Is consciousness just an illusion?

- Published

Is the human brain really just a collection of complex machines?

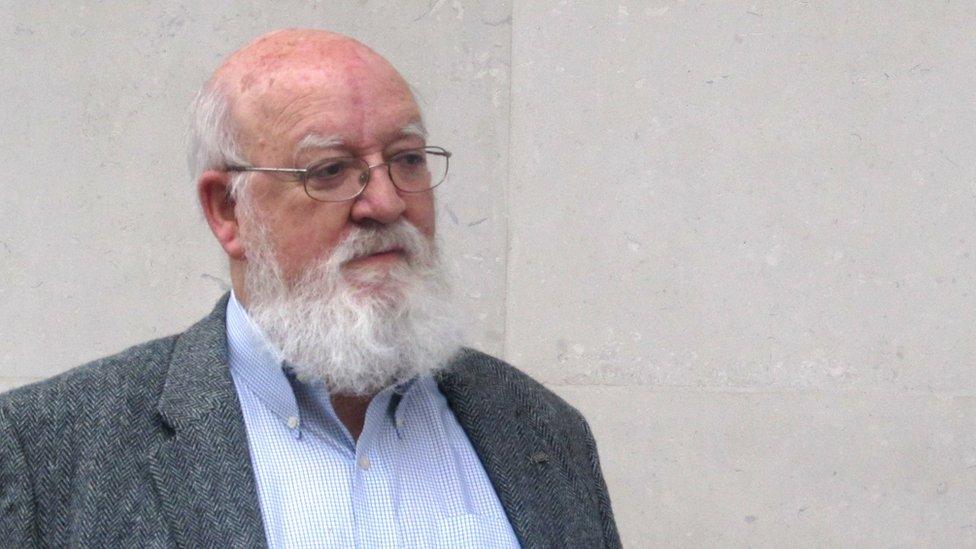

The cognitive scientist Daniel Dennett believes our brains are machines, made of billions of tiny "robots" - our neurons, or brain cells. Is the human mind really that special?

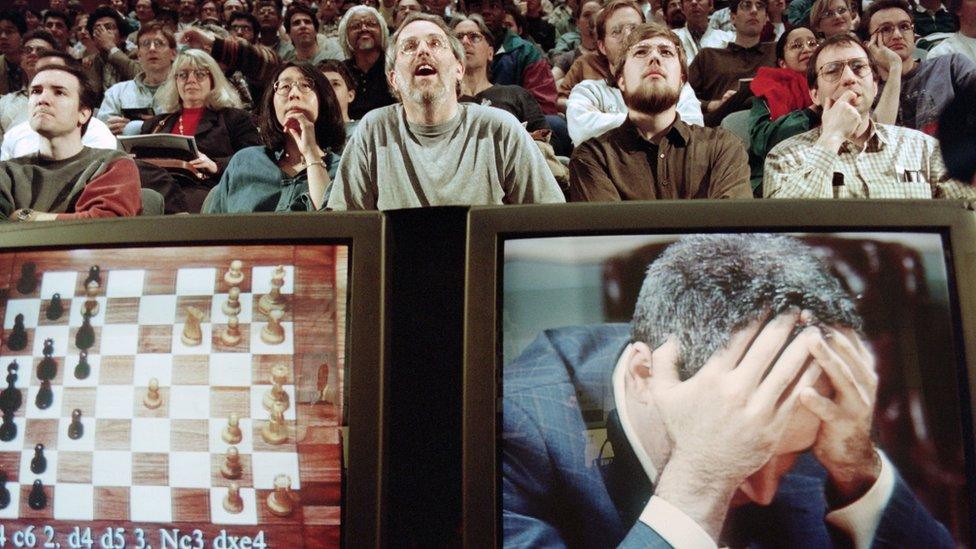

In an infamous memo written in 1965, the philosopher Hubert Dreyfus stated that humans would always beat computers at chess because machines lacked intuition. Daniel Dennett disagreed.

A few years later, Dreyfus rather embarrassingly found himself in checkmate against a computer.

And in May 1997 the IBM computer, Deep Blue defeated the world chess champion Garry Kasparov.

Many who were unhappy with this result then claimed that chess was a boringly logical game. Computers didn't need intuition to win. The goalposts shifted.

Daniel Dennett has always believed our minds are machines. For him the question is not can computers be human? But are humans really that clever?

In an interview with BBC Radio 4's The Life Scientific, Dennett says there's nothing special about intuition. "Intuition is simply knowing something without knowing how you got there".

