Scientists explain ancient Rome's long-lasting concrete

- Published

Scientists examined samples from this ancient Roman pier with very high-powered X-rays

Researchers have unlocked the chemistry of Roman concrete which has resisted the elements for thousands of years.

Ancient sea walls built by the Romans used a concrete made from lime and volcanic ash to bind with rocks.

Now scientists have discovered that elements within the volcanic material reacted with sea water to strengthen the construction.

They believe the discovery could lead to more environmentally friendly building materials.

Unlike the modern concrete mixture which erodes over time, the Roman substance has long puzzled researchers.

Rather than eroding, particularly in the presence of sea water, the material seems to gain strength from the exposure.

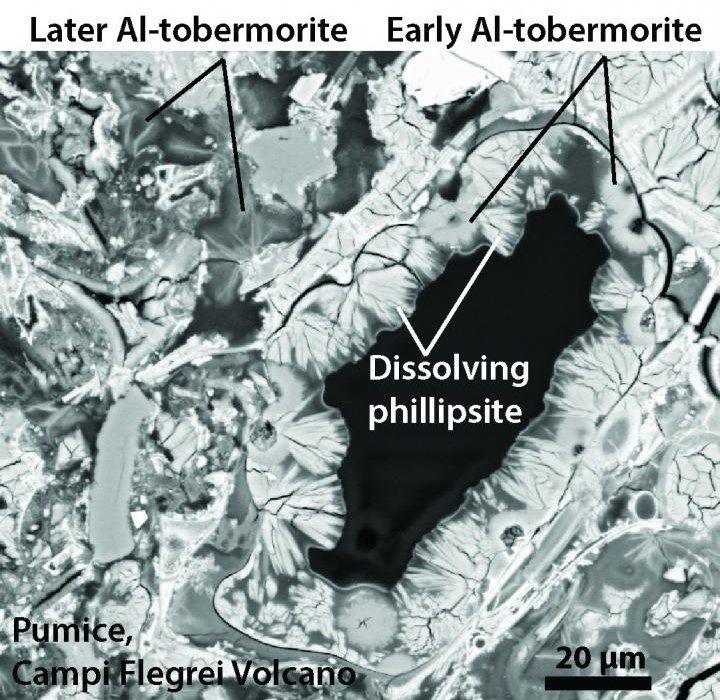

In previous tests with samples from ancient Roman sea walls and harbours, researchers learned that the concrete contained a rare mineral called aluminium tobermorite.

They believe that this strengthening substance crystallised in the lime as the Roman mixture generated heat when exposed to sea water.

Researchers have now carried out a more detailed examination of the harbour samples using an electron microscope to map the distribution of elements. They also used two other techniques, X-ray micro-diffraction and Raman spectroscopy, to gain a deeper understanding of the chemistry at play.

This new study says the scientists found significant amounts of tobermorite growing through the fabric of the concrete, with a related, porous mineral called phillipsite.

The researchers say that the long-term exposure to sea water helped these crystals to keep on growing over time, reinforcing the concrete and preventing cracks from developing.

"Contrary to the principles of modern cement-based concrete," said lead author Marie Jackson from the University of Utah, US, "the Romans created a rock-like concrete that thrives in open chemical exchange with seawater."

A close up view of the concrete from a scanning electron microscope showing the presence of the tobermorite which adds strength

"It's a very rare occurrence in the Earth."

The ancient mixture differs greatly from the current approach. Modern buildings are constructed with concrete based on Portland cement.

This involves heating and crushing a mixture of several ingredients including limestone, sandstone, ash, chalk, iron and clay. The fine material is then mixed with "aggregates", such as rocks or sand, to build concrete structures.

The process of making cement has a heavy environmental penalty, being responsible for around 5% of global emissions of CO2.

So could the greater understanding of the ancient Roman mixture lead to greener building materials?

Prof Jackson is testing new materials using sea water and volcanic rock from the western United States. Speaking to the BBC earlier this year, she argued that the planned Swansea tidal lagoon should be built using the ancient Roman knowledge of concrete.

"Their technique was based on building very massive structures that are really quite environmentally sustainable and very long-lasting," she said.

"I think Roman concrete or a type of it would be a very good choice [for Swansea]. That project is going to require 120 years of service life to amortise [pay back] the investment.

"We know that Portland cement concretes contain steel reinforcements. Those will surely corrode in at least half of that service lifetime."

There are a number of limiting factors that make the revival of the Roman approach very challenging. One is the lack of suitable volcanic rocks. The Romans, the scientists say, were fortunate that the right materials were on their doorstep.

Another drawback is the lack of the precise mixture that the Romans followed. It might take years of experimenting to discover the full formula.

The research has been published in the journal American Mineralogist, external.

Follow Matt on Twitter, external and on Facebook, external