Albatrosses counted from space

- Published

Peter Fretwell: "We're working on algorithms that will automatically count the birds"

Scientists have started counting individual birds from space.

They are using the highest-resolution satellite images, external available to gauge the numbers of Northern Royal albatrosses, external.

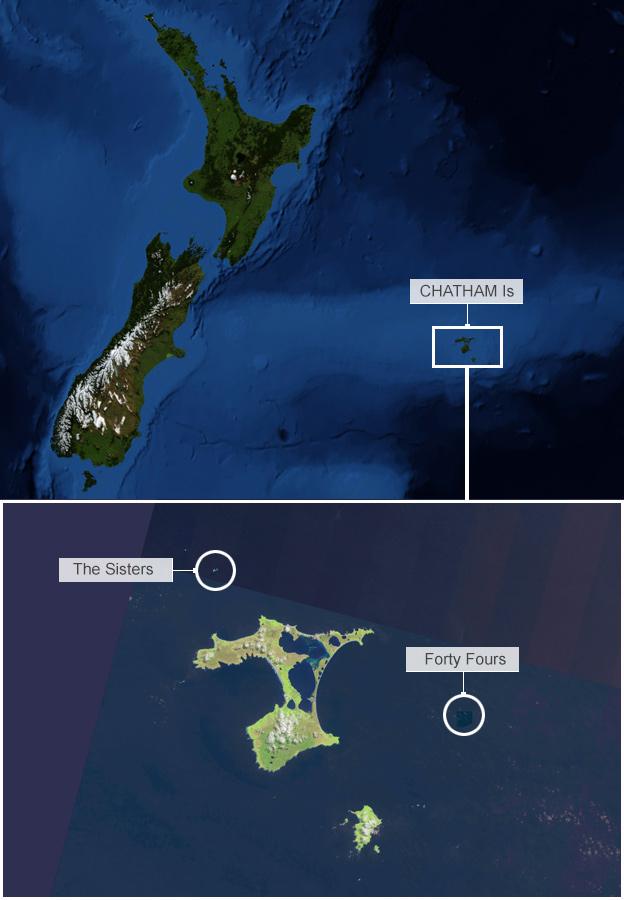

This endangered animal nests almost exclusively on some rocky sea-stacks close to New Zealand’s Chatham Islands.

The audit, led by experts at the British Antarctic Survey, external, represents the first time any species on Earth has had its entire global population assessed from orbit.

The scientists report the satellite technique in Ibis, external, a journal of the British Ornithologists' Union.

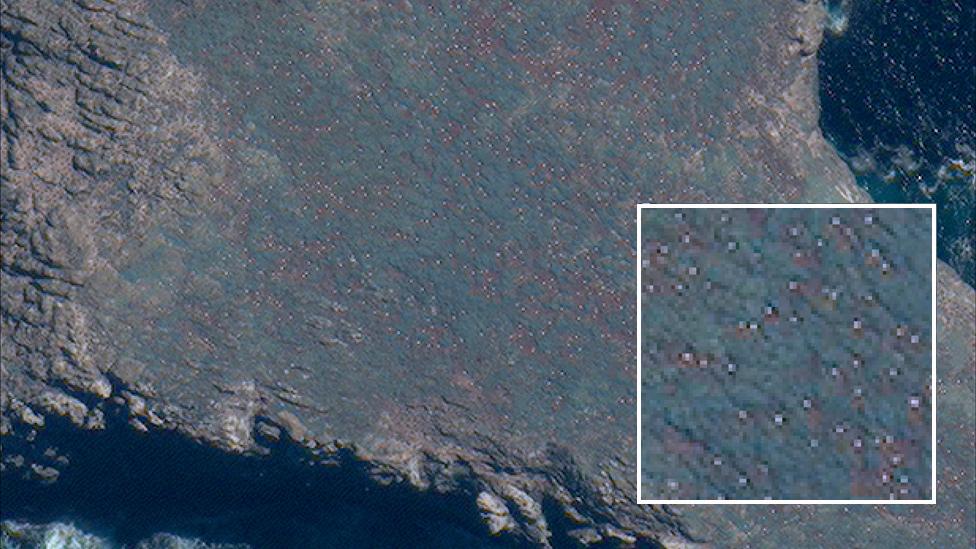

Craggy outcrop: At first glance there may not be much to look at...

It is likely to have a major impact on efforts to conserve the Northern Royals (Diomedea sanfordi).

Ordinarily, these birds are very difficult to appraise because their nesting sites are so inaccessible.

Not only are the sea-stacks far from NZ (680km), but their vertical cliffs mean that any visiting scientist might also have to be adept at rock climbing.

"Getting the people, ships or planes to these islands to count the birds is expensive, but it can be very dangerous as well," explained Dr Peter Fretwell from BAS.

This makes the DigitalGlobe WorldView-3 satellite something of a breakthrough.

It can acquire pictures of Earth that capture features as small as 30cm across.