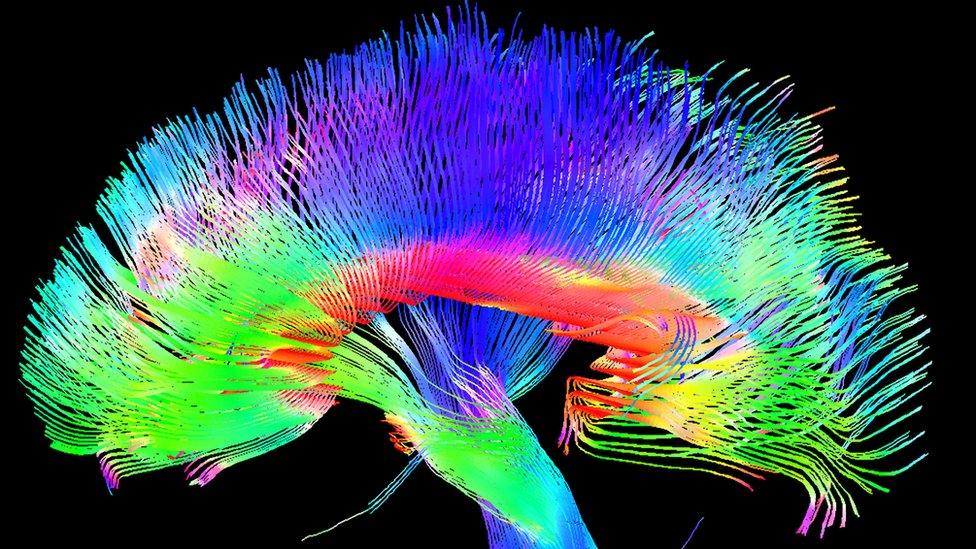

Daniel Dennett believes our brain cells are "robots" responding to chemical signals

Dennett blames the philosopher Rene Descartes for permanently polluting our thinking about how we think about the human mind.

Descartes couldn't imagine how a machine could be capable of thinking, feeling and imagining. Such talents must be God-given. He was writing in the 17th century, when machines were made of levers and pulleys not CPUs and RAM, so perhaps we can forgive him.

Robots made of robots

Our brains are made of a hundred billion neurons.

If you were to count all the neurons in your brain at a rate of one a second, it would take more than 3,000 years.

Our minds are made of molecular machines, otherwise known as brain cells. And if you find this depressing then you lack imagination, says Dennett.

People were shocked when a computer beat chess champion Garry Kasparov in 1997

"Do you know the power of a machine made of a trillion moving parts?", he asks.

"We're not just are robots", he says. "We're robots, made of robots, made of robots".

Our brain cells are robots that respond to chemical signals. The motor proteins they create are robots. And so it goes on.

Like a phone screen

Consciousness is real. Of course it is. We experience it every day. But for Daniel Dennett, consciousness is no more real than the screen on your laptop or your phone.

The geeks who make electronic devices call what we see on our screens the "user illusion". It's a bit patronising, perhaps, but they've got a point.

Pressing icons on our phones makes us feel in control. We feel in charge of the hardware inside. But what we do with our fingers on our phones is a rather pathetic contribution to the sum total of phone activity. And, of course, it tells us absolutely nothing about how they work.

Human consciousness is the same, says Dennett. "It's the brain's 'user illusion' of itself," he says.

It feels real and important to us but it just isn't a very big deal.

"The brain doesn't have to understand how the brain works".

Not as clever as we think

We know we evolved from apes. We know we share 99% of our DNA with chimpanzees.

We acknowledge that some of our behaviour is due to our animal nature, (albeit generally not the aspects we are most proud of). Our more special qualities, our intelligence, our insight and creativity, we like to think, must have more special causes.

We humans have traditionally emphasised our differences from the animal kingdom, but we're all just the result of evolutionary experiments

Our brains, like our bodies, have evolved over hundreds of millions of years. They are the result of millions and millions of years of haphazard trial and error evolutionary experiments.

From an evolutionary perspective, our ability to think is no different from our ability to digest, says Dennett.

Both these biological activities can be explained by Darwin's Theory of Natural Selection, often described as the survival of the fittest.

Trial and error

We evolved from uncomprehending bacteria. Our minds, with all their remarkable talents, are the result of endless biological experiments.

Our genius is not God-given. It's the result of millions of years of trial and error.

When a bacteria moves towards a food source, scientists don't praise the bacteria for being clever. That would be highly unscientific. But when scientists describe thinking as a biological activity, they risk ridicule or outrage (depending on the company they keep).

Such fierce reductionism offends. How naïve to suggest that there is nothing more to the human mind than a bunch of neurons!

Descartes grossly underestimated machines. Alan Turing set him right.

He predicted that by the end of the 20th century: "The use of words and general educated opinion will have altered so much that one will be able to speak of machines thinking without being contradicted."

Computers in the 1960s were not very good at chess. Now they play the saxophone like John Coltrane.

In this digital age of supercomputers and smart phones, surely it isn't so difficult to imagine how a machine made of a trillion moving parts might just be capable of being human.

The Life Scientific is broadcast at 09:00 BST on Tuesday 4 April on BBC Radio 4.