The algae that terraformed Earth

- Published

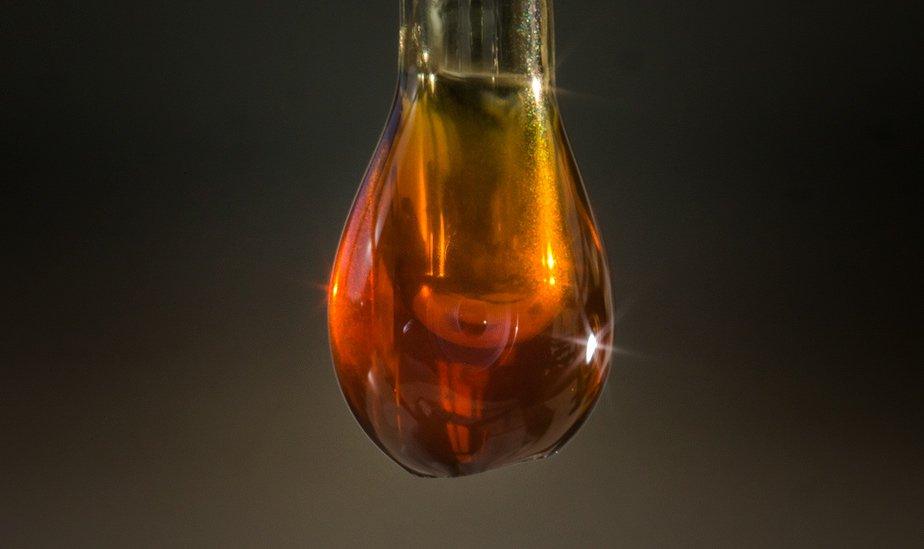

The biomolecules were contained in oil extracted from deeply buried rock

A planetary takeover by ocean-dwelling algae 650 million years ago was the kick that transformed life on Earth.

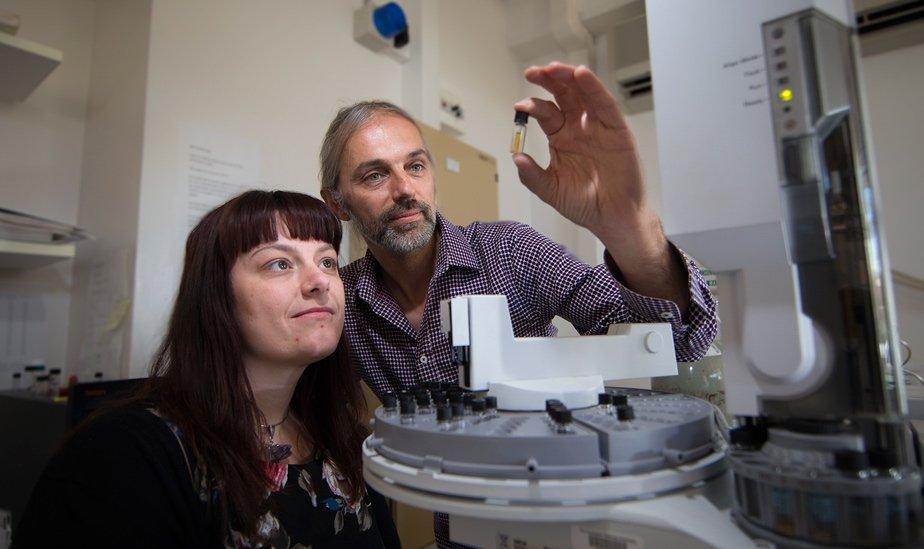

That's what geochemists argue in Nature this week, external, on the basis of invisibly small traces of biomolecules dug up from beneath the Australian desert.

The molecules mark an explosion in the quantity of algae in the oceans.

This in turn fuelled a change in the food web that allowed the first microscopic animals to evolve, the authors suggest.

"This is one the most profound ecological and evolutionary transitions in Earth's history," lead researcher Jochen Brocks told the BBC's Science in Action programme.

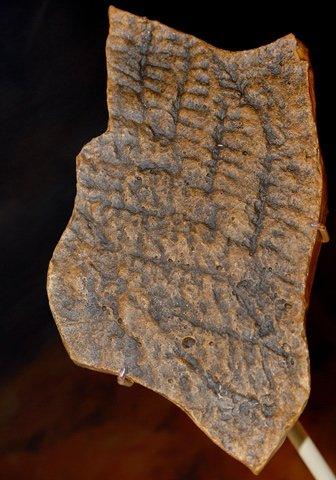

The events took place a hundred million years before the so-called Cambrian Explosion, an eruption of complex life recorded in fossils around the world that puzzled Darwin and always hinted at some kind of biological prehistory.

Scattered traces of those precursor multi-celled organisms have since been recognised, but the evolutionary driver that led to their rise has been much argued over.

