'First of our kind' found in Morocco

- Published

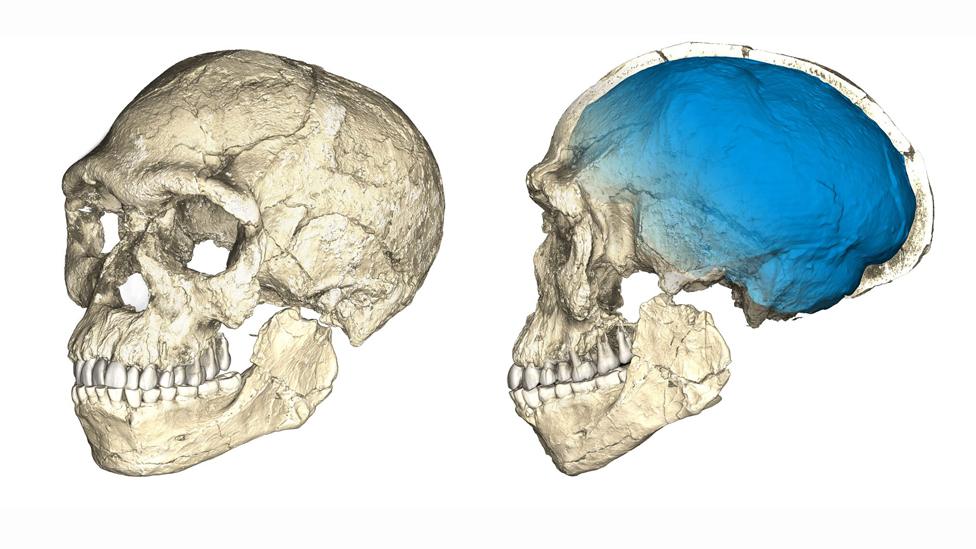

The shape of a Jebel Irhoud skull (L) is almost identical to ours (R)

The idea that modern people evolved in a single "cradle of humanity" in East Africa some 200,000 years ago is no longer tenable, new research suggests.

Fossils of five early humans have been found in North Africa that show Homo sapiens emerged at least 100,000 years earlier than previously recognised.

It suggests that our species evolved all across the continent, the scientists involved say.

Their work is published in the journal Nature, external.

Prof Jean-Jacques Hublin, of the Max Planck Institute (MPI) for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig, Germany, told me that the discovery would "rewrite the textbooks" about our emergence as a species.

"It is not the story of it happening in a rapid way in a 'Garden of Eden' somewhere in Africa. Our view is that it was a more gradual development and it involved the whole continent. So if there was a Garden of Eden, it was all of Africa."

A reconstruction of the earliest known Homo sapiens skull based on scans of multiple original fossils

Prof Hublin was speaking at a news conference at the College de France in Paris, where he proudly showed journalists casts of the fossil remains his team has excavated at a site in Jebel Irhoud in Morocco. The specimens include skulls, teeth, and long bones.

Earlier finds from the same site in the 1960s had been dated to be 40,000 years old and ascribed to an African form of Neanderthal, a close evolutionary cousin of Homo sapiens.

But Prof Hublin was always troubled by that initial interpretation, and when he joined the MPI he began reassessing Jebel Irhoud. And more than 10 years later he is now presenting new evidence that tells a very different story.

The latest material has been dated by hi-tech methods to be between 300,000 and 350,000 years old. And the skull form is almost identical to modern humans.

The few significant differences are seen in a slightly more prominent brow line and smaller brain cavity.

Prof Hublin's excavation has further revealed that these ancient people had employed stone tools and had learned how to make and control fire. So, not only did they look like Homo sapiens, they acted like them as well.

The Jebel Irhoud site in Morocco was recognised for its fossils from the 1960s

Until now, the earliest fossils of our kind were from Ethiopia (from a site known as Omo Kibish) in eastern Africa and were dated to be approximately 195,000 years old.

"We now have to modify the vision of how the first modern humans emerged," Prof Hublin told me with an impish grin.

Before our species evolved, there were many different types of primitive human species, each of which looked different and had its own strengths and weaknesses. And these various species of human, just like other animals, evolved and changed their appearance gradually, with just the occasional spurt. They did this over hundreds of thousands of years.

By contrast, the mainstream view has been that Homo sapiens evolved suddenly from more primitive humans in East Africa around 200,000 years ago; and it is at that point that we assumed, broadly speaking, the features we display now. What is more, only then do we spread throughout Africa and eventually to the rest of the planet. Prof Hublin's discoveries would appear to shatter this view.

A lower jaw from a Homo sapiens individual excavated at the Jebel Irhoud site

Jebel Irhoud is typical of many archaeological sites across Africa that date back 300,000 years. Many of these locations have similar tools and evidence for the use of fire. What they do not have is any fossil remains.

Because most experts have worked on the assumption that our species did not emerge until 200,000 years ago, it was natural to think therefore that these other sites were occupied by an older, different species of human. But the Jebel Irhoud finds now make it possible that it was actually Homo sapiens that left the tool and fire evidence in these places.

A selection of the stone tools recovered by Prof Hublin's team. The Jebel Irhoud individuals not only looked like us they did things typical of Homo sapiens

"We are not trying to say that the origin of our species was in Morocco - rather that the Jebel Irhoud discoveries show that we know that [these type of sites] were found all across Africa 300,000 years ago," said MPI team member Dr Shannon McPhearon.

Prof Chris Stringer from the Natural History Museum in London, UK, was not involved in the research. He told BBC News: "This shows that there are multiple places in Africa where Homo sapiens was emerging. We need to get away from this idea that there was a single 'cradle'."

And he raises the possibility that Homo sapiens may even have existed outside of Africa at the same time: "We have fossils from Israel that are probably the same age and they show what could be described as proto-Homo sapiens features."

Prof Stringer says it is not inconceivable that primitive humans who had smaller brains, bigger faces, stronger brow ridges and bigger teeth - but who were nonetheless Homo sapiens - may have existed even earlier in time, possibly as far back as half a million years ago. This is a startling shift in what those who study human origins believed not so long ago.

"I was saying 20 years ago that the only thing we should be calling Homo sapiens are humans that look like us. This was a view that Homo sapiens suddenly appeared in Africa at some point in time and that was the beginning of our species. But it now looks like I was wrong," Prof Stringer told BBC News.