...but the more you examine the WorldView-3 images, you begin to notice white dots

The US government has only recently permitted such keen resolution to be distributed outside the military and intelligence sectors.

WorldView-3 can see the nesting birds as they sit on eggs to incubate them or as they guard newly hatched chicks.

With a body length of over a metre, the adult albatrosses only show up as two or three pixels, but their white plumage makes them stand out against the surrounding vegetation. The BAS team literally counts the dots.

WorldView-3 provides a lot of imagery to the US government

The researchers first checked their methodology at Bird Island, South Georgia.

This is a unique nature reserve in the South Atlantic where the nests of another species of great albatross, the Wandering albatross (Diomedea exulans), are individually marked with GPS locators.

The biggest confounding factor is large, light-coloured rocks. But the analysis showed the team could get a very close match between the pixelated birds in the space images and the nests that were recorded in the ground-truth data.

There tends to be a slight over-counting, which the team puts down to breeding partners or non-breeding birds also being captured in a satellite scene.

Applying the technique at the Chatham Islands, the team counted just over 3,600 nests. This is slightly down on a manual count of 5,700 that was made in 2009.

Dr Fretwell said: "The breeding numbers we counted were much lower than we anticipated, which could show us that the population is declining or it could show just that we had a particularly poor year. But this illustrates why you have to do this over several years, and doing it by satellite is going be a lot cheaper and more efficient."

The birds favour sea-stacks known as The Sisters and the Forty Fours

Dr Paul Scofield at Canterbury Museum, NZ, is a co-author on the Ibis paper.

He described the difficulty of counting the birds in the traditional way at the group of stacks known as the Forty Fours.

"The 44s are particularly tricky," he told BBC News. "I once waited a whole month on the main Chatham Island for the weather to clear so I could land.

"Even if you use a plane, it's a problem as planes are only available infrequently and the wind and cloud prevent flying. Then if you take photos, you have to count them. That can take 100s of hours. This technology still requires the satellite to be in the right place and no cloud but it is certainly cheaper and more reliable."

A Buller's albatross looks across the tall cliffs of the Forty Fours

Like the other five species of great albatross, Northern Royals are under pressure for a variety of reasons.

Commercial fishing has depleted the stocks on which these seabirds also feed, and the baited longline gear used by some vessels has an unpleasant knack for attracting foragers and pulling them underwater where they drown.

But the Northern Royals in particular are vulnerable because of their desire to nest only on the Chatham Islands sea-stacks. If one big storm rolls through at the wrong time of year, it can severely dent breeding success.

"In 1986, a huge storm washed waves over these 50m-tall islands," said Dr Scofield.

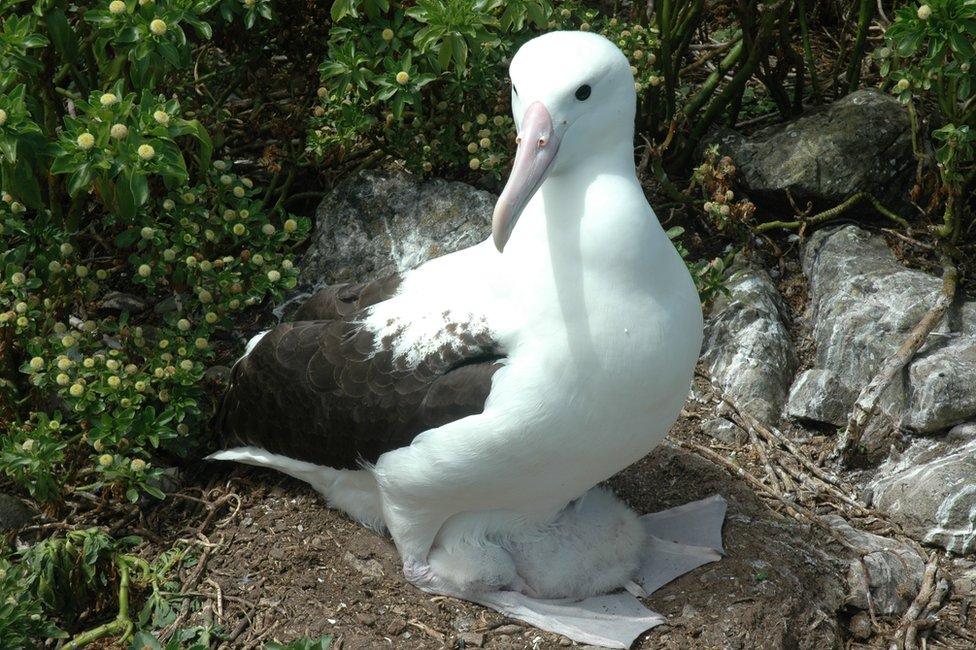

Creature of habit: Northern Royal albatrosses nest almost exclusively around the Chatham Islands

Jonathan.Amos-INTERNET@bbc.co.uk, external and follow me on Twitter: @BBCAmos, external

- Published13 August 2014

- Published12 February 2014

- Published13 April 2012