Safeguarding Islam's past for future generations

- Published

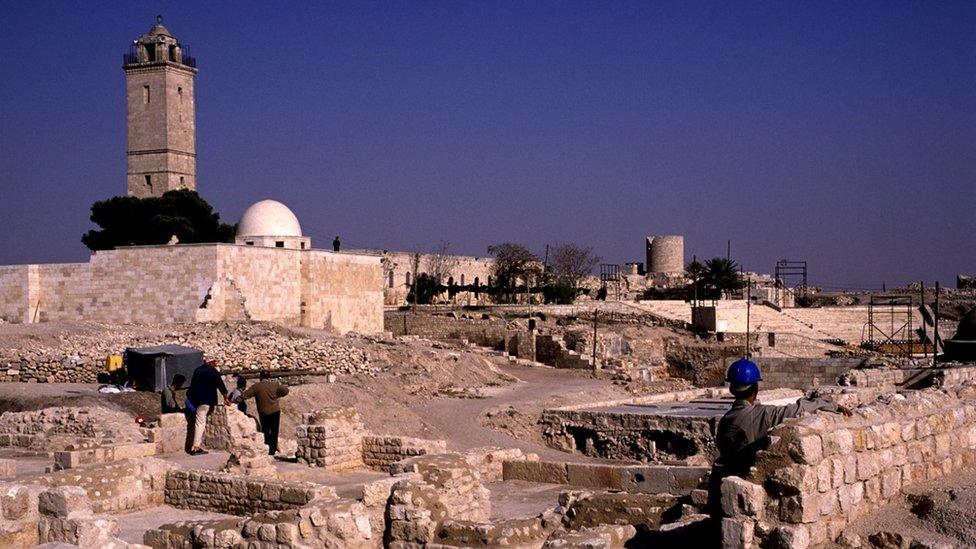

The citadel in Aleppo, Syria, has suffered damage during the country's six-year-long conflict

A recent conference in Bahrain brought together experts in Islamic archaeology to discuss the lessons of the past and how to safeguard Muslim heritage for future generations.

Under the blistering Bahraini sun archaeologist Salman Al Mahari and his team are excavating a section on the western side of the Al-Khamis mosque site.

With its twin minarets the mosque used to act as a landmark for ships at sea guiding them to land in the 14th century.

But today, excavating the mosque has a far more important function as Islamic archaeology takes on the extremists at their own game.

At a recent conference in Manama, the capital of Bahrain, archaeologists working in over 14 Islamic countries around the world participated in a first of its kind conference.

Islamic Archaeology in Global Perspective brought together some of the most distinguished scholars working in the field of Islamic archaeology to share first hand their recent practical experience in countries torn apart by war, and to investigate the various influences on the science of archaeology.

New Zealander, Alan Walmsley, Professor of Islamic Archaeology and Art at the University of Copenhagen says his investigations aim to disseminate a fuller account of social, cultural, and economic developments in Arab and Islamic history. "I interrogate faded and misinformed historical narratives," he explains.

He begins by unpicking past Western interest in Bilad Al-Sham, an historic region of the Middle East known as Greater Syria.

"Islamic discoveries were incidental to the objective of archaeological interest in Greater Syria," he says."The focus of digs were on the Biblical, Hellenistic and Classical past. These earlier periods took precedence in research."

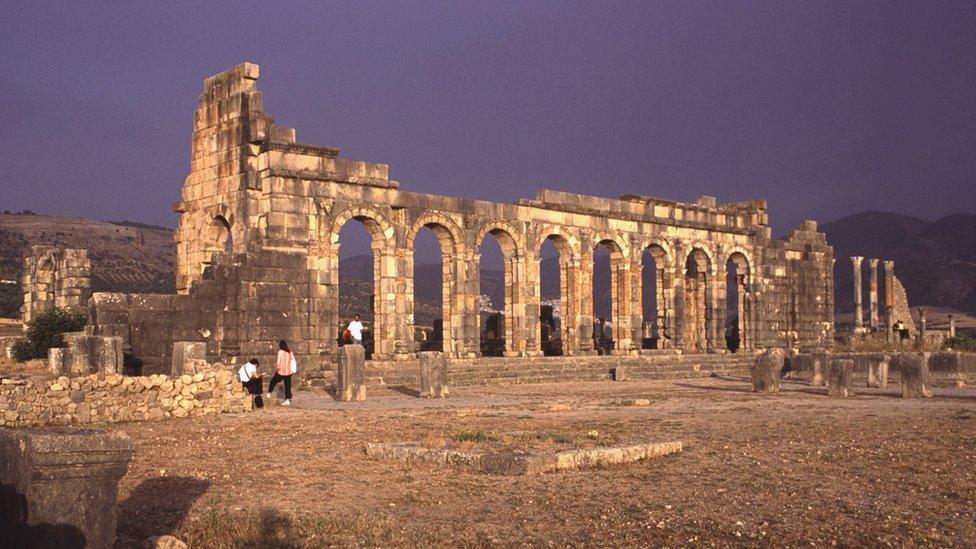

The site of Volubilis in Morocco is a Roman and Islamic site

Animosity between Islam and the West compounded the lack of interest in Muslim remains according to Alastair Northedge, professor at the Universites de Paris 1.

