'Boaty McBoatface' submarine returns home

- Published

Boaty undertook three dives with the longest conducted over three days

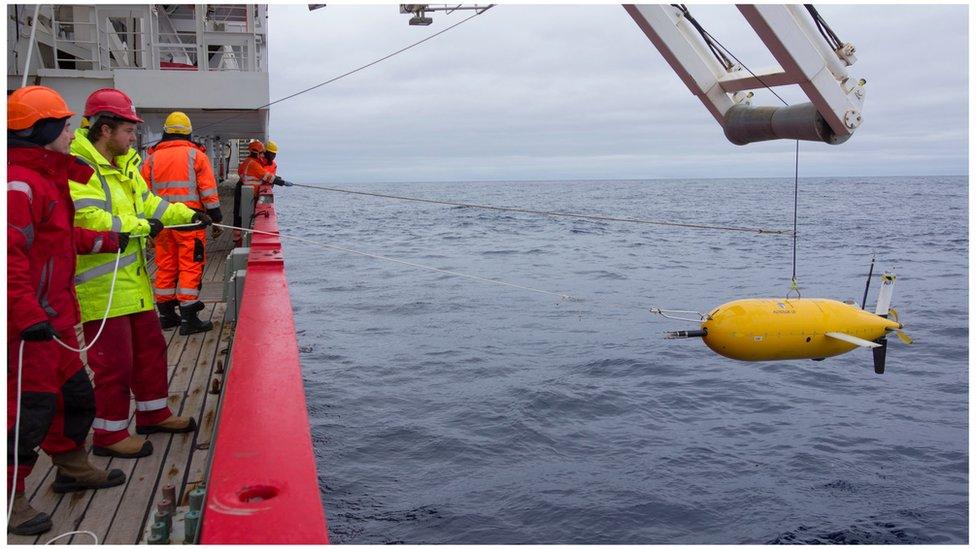

Boaty McBoatface, the UK's favourite yellow submarine, has returned from its first major science expedition.

The vehicle was used in the Antarctic to map the movement of deep, cold water as it moves away from the White Continent towards the Atlantic Ocean.

Scientists say this flow of water plays an important role in helping to regulate the Earth's climate system.

Boaty made a total of three dives, reaching down to 4,000m below the surface.

And by all accounts, it acquired a remarkable set of new data.

"We were extremely pleased with Boaty's performance," said Prof Alberto Naveira-Garabato from the University of Southampton, the lead scientist for the investigations conducted from the deck of the Royal Research Ship James Clark Ross, external.

"Boaty's longest dive was over three days, covering 180km. Boaty flew through some very strong currents, very close to the ocean bottom and encountered some really steep terrain. And it did this while running through a very complex sampling pattern."

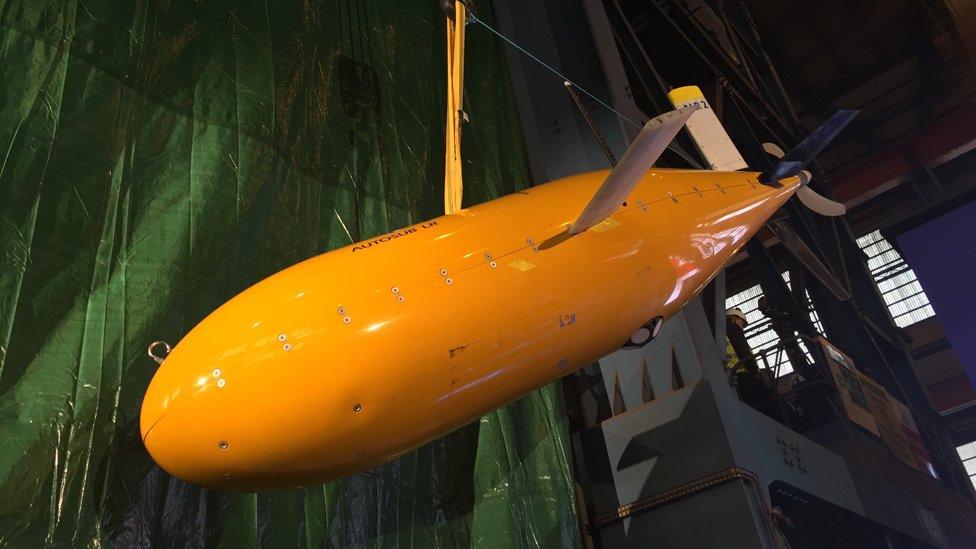

Boaty carries the name that a public poll had suggested be given to the UK's future £200m polar research vessel.

