Inmarsat's European short-haul wi-fi spacecraft launches

- Published

The EAN will use a satellite that was launched from French Guiana on Wednesday by an Ariane rocket

A new Europe-wide wi-fi service for aeroplanes came a step closer on Wednesday night with the launch of a key satellite from French Guiana.

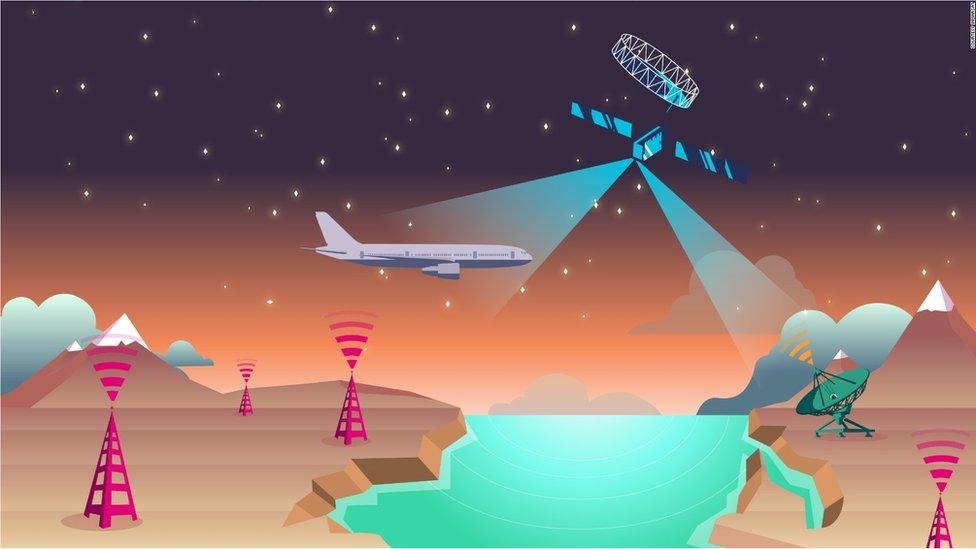

Airline passengers will soon be able to connect to the internet either through this spacecraft or a complementary system of cell towers on the ground.

The company behind the so-called European Aviation Network, external is Inmarsat, the UK's biggest satellite operator.

It is building the system in tandem with Deutsche Telekom of Germany.

The pair hope to start services at the back end of the year, with IAG Group (Aer Lingus, British Airways, Iberia and Vueling) being the first to install their planes with the necessary equipment. Lufthansa will be doing some testing also.

Antennas will be fixed on the top of aircraft to connect upwards to space, and other terminals will be put in the belly of planes to link down to what initially will be 300 4G-LTE towers concentrated along Europe's main short-haul routes.

The hybrid system would be a first for the continent.

Passengers in cabins wanting to surf the web or watch a video would simply join a hotspot as they would if they were in a cafe or a hotel.

The EAN is designed to be a hybrid network - connecting passengers via space and ground links

The European Aviation Network (EAN) has been a while coming. The European Commission first awarded two licences for satellite communications operating in the S-band part of the radio spectrum back in 2009; and expected services to be up and running by December of last year.

But both Inmarsat and the other licence holder made slow progress in developing a business case that would make best use of the frequency allocation.

In the beginning, many commentators thought that case might involve mobile phones which could connect either to a satellite or a local cell network. However, this was before in-flight connectivity (IFC) became a boom market.

Wi-fi on planes has traditionally had a wretched reputation, but the technologies are changing and the user experience is fast improving.

"We conjured lots of business cases and then during that journey along came IFC and it's a perfect fit," said Rupert Pearce, the CEO of Inmarsat.

"The short-haul market is growing twice as fast as in North America in terms of planes and passenger journeys, and it's set to become the largest short-haul aviation market in the world. Only briefly because I think China will over take it. China are going to build 50 airports in the next five years, so it's very hard to compete with them; but absent that, the European opportunity is very exciting."

The spacecraft also carried a payload for TV relay company Hellas-Sat

Already, the aero market is one of Inmarsat's fastest growing sectors, and it has big Ka-band satellites, dubbed Global Xpress, feeding connections to long-haul flights. The EAN is targeted specifically at the single-aisled planes making quick hops around Europe.

Deutsche Telekom has still to switch on the ground segment and debug it, says Mr Pearce; and the new satellite, launched on an Ariane rocket from Kourou on Wednesday, will take three to four months to commission. IAG and Lufthansa, who the CEO describes as strategic partners, can then start a period of testing, he adds.

But there is some serious push back from the competition.

Other satellite operators are critical of the Inmarsat offering, believing it to be an infringement of the original terms of the S-band licence awarded by the EC.

Satellite operators are engaged in a fierce battle to win a big slice of the IFC market

ViaSat, a big US concern best known for providing connections on aircraft in North America, is lodging a complaint with the European Court of Justice. It is being supported in this action by its European partner, Eutelsat, and Panasonic Avionics, which sells IFC services.

The trio contend that the S-band licence was supposed to be predominantly a satellite service with a back-up ground segment. Inmarsat, they say, has produced the opposite.

"There is a strong deviation from the original purpose," argued Wladimir Bocquet, Eutelsat's director of spectrum management and policy.

"Just one example - from calculations we see that the total capacity of the satellite component is, for Europe, 100 Megabits per second (Mbps). Compare that to the publicly stated capacity of the terrestrial component: it is around 50 Gigabits per second (Gbps). That's a factor of 500 difference. How can that be considered complementary. It's a terrestrial network. That's important when the selection process was done on the basis of the satellite element," he told BBC News.

Double licences: Inmarsat needs two permissions from each individual member state of the European Union

In 2020/21, Viasat and Eutelsat intend to put above Europe the most powerful satellite ever built, which will have a total throughput of 1 Terabit per second. This, they say, will offer far superior connections to planes than the EAN, but fear airlines may be about to lock themselves into an inferior service that was developed under a false prospectus.

"You either respect the rules and develop the business under the framework that has been agreed, or you say the framework is not appropriate and in that case you develop a new framework and you open to competitors the opportunity to enter into this new business with a new framework," said Mr Bocquet.

But the complaints have prompted a stinging response from Inmarsat and Mr Pearce. Asked to comment, he responded: "It's all tosh, to use the technical term."

And he essentially accused Eutelsat in particular of sour grapes. "They actually held the opposite licence. They won it with [the SES satellite operator] at the same time as we did. They could do nothing with it and eventually abandoned it by selling it to [the Echostar satellite operator] for not much money.

"Now they have the temerity to come back and say it was all evil. To say that the EC didn't know what it was doing is disingenuous at best.

"They're just trying to slow us down. They know we've backed a cool piece of technology that's going to drive jobs and growth as well as fantastic services on planes."

In order to run the EAN, Inmarsat does however need the individual permissions of each member state of the European Union - to have both a national licence for the space segment and the terrestrial element.

Inmarsat claims to have all EU member state space permissions (including from Norway and Switzerland), and is awaiting just three licences for the operation of the ground tower network - from Germany, France and the UK.

The London-based company told the BBC that the German and French authorities looked set for approval in the next few weeks. Ironically, Inmarsat expects the UK telecoms regulator, Ofcom, to be the last to fall in place.

Jonathan.Amos-INTERNET@bbc.co.uk, external and follow me on Twitter: @BBCAmos, external

- Published2 June 2017

- Published16 May 2017

- Published21 September 2015

- Published5 June 2014