He spoke in the context of his recent trip to Iraq, about the West's overwhelming concerns with their own past. "There is quite a good example in Iraq," he says. "Babylon seems to belong to the West."

Corisande Fenwick, a lecturer in Archaeology of the Mediterranean at University College London (UCL) took time to describe painstaking research into food remains indicating when pork was no longer consumed and so revealing the pace at which Islam was established across the Maghreb region.

She attributes the Western assessment of archaeological finds prior to the mid-1950s to a colonial interpretation.

"If you go back before independence, archaeology is all driven by colonial scholars," she says.

"They were attracted by the exotic nature of their finds. That reinforced the idea that the Islamic world was somehow different and needed to be controlled by colonial powers," she adds.

But it is not just a Western agenda that has shaped excavations in the Muslim world. Alastair Northedge also notes that Muslims themselves have not always been concerned with protecting the material heritage of the great spiritual sanctuaries.

"It is not just Mecca and Medina, but also Shia shrines in Najaf and Karbala in Iraq" he says.

"There seems to be a preference for building something new rather than conserving the old because the emphasis is on the spiritual nature of these places not their materiality."

But a wider vision is coming and the rise in the number of excavations throughout the Gulf area attests to a burgeoning interest in the material past. St John Simpson, archaeologist and senior curator at the British Museum, says that a revival of interest in Islamic archaeology is long overdue.

"It's part and parcel of a search for Muslim cultural identity," he explains. It is also an opportunity to redress earlier misconceptions.

"Since the 19th century and continuing though much of the 20th century commercial excavations led by dealers have in parts of the world flooded the market with objects which were traditionally celebrated by art historians," Dr Simpson says. "They celebrated the beauty of those pieces and therefore reconstructed material cultures on the basis of those objects."

The Umayyad Mosque in Aleppo is more than 1,000 years old. Its famous minaret was destroyed in 2013

This world of appreciation driven by beauty is the natural perspective of art historians who rate aesthetics over function. "So metal ware, certain types of glass and glazed ceramics are elevated slightly disproportionately to their real functional value in the past.

"Metal ware, glass and glazed ceramics are more highly rated than pottery, brass or plain glass and unfortunately that gives a rather skewed impression," he says.

This new phase is also putting the spotlight on less well known aspects of the Muslim world. Saudi Arabian archaeologist Saad bin Abdulaziz Al Rashid says the Saudi Authority for Tourism and Heritage is in the process of broadening its scope beyond the Holy Places.

"Dams, wells, springs, fortresses along pilgrim tourist routes are all key to the understanding of the spread of Islam," he says.

"We are maintaining the Islamic cultural identity while ensuring their future sustainability," he asserts.

"These sites are significant not only to Muslims at large, but also to non-Muslim scholars and as part of the archaeological work we are supporting the transference and dissemination of the facts surrounding Islamic history."

Saad in Abdulaziz Al Rashid goes on to cite the rich remains of the Nabataean cities of Al Ula and Mada'n Saleh, the furthest western outpost of the civilisation centred at Petra in Jordan. "These first century tombs are now a tourist attraction." he states.

Meanwhile Alastair Northedge notes that the contemporary, more comprehensive vision of Islam counterbalances the extremist fixation with the time of the Prophet.

"All that millennium and a half of great Islamic civilisation, the golden age, has tended to disappear," he comments. "That means forgetting discoveries in philosophy, science that can tell us so much."

Now educated mainstream Muslims are seeking an intelligent tolerant Islam they can relate to and which is absent from Islamic State (IS) discourse.

Today's archaeologist may cross modern political frontiers shattering paradigms created within borders. A globalised archaeology sees expert working collaboratively in diverse countries across the Muslim world.

St John Simpson says that the British Museum is already working with Iraqi archaeologists to build capacity for a whole new generation.

"For a post-Daesh world where we can dig across Iraq safely, training schemes in southern and northern Iraq are helping prepare archaeologists."

Some Iraqi trainees are currently working in Mosul at a time of conflict making assessments of the archaeology and the damage to cultural property with a view that when peace is restored there can be reconstruction.

Nor far away from the conference taking place in Bahrain's National Theatre, Salman al-Mahari is looking at some newly unearthed tombstones.

"These are the same type of stones found in Shiraz, in south-central, Iran," he confirms. "They reflect the cultural and economic exchange between these two places dating from the 11th centuries and perhaps even earlier."

As well as introducing the notion of globalism to modern Islamic archaeology, the conference holds out the prospect of an objective assessment of current and previous findings that will offer a more balanced and revisionist account of the social history of Islam.