The government felt this would be inappropriate and directed the humorous moniker go on a submersible instead (the ship will be called the RSS Sir David Attenborough).

Southampton's National Oceanography Centre (NOC), external - the home of Boaty - is actually going to use the brand on three robots in its new Autosub Long Range class, external.

These subs have proven their capabilities in various sea trials but the Antarctic venture was the first full science expedition, proper.

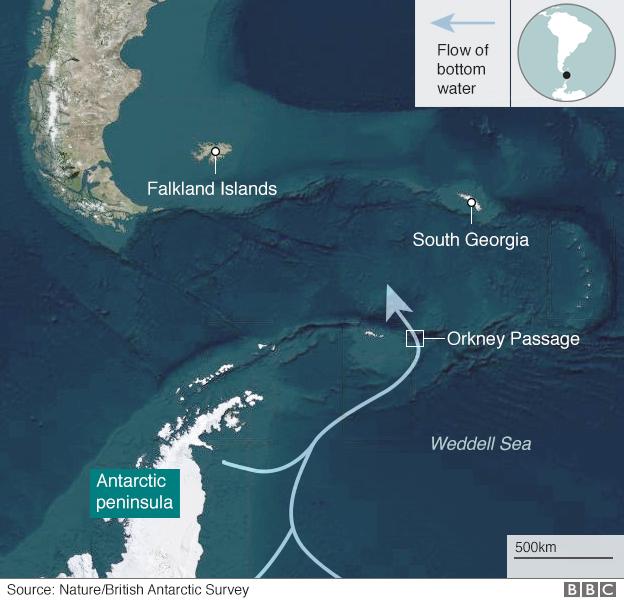

Bottom-water is generated at the margin of the continent and then spills north into the Atlantic

Boaty was programmed to swim through a narrow gap in the ocean-floor ridge that extends northeast of the Antarctic Peninsula.

Known as the Orkney Passage, this opening is a critical "valve" in the so-called "great ocean conveyor" - the relentless system of deep circulation that helps redistribute all the heat energy that has built up in the climate system.

There is evidence that this flow of bottom-water is warming, perhaps because of a strengthening of the winds over the Southern Ocean.

Prof Naveira-Garabato told BBC News: "When the winds change speed they can lead to an acceleration or deceleration of the currents carrying the bottom-water out of Antarctica. And when these currents change speed they will produce more or less turbulence depending on whether they go faster or slower, and that can change how much heat gets mixed into the currents from above, because the waters above are warmer."

That could have a number of important implications, not least for sea-level rise, because if the bottom-water is warming it will expand and push up the ocean surface.

Scientist Eleanor Frajka-Williams describes a Boaty dive through Orkney Passage

Boaty took temperature, salinity (saltiness), current, and turbulence measurements on its deep dives.

"On the cruise, we also took lots of measurements from the ship using profiling instruments, giving us very high-resolution in depth, but at a fixed point in time and space,” explained Dr Povl Abrahamsen from the British Antarctic Survey.

“And we recovered instruments that had been moored in the area over the last two years, giving us good coverage in time, but again at a fixed point and depth. The data from Boaty fills in the gaps between these measurements, yielding data that we can’t get in any other way."

The sub's exploits were not all trouble free, however. At the start of one dive, Boaty encountered a swarm of krill so dense that its echo sounders thought it was approaching the seabed even though it was only at 80m depth. The sub returned to the surface as a consequence.

"Boaty is cutting-edge technology, and is still under development. As is always the case when pushing the boundaries, a few minor mishaps did occur," said Dr Abrahamsen.

"But we learn from these problems, rectify them, and it makes Boaty more reliable in the future, enabling it to undertake more complex missions, farther away from ship support."

Jonathan.Amos-INTERNET@bbc.co.uk, external and follow me on Twitter: @BBCAmos, external

- Published11 April 2017

- Published13 March 2017

- Published17 October 2016

- Published17 October 2016