Primitive human 'lived much more recently'

- Published

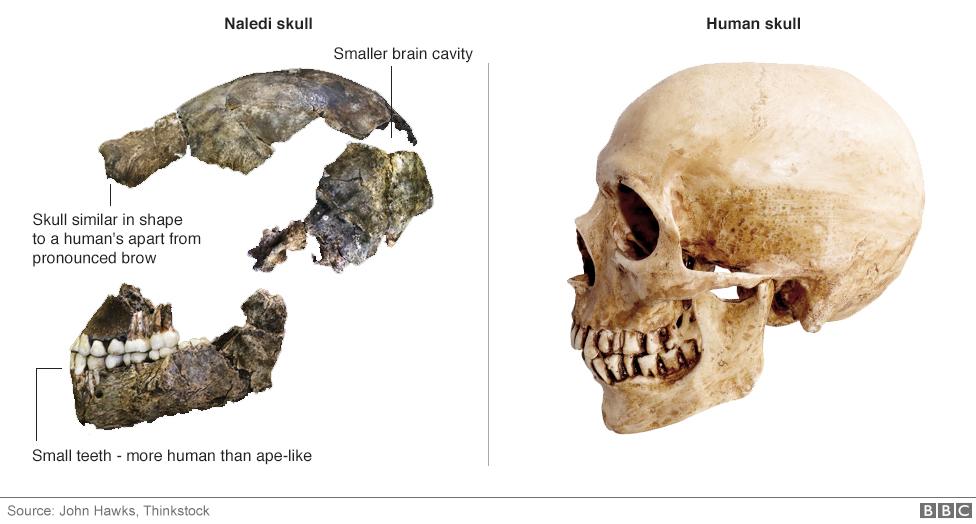

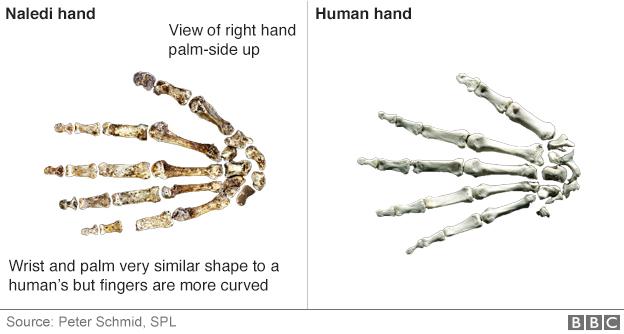

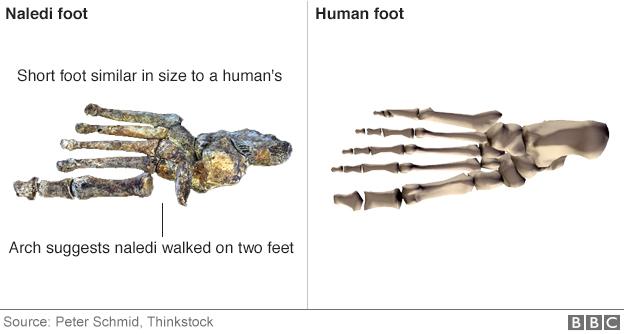

Homo naledi has much in common with early forms of the genus Homo

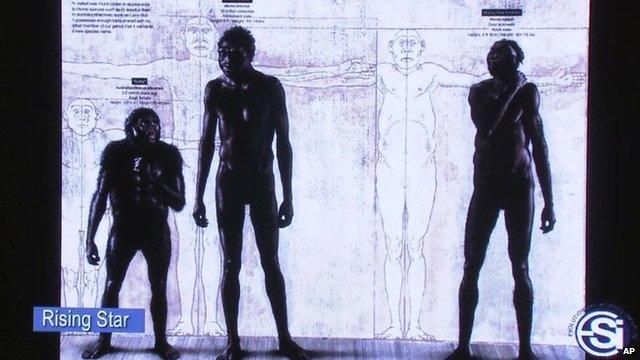

A primitive type of human, once thought to be up to three million years old, actually lived much more recently, a study suggests.

The remains of 15 partial skeletons belonging to the species Homo naledi were described in 2015.

They were found deep in a cave system in South Africa by a team led by Lee Berger from Wits University.

In an interview, he now says the remains are probably just 200,000 to 300,000 years old, external.

Although its anatomy shares some similarities with modern people, other anatomical features of Homo naledi hark back to humans that lived in much earlier times - some two million years ago or more.

"These look like a primitive form of our own genus - Homo. It looks like it might be connected to early Homo erectus, or Homo habilis, Homo rudolfensis," said Prof Berger's colleague, John Hawks, from the University of Wisconsin.

Although some experts guessed that naledi could had lived relatively recently, in 2015, Prof Berger told BBC News that the remains could be up to three million years old.

New dating evidence places the species in a time period where Homo naledi could have overlapped with early examples of our own kind, Homo sapiens.

Prof Hawks told the BBC's Inside Science radio programme: "They're the age of Neanderthals in Europe, they're the age of Denisovans in Asia, they're the age of early modern humans in Africa. They're part of this diversity in the world that's there as our species was originating."

"We have no idea what else is out there in Africa for us to find - for me that's the big message. If this lineage, which looks like it originated two million years ago was still hanging around 200,000 years ago, then maybe that's not the end of it. We haven't found the last [Homo naledi], we've found one."

The naledi remains were uncovered in 2013 inside a difficult-to-access chamber within the Rising Star cave system. At the time, Prof Berger said he believed the remains had been deposited in the chamber deliberately, perhaps over generations.

This idea, which would suggest that Homo naledi was capable of ritual behaviour, met with controversy because such practices are thought by some to be characteristic of human modernity.

Prof Hawks says that the team has since started exploring a second chamber.

"[The second] chamber has the remains of an additional three individuals, at least, including a really, really cool partial skeleton with a skull," said Prof Hawks.

Researchers have already attempted to extract DNA from the remains to gain more information about naledi's place in the human evolutionary tree. However, they have not yet been successful.

"[The remains] are obviously at an age where we have every reason to think there might be some chance. The cave is relatively warm compared to the cold caves in northern Europe and Asia where we have really good DNA preservation," said Prof Hawks.

A study outlining the dating evidence is due for publication in coming months.

Follow Paul on Twitter., external

For more on the Homo naledi remains, Inside Science is broadcast on Thursday 27 April at 16:30 BST on BBC Radio 4.

- Published10 September 2015

- Published6 October 2015

- Published25 September 2015