Amazing haul of ancient human finds unveiled

- Published

The male H. naledi specimen named "Neo", after being freed from the surrounding matrix

A new haul of ancient human remains has been described from an important cave site in South Africa.

The finds, including a well-preserved skull, bolster the idea that the Homo naledi people deliberately deposited their dead in the cave.

Evidence of such complex behaviour is surprising for a human species with a brain that's a third the size of ours.

Despite showing some primitive traits it lived relatively recently, perhaps as little as 235,000 years ago.

That would mean the naledi people could have overlapped with the earliest of our kind - Homo sapiens.

In a slew of papers published in the journal eLife, external, Prof Lee Berger from the University of the Witwatersrand in Johannesburg, Prof John Hawks from the University of Wisconsin-Madison, US, and their collaborators have outlined details of the new specimens and, importantly, ages for the remains.

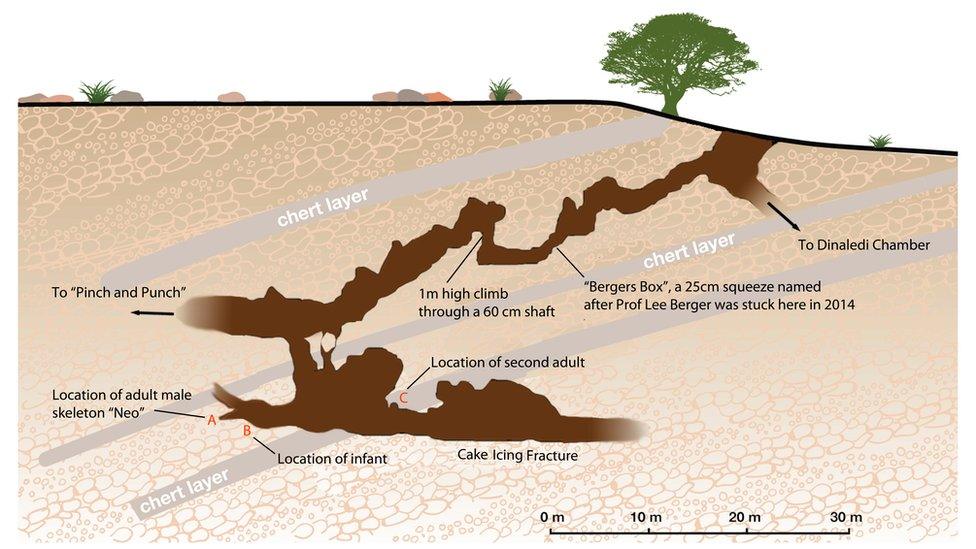

The H. naledi story starts in 2013, when the remains of almost 15 individuals of various ages were discovered inside the Dinaledi chamber - part of South Africa's Rising Star Cave system.

At the same time, the researchers were exploring a second chamber about 100m away, known as Lesedi ("light" in the Setswana language which is spoken in the region).

The Lesedi chamber yielded the remains of two adults and a child

The finds from Dinaledi were published in 2015, but remains from the Lesedi chamber had not previously been presented, until now.

The latest specimens include the remains of at least three individuals - two adults and a child.

One of the adults has a "wonderfully complete skull", according to Prof Hawks. This tough-looking specimen is probably male, and has been named "Neo", which means "a gift" in the Sesotho language of southern Africa.

Examination of its limb bones shows that it was equally comfortable climbing and walking.

The fact that Homo naledi was alive at the same time and in the same region of Africa as early representatives of Homo sapiens gives us an insight into the huge diversity of different human forms in existence during the Pleistocene.

"Here in southern Africa, in this time range, you have the Florisbad skull, which may be an ancestor or close relative of modern humans; you've got the Kabwe skull, which is some kind of archaic human and possibly quite divergent; you've got evidence from modern people's genomes that archaic lineages have been contributing to modern populations and may have existed until quite recently," said Prof Hawks.

H. naledi (R) seems to have shared southern Africa with distinct human species, such as Kabwe man (L)

"You have this very primitive form of Homo [naledi] that has survived alongside these other species for a million years or more. It is amazing the diversity that we are now seeing that we had missed before."

As to how H. naledi held on to its distinctive characteristics while living cheek-by-jowl with other human species, Prof Hawks said: "It's hard to say it was geographic isolation because there's no boundary - no barrier. It's the same landscape from here to Tanzania; we're in one continuous savannah, woodland-type habitat.

He added that the human-sized teeth probably reflected a diet like that of modern humans. In addition, H. naledi had limb proportions just like ours and there is no apparent reason why it could not have used stone tools.

"It doesn't look like they're in a different ecological niche. That's weird; it's a problem. This is not a situation where we can point to them and say: 'They co-existed because they're using resources differently'," Prof Hawks told BBC News.

Neo (R) is even more complete than the famous Lucy skeleton from Ethiopia (L)

The researchers say that finding the remains of multiple individuals in a separate chamber bolsters the idea that Homo naledi was caching its dead. If correct, this surprising - and controversial claim - hints at an intelligent mind and, perhaps, the stirrings of culture.

By dating the site, researchers have sought to clear up some of the puzzles surrounding the remains.

In 2015, Prof Berger told BBC News that the remains could be up to three million years old based on their primitive characteristics. Yet the bones are only lightly mineralised, which raised the possibility that they might not be very ancient (although this is not always an accurate guide).

In order to arrive at an age, the team dated the bones themselves, sediments on the cave floor and flowstones - carbonate minerals formed when water runs down the wall or along the floor of a cave.

Several techniques were used: optically stimulated luminescence to date the cave sediments, uranium-thorium dating and palaeomagnetic analyses for the flowstones and combined U-series and electron spin resonance (US-ESR) for dating three naledi teeth.

By combining results together, they were able to constrain the age of the Homo naledi remains to between 236,000 and 335,000 years ago.

Team members stand near one of the entrances to the Rising Star cave system

"We've got a geological bracket based on flowstones overlying the fossils and we've had direct dates on the teeth themselves," said John Hawks.

The team sent samples to two separate labs to perform their analyses "blind". This meant that neither lab knew what the other was doing, or what their analytical approaches were. Despite this, they returned the same results.

"This is now the best dated site in southern Africa - we threw everything at it," said John Hawks.

Commenting on the dates, Prof Chris Stringer, of London's Natural History Museum, said: "This is astonishingly young for a species that still displays primitive characteristics found in fossils about two million years old."

Apart from one well known exception (the Indonesian "Hobbit"), Prof Stringer explained, "the discovery and dating also question the usual assumption that... selection universally drove the evolution of a larger brain in humans during the last million years."

Many mysteries remain about this intriguing member of the human family tree. Not least of them is H. naledi's evolutionary history up until the point the remains show up in the Rising Star cave system.

Researchers currently envisage two possibilities. The first is that H. naledi represents one of these earliest branches of Homo - perhaps something like Homo habilis. It retains a rather primitive anatomy while evolving in parallel with the branch of the human family tree that eventually results in modern humans.

The other possibility is that it diverged more than a million years ago from a more advanced form of Homo - perhaps Homo erectus - and then reverted to a more primitive form in some aspects of its skull and teeth.

Follow Paul on Twitter., external