Lean-burn physiology gives Sherpas peak-performance

- Published

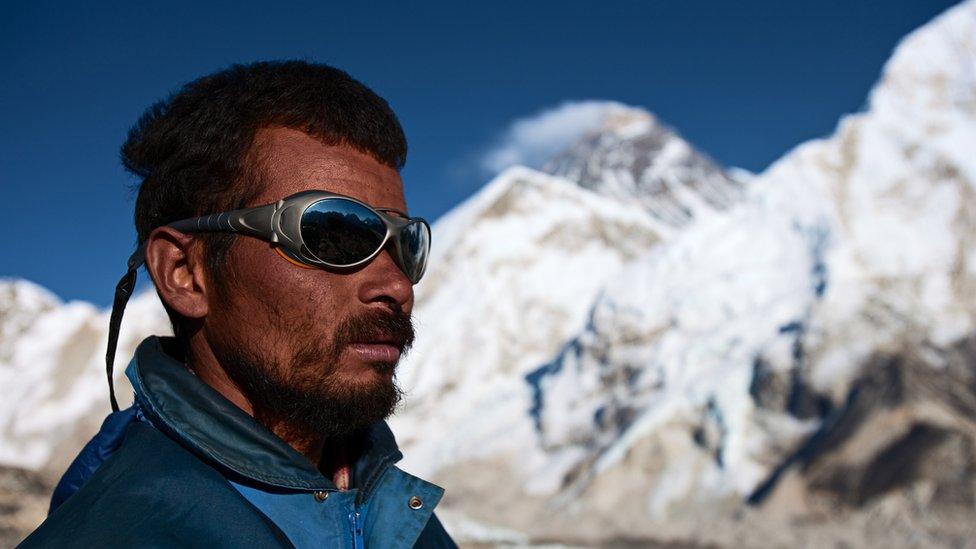

Science at the top of the world

Nepalese Sherpas have a physiology that uses oxygen more efficiently than those used to the atmosphere at sea level.

This is the finding of a new study that investigated high-altitude adaptation in mountain populations.

The research involved taking muscle samples from mountaineers at 5,300m altitude and even putting them on an exercise bike at Mt Everest Base Camp.

The Sherpas owe this ability to an advantageous genetic mutation that gives them a unique metabolism.

Sherpas have thinner blood than those who live at low altitudes

It has long been a puzzle that Sherpas can cope with the low-oxygen atmosphere present high in the Himalayas far better than those visiting the region.

Mountaineers trekking to the area can adapt to the low oxygen by increasing the number of red cells in their blood, increasing its oxygen-carrying capacity.

In contrast, Sherpas actually have thinner blood, with less haemoglobin and a reduced capacity for oxygen (although this does have the advantage that the blood flows more easily and puts less strain on the heart).

"This shows that it's not how much oxygen you've got, it's what you do with it that counts," concludes Cambridge University’s Prof Andrew Murray, the senior author on the new study.

"Sherpas are extraordinary performers, especially on the high Himalayan peaks. So, there's something really unusual about their physiology," he told the BBC World Service's Science In Action programme.

Three people who have scaled Mount Everest explain what it is like to stand on top of the world

Unravelling what is different involved a substantial scientific expedition to Everest Base Camp where the high-altitude response of 10 mostly European researchers and 15 elite Sherpas could be compared.

For participants like James Horscroft, whose PhD was based on the data he got from this Xtreme Everest 2 venture, external, this meant not just a chance to explore one of the planet’s most remote regions, but also a lot of pressure.

“It was very stressful, because we only had this one chance to get our data, high in the Himalaya."

For James, like all the others, those data included samples of muscle punctured from the thigh. While some samples were frozen to be taken back to university labs, others were experimented on in a makeshift lab at the base camp.

“We had to start at seven in the morning, because it took four hours to do all the tests on one sample," James said. "At that time, the temperature could be 10 degrees below freezing, so we'd be all wrapped up and wearing gloves. By late morning it would rise to plus-25, and we'd be taking all our kit off!"

Taking muscle samples from mountaineers at 5,300m altitude

What the biochemical tests on the fresh muscle showed was that the Sherpas' tissue was able to make much better use of oxygen by limiting the amount of body fat burned and maximising the glucose consumption.

"Fat is a great fuel, but the problem is that it's more oxygen hungry than glucose," Prof Murray explained.

In other words, by preferentially burning body sugar rather than body fat, the Sherpas can get more calories per unit of oxygen breathed.

The result impresses Federico Formenti of King’s College, London, whose own trekking study a decade ago, monitoring oxygen consumption through breath sensors, suggested Sherpas can produce 30% more power than lowlanders.

"This paper provides a cellular mechanism for what we found at the whole body level; that Sherpas use less oxygen to do the same job," he says.

James Horscroft agrees the difference in performance is impressive. "It was pretty clear straight away that our tissue experiments were showing different metabolisms for the two groups. In fact, the difference was so astounding we were worried if the tests were working."

But back in Cambridge the results were borne out. And a genetic variation altering the way fats are burned was established, too. While all of the Sherpas carried the glucose-favouring variant of the metabolic gene, almost none of the lowland volunteers did.

Sherpas are a specific population amongst the Nepalese ("the Ferraris of the Himalayans", Formenti calls them) who migrated to the country 500 years ago from Tibet, which has been occupied by humans for at least 6,000 years. That is plenty of time for a beneficial gene to become embedded, Prof Murray argues.

"It's not down to one gene, of course. We see better blood flow through the capillaries; and they appear to have a richer capillary network as well so that the oxygen can be delivered better to the tissues. But this gene would also have given them some advantage."

Other recent studies have shown that some genes that help Tibetans survive at high altitude come from the recently discovered extinct human species known as the Denisovans, although there is no evidence yet that the metabolic gene is among them.

The Sherpa study is published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, external.

You can hear an interview with Prof Murray on this week's Science In Action programme, to be broadcast first on Thursday.