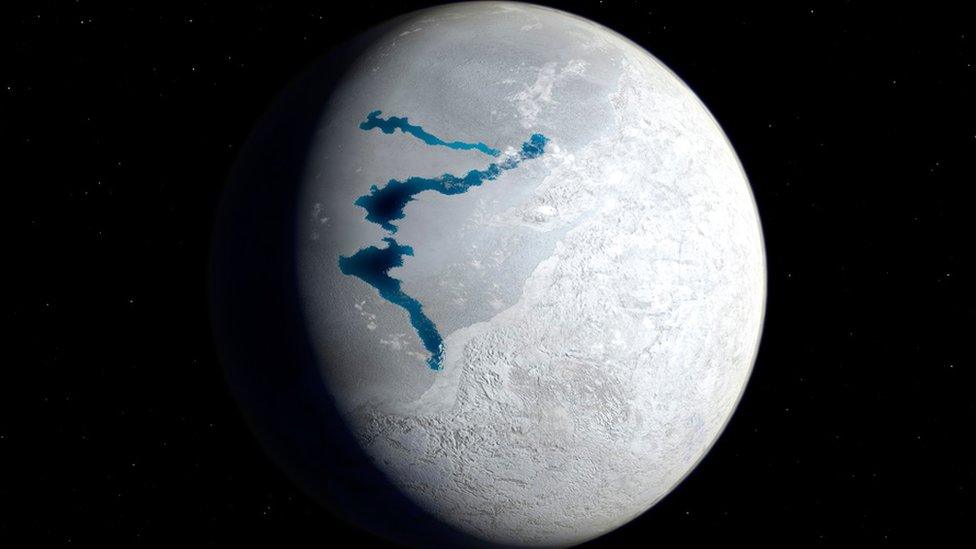

More than 650 million years ago, Earth froze over even down to the equator

Cambridge University palaeontologist Nick Butterfield has said the period "was arguably the most revolutionary in Earth history", and not just because of the rapid biological changes. There were violent swings in climate, too, that experts have long suspected are intertwined.

The context was a planet that previously had long had life-sustaining oceans and a benign climate. Yet, for over three billion years - since 3.8 billion years before present according to most estimates - all life was single-celled, mostly bacteria; little evolutionary innovation had happened.

Algae, more complex than bacteria but still single-celled, had themselves been around for over a billion years (the "boring billion" some palaeontologists call it), but without making much of an ecological impact.

Large, complex organisms appear in the fossil record from about 600 million years ago

With their DNA packed away safely inside a nucleus (so-called eukaryotes, like all animals and plants today), they had an evolutionary advantage over bacteria they seemed unable to exploit.

That changed about 650 million years ago, according to the new study.

There are no fossils of the algae. Instead, Brocks and his team at the Australian National University, have tracked down molecular remnants of their cell walls, molecules closely related to the cholesterol in our bodies, "the most stable thing of any organism - fat," Brocks quips.

After every other trace of the cells had decayed, these fat molecules remained and were absorbed into sediments, and over geological time became cemented into the bedrock of Australia. To be drilled up and analysed hundreds of millions of years later.

"The signals that we find show that the algal population went up by a factor of a hundred to a thousand and the diversity went right up in one big bang, and never went back again," Brocks says.

This ecological flip happened just after one of the greatest environmental catastrophes the planet has ever seen - the "Snowball Earth" period when ice extended from pole to pole, and even at the equator temperatures could have plunged to minus 60 degrees.

The episode ended after 50 million years, when the build-up of volcanic CO2 in the atmosphere created a supergreenhouse that melted the ice in a second cataclysm.

The study was led by ANU's Amber Jarrett (L) and Jochen Brocks (R)

The connection, Brocks believes, is that glacial action ground up continental rocks, releasing the nutrient phosphate which was then washed into the oceans as the thaw progressed.

Today's agricultural green revolution is dependent on phosphates dug up in giant mines around the world, and the pre-Cambrian biological revolution may have been powered the same way, the researchers believe.

"This rise in algae happens just around the time the first animals appeared on the scene," Brocks explains. "It was algae at the bottom of the food web that created this burst of energy and nutrients that allowed larger and more complex creatures to evolve."

Yale University's Noah Planavsky, whose study earlier this year [Nature link] revealed the phosphate nutrient outburst following the Snowball Earth, says the new revelations are "incredibly important".

"It gives the first evidence of ecosystems dominated by complex lifeforms - the eukaryotes," he told the BBC.

Blue whale: An "escalating arms race" resulted in the diversity we see today

In a commentary also in Nature, Andrew Knoll of Harvard University, a world authority on pre-Cambrian life, says the new work makes "a substantial contribution" to revealing "the relationship between life and the surrounding physical environment" at a critical time in animal evolution.

"Food source changes might have helped to pave the way for the animal radiation," he agrees, though adding "key questions remain".

Getting the data was painstaking work, says MIT's Roger Summons, who has previously collaborated with Brocks. The nanogram traces of pre-Cambrian oil measured in the study had to be picked out from a fog of contamination made by fossil fuels.

"I applaud Jochen's insight and his tenacity," Summons wrote in an e-mail. "The results show how fastidious attention to detail ultimately pays off."

However, he suggests the tale is not complete. Likewise, Cambridge University's Nick Butterfield, while accepting the data, disagrees with the interpretation.

In fact, he thinks that Brocks has got cause and effect back to front; the explosion of algae did not drive the rise of animals, he says.

"There's no evidence for animal evolution being constrained by a shortage of food," he argued in an e-mail.

Instead, he says, it was the rise of animals - sponges to be precise - that cleared the ecological path for algae.

Brocks and Butterfield debated the interpretation in the corridors of the Goldschmidt geochemistry conference in Paris this week, external, as others looked on.

Brocks remains unswayed - that the outburst of algae 650 million years ago "kicked off an escalating arms race" in which larger creatures, fuelled by their ocean-grazing, become prey to yet larger ones - until you end up with the complexity we see today.