Kaikoura: 'Most complex quake ever studied'

- Published

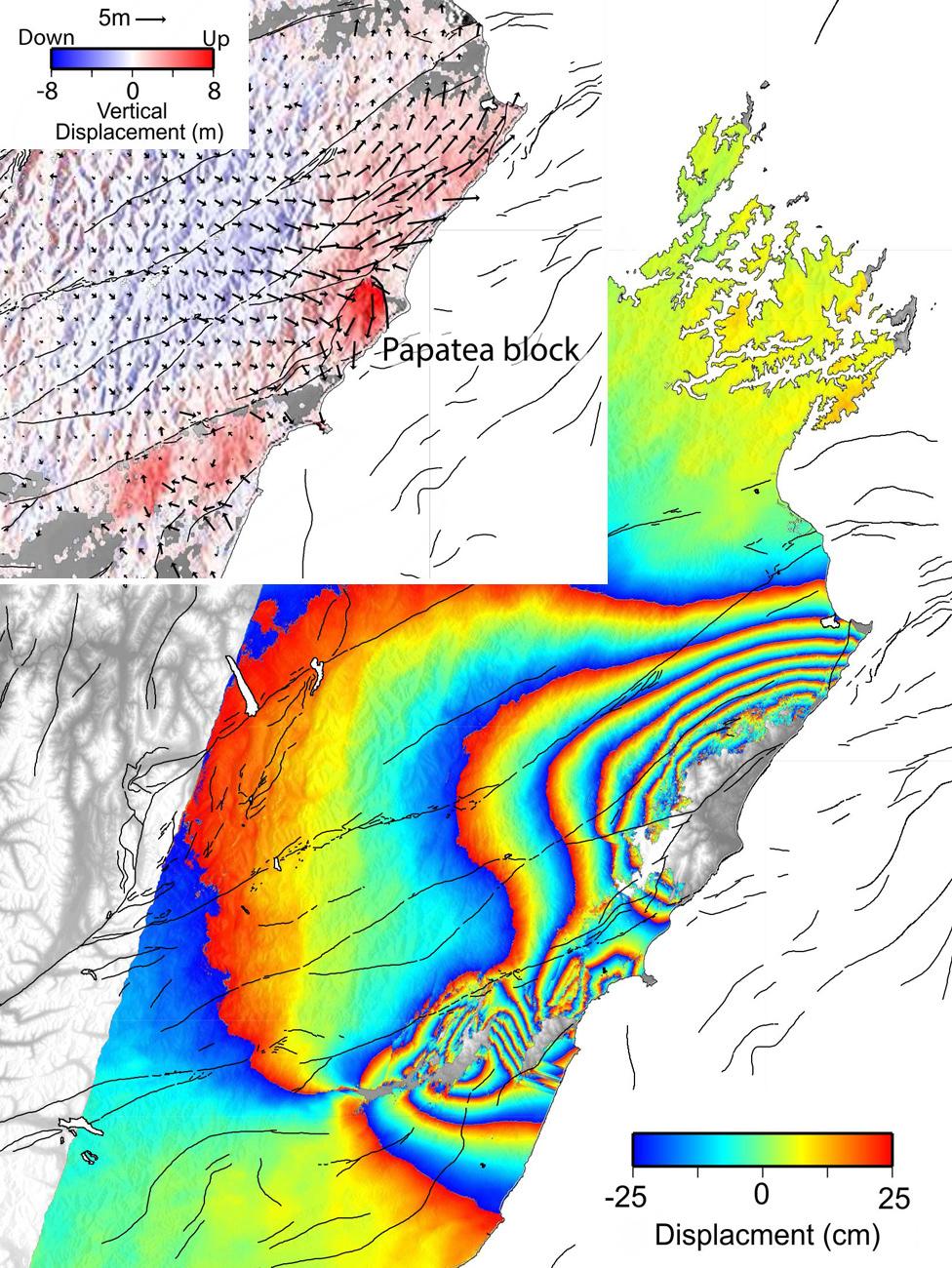

New wall: Whole blocks of ground were lifted upwards

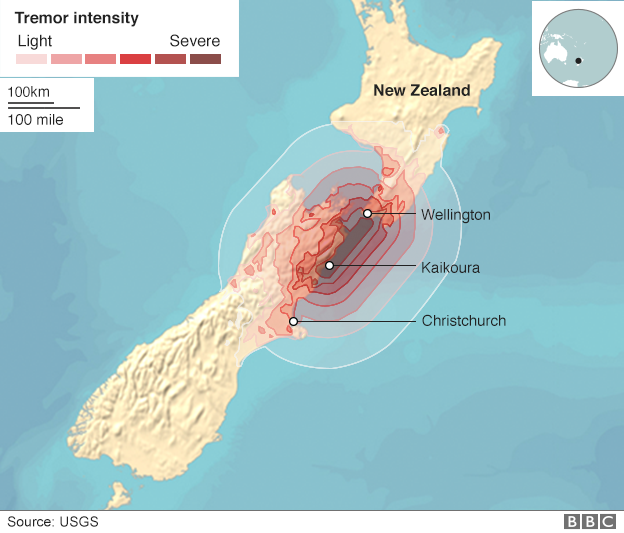

The big earthquake that struck New Zealand last year may have been the most complex ever, say scientists.

November's Magnitude 7.8 event ruptured a near-200km-long swathe of territory, shifting parts of the South Island 5m closer to the North Island.

Whole blocks of ground were buckled and lifted upwards, in places by up to 8m.

Subsequent investigations have found that at least 12 separate faults broke during the quake, including some that had not previously been mapped.

Writing up its findings in the journal Science, external, an international team says the Kaikoura event, as it has become known, should prompt a rethink about how earthquakes are expected to behave in high-risk regions such as New Zealand.

"What we saw was a scenario that would never have been included in our seismic hazard models," said Dr Ian Hamling from the country's geophysics research agency, GNS Science, external.

Drone footage of the Papatea fault crossing State Highway 1

At issue was the way the quake was able to rupture so far along its path, to produce such a big magnitude.

Starting in the South Island's North Canterbury region, the crustal failure moved eastwards and northwards along the coast to Marlborough Province, before then petering out offshore. In the process, the quake managed to straddle two major fault networks.

The behaviour challenged some long-accepted ideas. One of these is the notion that ruptures cannot jump large separations between individual fault segments.

Five km is considered something of a limit. But in the Kaikoura event, substantially larger step-overs were recorded.

How this was possible is not fully explained, says Prof Tim Wright from Leeds University, UK, external.

"We think the main reason was some very large stress changes introduced early in the earthquake that then triggered the later segments to fail," he told the Science In Action programme on the BBC World Service.

"There were also in this case some faults we didn't know about, even though New Zealand has one of the best fault maps in the world; and so some of these big jumps were facilitated by motion on faults we didn't know were there. But in many cases, there are genuine gaps of 15-20km."

Prof Tim Wright: "The Kaikoura quake broke the rules"

