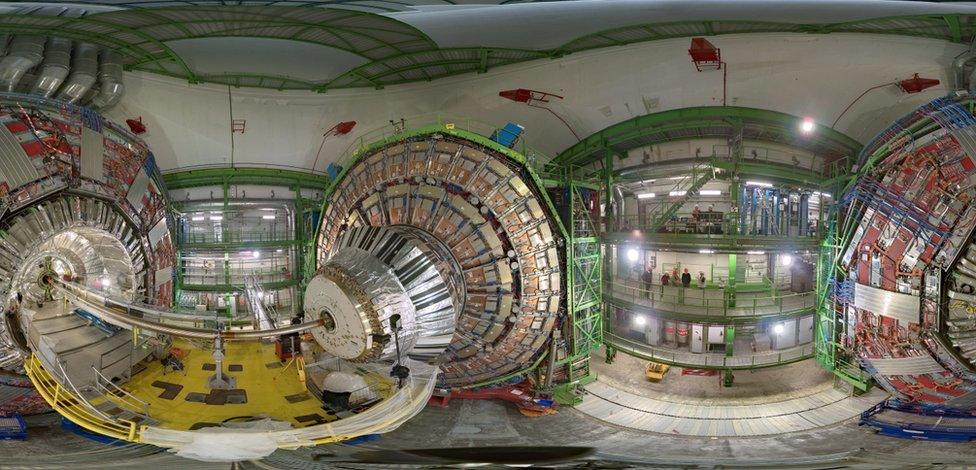

The structure of CMS has been pulled apart to allow access to its "heart"

The complexity of the operation means it has been taking place in stages

As the LHC's performance has been boosted in the past few years, "rather than having 25 or 30 protons collide with each other, yielding 25 or 30 superimposed pictures, we're now expecting to have to deal with 50 or 60 superimposed pictures", said Mr Ball. This required a "step up" in technology, he explained.

"There are limits to the camera analogy - it's a 3D imaging system. But the point is that the new system is more powerful at disentangling the effects of having multiple collisions superimposed on top of each other," the CMS technical co-ordinator said.

"We were looking ahead when we decided to build this device and install it now. But as it turns out, the performance of the accelerator has improved so rapidly over the past couple of years that this is the time we need to make the change to exploit the accelerator's full potential - for new physics, and the study of existing physics."

Engineers began pulling apart the experiment's structure just before Christmas, when the LHC shuts down for the winter. A delicate and painstaking process, it took the team until last week to be in a position to replace the pixel detector. It also allows for some spectacular views of the technology that makes up CMS.

One half of the pixel detector was installed on Tuesday. On Thursday morning, the second half of the device - which weighs a few tens of kilos - left its cleanroom to be picked up by a crane and lowered 100m into the cavern hewn out of the local Molasse sandstone to house the CMS experiment.

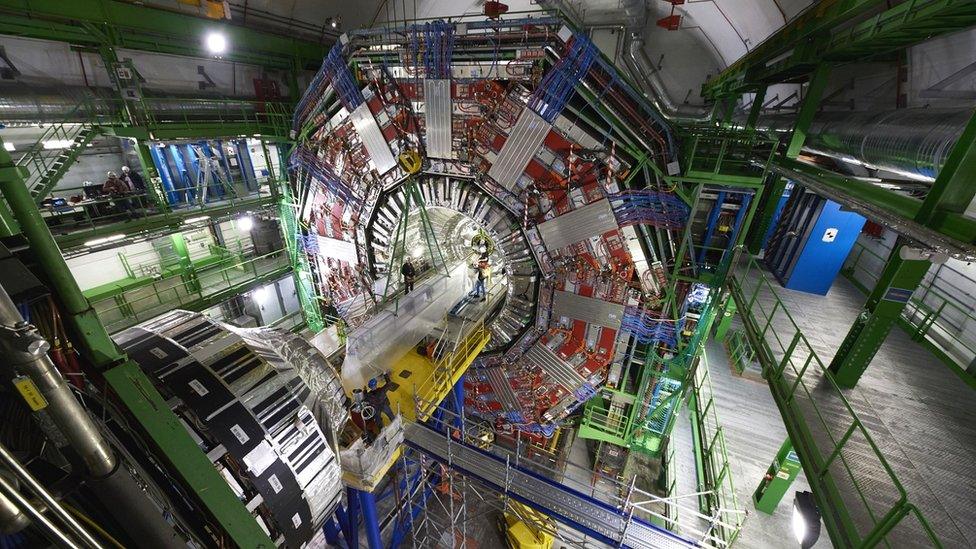

CMS is one of two "multi-purpose" experiments recording collision data at the LHC

At the bottom, it was placed on a platform with slide mechanisms that allow access to the central part of CMS. At around 09:00 GMT (10;00 local time), engineers began the roughly hour-long process of inserting the hardware into its final location inside the experiment. After that, engineers connect the cooling system that keeps the detector at its operating temperature below -10C.

CMS and its counterpart Atlas are the two "multi-purpose" experiments at the LHC. Staffed by separate - and competing - teams of physicists, they provided the crucial evidence that led to the discovery of the elusive Higgs boson, announced in 2012.

The Higgs was the last major jigsaw piece in the theory of particle physics known as the Standard Model (SM). But the hoped-for signs of physical phenomena beyond the Standard Model, such as evidence for dark matter or supersymmetry - a theorised extension to the SM which invokes a range of new sub-atomic particles - have taken longer than expected to reveal themselves at the LHC.

The change to CMS should help physicists in that endeavour, said Mr Ball: "We have to make sure that our detectors can keep up with what's being thrown at them... we're trying to access rarer processes, and to do that you need to produce and record more collisions between protons."

"Very often, only slight deviations from theoretical predictions are the clues to new things we should be looking for."

Follow Paul on Twitter., external