Why a tiny, fanged fish produces a pain-free bite

- Published

Research reveals the toxic secret of the fang blenny's pain-free bite

Venom research laboratory scientists have solved the mystery of the pain-free bite from a small, fanged fish.

Researchers found that the fang blenny, a reef-dwelling fish, administers a bite that is laced with opioids.

These morphine-like compounds cause a sudden drop in blood pressure, apparently disorientating a predator and letting the blenny escape.

The findings, published in Current Biology,, external are an example of medical secrets still hidden in our oceans.

Scientists from the Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine and the University of Queensland in Australia became interested in these small, brightly coloured fish because their pain-free bite was so unusual in the marine world.

Bryan Fry, from the University of Queensland, explained that fish with venomous spines on their bodies "produce immediate and blinding pain".

"The most pain I've ever been in other than the time I broke my back was from a stingray envenomation," he said, describing the experience as "pure hell".

This made the fang blenny a curiosity; the scientists knew it to be venomous, but set out to understand how and why its bite was painless.

As Dr Nicholas Casewell, from the Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine, pointed out, a painful sting or bite is a useful defence mechanism - "predators learn to avoid it".

Jaws of death

In his initial research, Dr Casewell read fang blenny studies carried out in the 1970s, where larger, predatory fish were "introduced" to the fang blennies.

"They took the fang blennies into their mouths, then quickly started quivering and opened their mouths again," Dr Casewell described. "The fang blenny would simply swim out of the mouth and escape."

Examining the make-up of the venom revealed the diminutive fish's super-power - opioids.

This group of chemicals, which includes morphine and codeine, have well-known pain-subduing effects, but they also cause a drop in blood pressure.

That would cause us to feel faint and dizzy, explained Dr Casewell.

"And the drop seems to cause a loss of co-ordination in the predator that allows the blenny to get away."

Hidden treasures

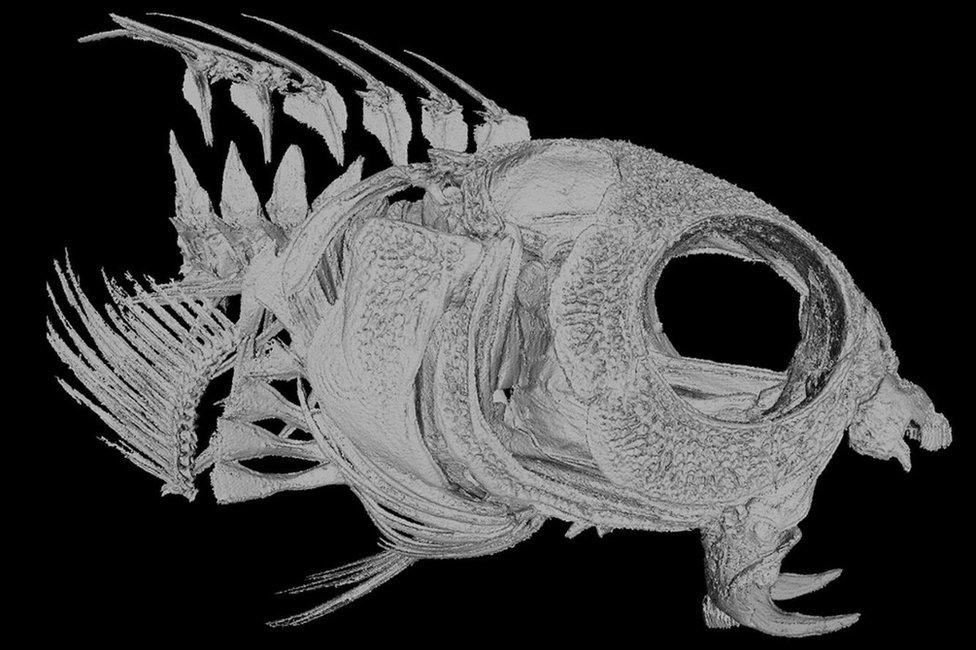

The researchers scanned fang blennies, revealing their venom glands

In the biodiverse realm of coral reefs, other species also "mimic" the fang blenny - developing similar striped patterns and bright colours that may fool predators into thinking that they too are opioid-laced.

And while the team does not expect to develop new pain medications based on this discovery, Dr Casewell said it revealed just how much is still hidden in coral reefs, which are under threat around the world as sea temperatures rise.

"We risk decimating species that could have something in them that could be harnessed for human benefit," Dr Casewell told BBC News.

"We could be destroying that resource before we even have the chance to find it."

Dr Robert Harrison from the Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine explains how milking the venom from deadly snakes could save lives

John Bythell, professor of coral reef biology at Newcastle University, agreed that there were "absolutely vast undiscovered natural products in coral reefs that will prove to be beneficial to humans... we have barely begun to scratch the surface".

"Think about how much is still to be learnt about the human genome (given all the resources we have thrown at it), since it was sequenced in 2003, then multiply that up by several million species in the reef environment, it gives some idea," Prof Bythell told BBC News.

"I think the intrinsic value of biodiversity is that we cannot understand how it may be used or what it will mean for future generations, but once it is gone it is gone."

- Published31 March 2017

- Published21 March 2017

- Published9 January 2015

- Published8 October 2015