What's really the point of wasps?

- Published

A new citizen science survey aims to shed light on that fixture of summertime in the outdoors: the wasp. Though much maligned, these fascinating creatures perform a vital ecological role, say scientists.

The only thing more certain to spoil an August Bank Holiday weekend BBQ than a sudden cloudburst? The arrival of wasps.

At this time of the year, it can sometimes seem as if every outdoor activity is plagued by these yellow-and-black striped insects buzzing around your head and landing on your food and drink.

Wasps aren't just annoying - if you are unlucky, you might end up with a sharp reminder that wasps, like their close relatives the honeybee, pack a powerful sting. That combination of nuisance and pain makes wasps many people's least favourite animals.

Perhaps more than any other insect, wasps are badly in need of a change in public opinion. As well as having fascinating lives, they are extremely important in the environment and face problems similar to those of their cherished, but often no less annoying, cousins the bees.

As the summer approaches its end, many will wish for it, but a world without wasps would most certainly not be a better place.

Social types

The insects we most commonly identify as "wasps" are the social wasps. Social wasps (called yellow-jackets in some places) live in colonies consisting of hundreds or thousands of more-or-less sterile female workers and their much larger mother, the egg-laying queen.

The handful of colony-living, nest-building species is just a tiny fraction of overall wasp diversity, estimated at more than 9,000 species in the UK alone. Most wasps are solitary, some are tiny (a few species practically microscopic), none ever bother us and virtually all are overlooked.

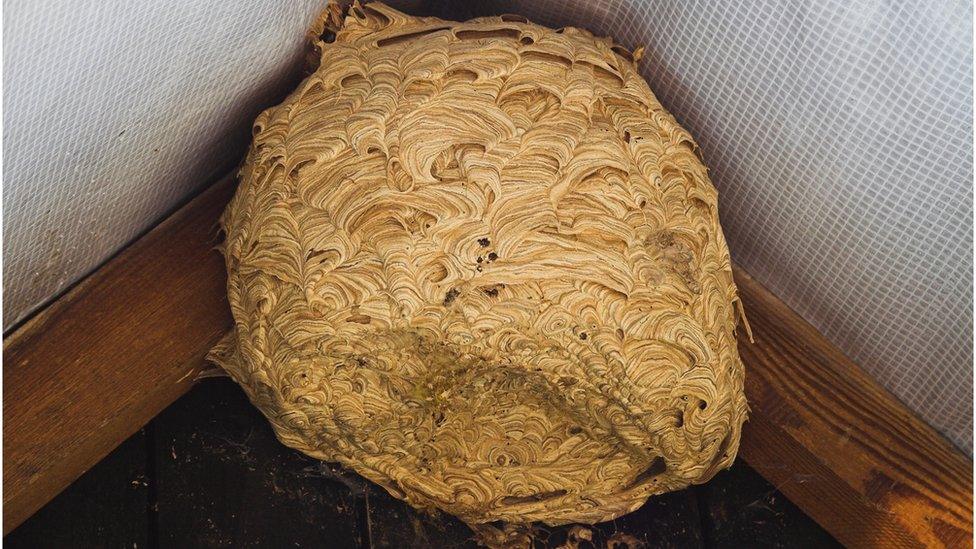

Social wasp nests are constructed from wood fibres collected and then mixed with water by industrious wasp workers to make a kind of papier maché capable of producing very strong and long-lasting structures. The nests start to develop in late spring, when queen wasps emerge from hibernation.

Building a small nest of just a few paper cells, the queen must rear the first set of workers alone before the first batch of worker wasps can start to take over the work required by the developing colony.

Social wasps make nests from wood fibres mixed with water, to create a kind of papier mache

Wasp workers toil ceaselessly to raise their sister workers from eggs the queen lays, cooperating and communicating in intricate ways to build and defend the nest, collect food and look after the queen. When the colony is large enough the workers start to give some young larvae more food at a much greater rate than usual, triggering genetic switches that cause the development of a potential queen rather than a worker.

Male wasps, who take no part in the social life of the colony, develop from unfertilised eggs in a form of sex determination called haplodiploidy, also found in bees and ants. These male-destined eggs are laid by the queen and rarely by workers, some of whom retain the ability to lay eggs but lack the ability to mate.

Potential queens (called gynes before they head a colony) and males, sisters and brothers of the workers, are the reproductive future of the colony. Mating with males from other colonies, the gynes overwinter before starting a colony of their own the following spring.

They may not make honey, but nonetheless wasps have just as fascinating social lives as the celebrated honeybee.

Vital role

Wasps are also just important in the environment. Social wasps are predators and as such they play a vital ecological role, controlling the numbers of potential pests like greenfly and many caterpillars.

Indeed, it has been estimated that the social wasps of the UK might account for 14 million kilograms of insect prey across the summer. A world without wasps would be a world with a very much larger number of insect pests on our crops and gardens.

As well as being voracious and ecologically important predators, wasps are increasingly recognised as valuable pollinators, transferring pollen as they visit flowers to drink nectar. It is actually their thirst for sweet liquids that helps to explain why they become so bothersome at this time of year.

By late August, wasp nests have very large numbers of workers but they have stopped raising any larvae. All the time nests have larvae, the workers must collect protein, which accounts for all those invertebrates they hunt in our gardens. The larvae are able to convert their protein-rich diet into carbohydrates that they secrete as a sugary droplet to feed the adults.

With no larvae, all those adult wasps must find other sources of sugar - hence why they are so attracted to our sugar-rich foods and drinks. When you combine that hunger for sugar with nice weather and our love of eating and drinking outside, the result is inevitable.

A new study is taking advantage of wasps' love of our drinks to find out more about these fascinating and undervalued insects. Calling on members of the public to help, the Big Wasp Survey, external is asking people to build a simple wasp trap from a drinks bottle and a small volume of beer.

Scientists from University College London (UCL) and the University of Gloucestershire want to collect and study the contents of these beer traps. The project, in conjunction with BBC's Countryfile and sponsored by the Royal Entomological Society, hopes to find out which species of wasps live where in the UK, and provide some baseline data for an annual Big Wasp Survey over the coming years.

As Dr Seirian Sumner (UCL) says: "The black and yellow wasps that bother us at picnics are social wasps and we would like to find out much more about where they live and how common they are; to do that we need the public's help".

Insects are generally having a hard time; changing environments, changing climate, habitat loss and the use of insecticides are all taking their toll on these vital creatures.

Yet, whilst many take up the cause of the honeybee or extol the beauty of butterflies some of the most fascinating and important insects remain the most reviled. It's time we stopped asking "what is the point of wasps" and started to appreciate them for the ecological marvels that they are.

- Published19 September 2018

- Published17 September 2017