Poo sediments record Antarctic 'penguin Pompeii'

- Published

The perilous history of a penguin colony on a small Antarctic island has been recorded in their excrement.

For thousands of years, the birds have nested on the Ardley outcrop where their poop, or guano, would collect at the bottom of a lake.

But when scientists drilled into these sediments, they got quite a surprise.

Interspersed with the layers of penguin waste were thick sections of volcanic ash, indicating the Ardley birds were frequently decimated by eruptions.

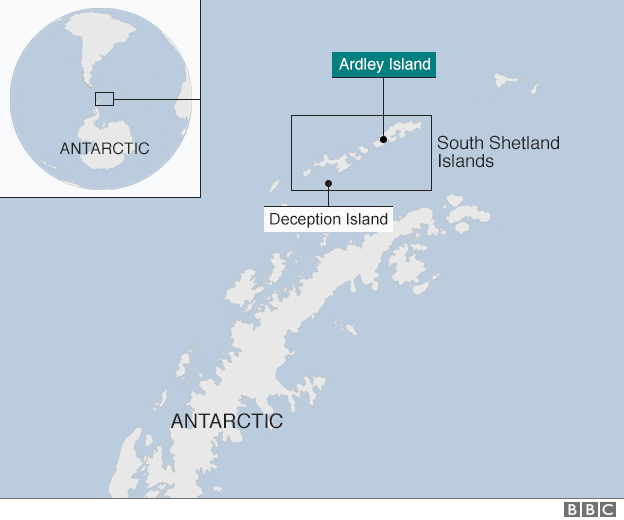

"What causes the biggest declines in the penguins is the volcanic activity on nearby Deception Island," explained Stephen Roberts from the British Antarctic Survey (BAS).

"Eruptions have gone off at regular intervals over the last 7,000 years. We found there were five phases when the penguin population grew quite significantly, and for three of these the population crashed. This was due to the volcano going off," he told BBC News.

Dr Stephen Roberts: "These cores were really quite smelly"

Dr Roberts' international team was drilling into the bottom of the lake, and four others across the Antarctic Peninsula's South Shetland Islands, to try to find evidence of past changes in sea-level.

Lakes that have spent any time under ocean water will have been invaded by marine organisms and it is their remains that will dominate the sediments. Instead, the team was confronted by the stench of ancient guano.

"When we brought the cores back to the lab, they were really quite smelly. We deal with rotten organic matter within cores quite a lot but this was particularly smelly," recalled Dr Roberts.

Bony fragments were found within the 3.5m of sediment cores recovered from Ardley

Like a penguin "Pompeii", the Ardley lake sediments contain the bony traces of animals caught in the ash fall.

The team recovered talons and vertebrae from juveniles that were presumably unable to get away and were smothered.

This is, though, a story of resilience - of the penguins finding a way to bounce back. It may have taken a few centuries on occasions, but eventually they do rebuild their numbers.

A gentoo penguin will produce, on average, about 85g of guano a day

And that is characteristic in general of Ardley's birds which are, in the main, gentoos.

Unlike their Pygoscelis, or "brush-tailed", cousins, the adélie and chinstrap penguins - the gentoos are in the ascendant. As the Antarctic Peninsula warms - and it is one of the fastest warming locations on Earth right now - the gentoos are flourishing.

"They are less ice-adapted than the adélies and the chinstraps. This is what we think, although we're not absolutely sure," commented Dr Claire Waluda, a marine ecologist from BAS who specialises in penguins.

"Gentoos eat more fish, whereas adélies and chinstraps like krill (shrimp) and the krill breed under the ice shelves, so if you have more ice you have more krill and more krill-dependent penguins."

Dr Claire Waluda: "Ardley is one of the biggest gentoo colonies"

Gentoos seem somewhat more flexible, both in diet and habitat. They tend not to nest in huge colonies and are not so attached to particular sites, taking up new areas if necessary.

They also seem to quite enjoy the warmer conditions of the peninsula's northern extent. "On very hot days you can see adélies panting; that's not something gentoos seem to do," said Dr Waluda.

The dating of moss fragments in the Ardley sediments reveals penguins get established on the island about 6,700 years ago, once the area becomes deglaciated. This pre-dates the skeletal evidence for peninsula-wide occupation by about 1,000 years.

The birds then experience five peaks in population (today's gentoos number about 5,000 breeding pairs), with eruptions resulting in their local near-extinction around 5,500 years ago, 4,300 years ago, and again some 3,000 years ago.

Deception Island is situated roughly 120km to the southwest of Ardley and its big neighbour, King George Island.

The eruptions on Deception in the deep past were much more powerful than today

The Deception volcano has blown its top 20-30 times in the last 200 years, but the ash-fall data from Ardley confirms the events further back in time must have been far more explosive.

Modern eruptions, such as those during 1967–1970, are a greater risk to the penguins on Deception itself.

There, the birds can get caught in pyroclastic flows, in which great clouds of ash and hot rock cascade downhill, burying everything in their path - similar to what happened to the people of the real Pompeii in AD 79.

The Ardley study is published in the journal Nature Communications, external.

The lake that was drilled by the team can be seen at centre-top

Jonathan.Amos-INTERNET@bbc.co.uk, external and follow me on Twitter: @BBCAmos, external