'Alarmingly high' levels of arsenic in Pakistan's ground water

- Published

This study says that arsenic in groundwater in Pakistan is far more widespread than previously thought

Up to 60 million people in Pakistan are at risk from the deadly chemical arsenic, according to a new analysis of water supplies.

The study looked at data from nearly 1,200 groundwater quality samples from across the country.

The resulting risk map shows concentrations well above World Health Organization (WHO) safety guidelines across the Indus plain.

The research has been published, external in the journal, Science Advances.

Arsenic is a semi-metallic element found all over the world in varying concentrations. Humans come into contact with it because it leaches into groundwater from rocks and sediments.

A map showing the concentrations of arsenic in the water along the Indus plain

The WHO says about 150 million people around the world rely on groundwater contaminated with arsenic.

Long-term exposure can lead to a variety of chronic health conditions, including skin disorders, cancers of the lung and bladder as well as cardiovascular issues.

The WHO has established a level of 10 micrograms per litre as the permissible concentration in drinking water. In Pakistan, the government says that 50 micrograms per litre is acceptable.

This new study shows that 50-60 million people living in the Indus valley, which runs through much of eastern Pakistan, are drinking water which very likely exceeds their government's safe level.

The scientists collected ground water samples, taken from wells going down into the Earth, at 1,200 sites throughout the country. The team then used statistical methods to construct a "hazard map" and to estimate the size of population exposed to the threat.

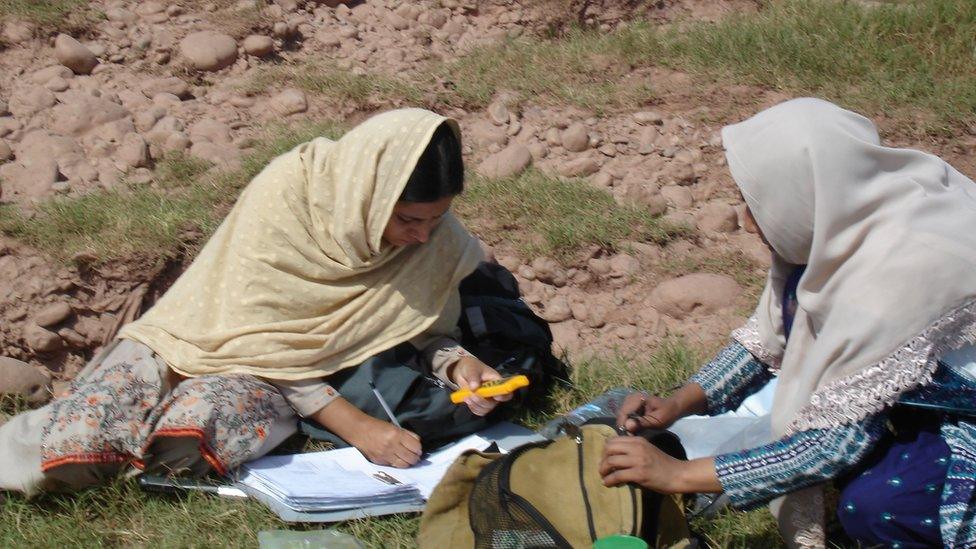

Scientists at work in the field collecting water samples

Lead author Dr Joel Podgorski from the Swiss Federal Institute of Aquatic Science and Technology told BBC News that the findings were "alarming".

"This is the first time we've been able to show the full extent of the problem in Pakistan. Because of the geology and the soil properties and based on all of the measurements we've taken, basically the whole Indus plain is at high risk of having high arsenic levels in the groundwater."

The researchers say that one important cause of the problem is that the sediments that contain the arsenic are relatively young.

So if an aquifer has developed since the end of the last ice age around 10,000 years ago, it's more likely to have higher levels of arsenic in the water than older, deeper aquifers where most of the chemical has leached away.

The scientists also believe that irrigation for farming is making the situation worse. The study found a strong correlation between high soil PH levels and arsenic concentrations.

"There is massive irrigation in the Indus valley, it's a very hot and dry climate," said Dr Podgorski.

"If you have a lot of water flooding the surface that is going to percolate down to the aquifer, that would be an easy way of bringing any released arsenic down to the groundwater."

The number of people who are likely impacted in Pakistan, according to the study, far exceeds the 20 million affected in China. Some researchers, who welcomed the study, have reservations about the scale of the impact.

For David Polya, professor of environmental chemistry at the University of Manchester, there is a "considerable amount of uncertainty in the new figures".

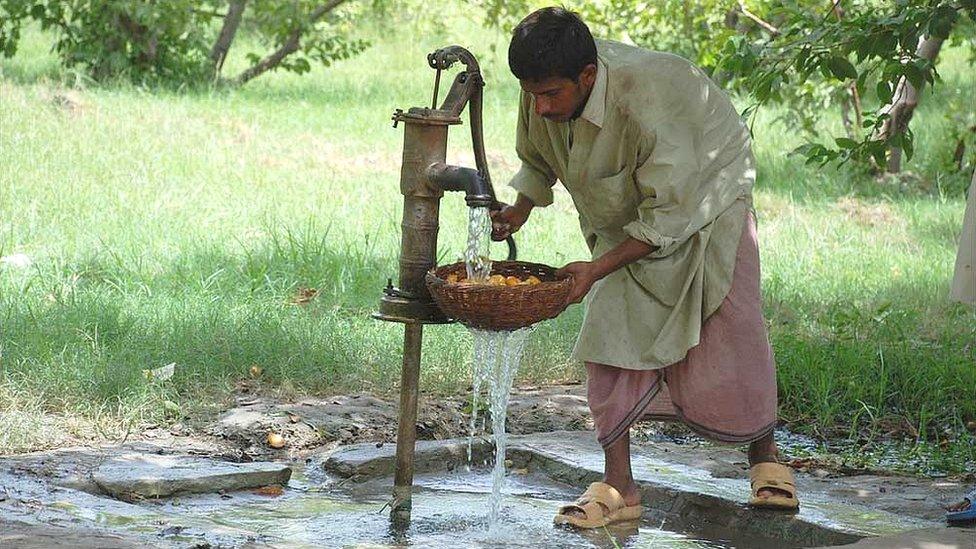

Testing individual wells in the Indus valley is the best way to get a grip on the problem, say scientists

"Even if the population at risk was only half that estimated, it would mean that the estimates of the number of people around the world impacted by such high arsenic hazard groundwaters would need to be substantially upwardly revised," he said.

"This reflects a trend over the the last few decades, where increasing numbers of people have been recognised to be exposed to high arsenic concentrations in their drinking water.

"As further detailed studies such as this are conducted in other areas, no doubt the number of people known to be exposed to this poison through drinking water will further increase."

Other researchers in the field say that whatever the overall accuracy of the numbers, the study is bringing much-needed attention to an under-reported issue.

"This new study contributes information on the causes and extent of arsenic contamination that will be useful for Pakistan as well as for the broader water sector," said Dr Rick Johnston from the WHO.

"It points out the need for robust water quality surveillance and for either avoiding arsenic in drinking water by exploiting arsenic-free resources, or effectively removing arsenic from drinking water supplies."

The only way to get a definitive answer to the scale of exposure is to do more testing on the ground, says Dr Podgorski, the lead author.

"Ultimately, what our map shows is that this whole area should really be tested," he said.

"Some are fine, some are not, you need to go through every step to test each well."

Follow Matt on Twitter, external and on Facebook, external.