The team believes the exceptional nature of the Kaikoura event raises questions about how the risk of future quakes is assessed. Some of the assumptions that go into building seismic models now need to be revisited, the group argues.

In terms of magnitude, only December's M7.9 event in Papua New Guinea was bigger in 2016. Given the level of shaking produced in the New Zeland quake, it is remarkable there were so few deaths ("just" two) and injuries. Hundreds of people in the town of Kaikoura itself did though have to be evacuated because landslides had cut local roads.

Also astonishing was the scale of "surface expression". Giant fissures opened in the ground, highways were broken by metres-long offsets, beaches rose up from the sea, and railway lines were lifted high into the air.

Walking the faults: Multiple techniques are used to study quakes - on the ground and from space

One of the most photographed areas was the countryside around the Papatea fault.

"You can call it bonkers; it's certainly a real puzzle," said Dr Hamling. "It's a block of material of about 50 sq km that's been thrust up out of the ground by about 8m and then pushed south by 4-5m.

"To try to model it in the traditional way is almost impossible; it's very hard to explain how you can get this thing to pop up in the manner that it has."

Earthquakes can be studied using satellite radar images. They will trace the amount of ground movement. In the Kaikoura event, parts of northern South Island moved by about 6m horizontally with an uplift of about 8m

To understand the complexity of the Kaikoura quake, the scientists used a range of techniques, including mapping with satellite interferometry.

This works by finding the difference in "before" and "after" radar images of the Earth taken from orbit. It allows even quite subtle ground movements to be detected, including in those areas where the surface itself has not been ripped apart.

The team was able to call on two different systems - the Sentinel-1 spacecraft operated by Europe, and the Alos platform owned by the Japanese.

"Alos's longer radar wavelengths allow us to see through the vegetation; we can see the tree trunks rather than the leaves and they're much more stable for making deformation maps," explained Prof Wright.

"However, with Sentinel's shorter wavelengths you get much more detail, which allows us to narrow down exactly where the deformation has occurred."

Three cows left stranded by the quake became an internet sensation

Jonathan.Amos-INTERNET@bbc.co.uk, external and follow me on Twitter: @BBCAmos, external