Science funding: Will 'picking winners' work?

- Published

- comments

In the 1980s, a Conservative government planned to make Britain's computer industry the best in the world by subsidising its research

An ambitious Conservative minister has set out a strategy to turn the UK's scientific expertise into new products and services that will generate jobs and wealth for the economy.

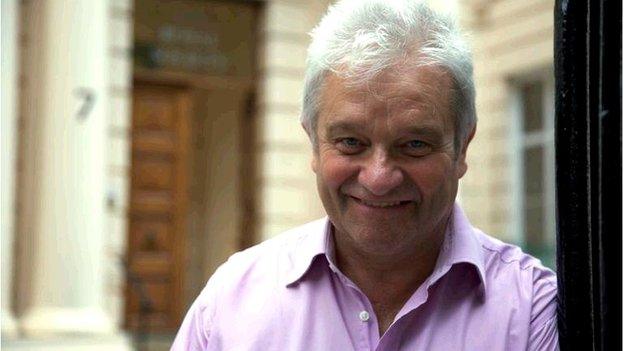

That was in 1983. The minister was Kenneth Clarke, who launched the £350m Alvey programme. It was designed to propel Britain to the forefront of advanced computing.

But the policy of government subsidies for the research and development of favoured companies - known as "picking winners" - did not fit in with Margaret Thatcher's policy of introducing free market principles to the economy. Five years after its inception, the government pulled the plug on the Alvey programme.

Thirty five years on, another Mr Clark, the Business Secretary, Greg Clark, announced £140m to support collaboration between industry and academia in the so-called life sciences sector, which develops innovative new medical treatments.

The money was announced earlier this year - but details were revealed on Wednesday, to great fanfare.

"The life sciences industry is the most successful and most important we know," Mr Clark told reporters.

"Demand for this is going to increase in the years ahead, so what we are doing is to support a collaboration to get breakthroughs for patients and also create jobs."

The government's 1980s industrial strategy was led by an ambitious young minster, Ken Clarke

So why is another Conservative government reviving a policy of subsidising industrial research when an earlier one junked it in the 1980s?

It is because some high-tech companies and leading scientists have persuaded the Treasury and Downing Street that the policy was not wrong back then and should be given another go now.

As a result, the prime minister and the chancellor announced an industrial strategy late last year.

It is to be driven by UK research strengths, and they gave an extra £4.7bn pounds to spend on science over the next four years.

The life sciences strategy is the first announcement of many that will aim to harness Britain's scientific strengths to benefit the economy.

Business Secretary Greg Clark (far right) had a spell as science minister

And while the word "intervention" does not sit easily with some Conservative politicians, the policy is being sold as part of the solution in the government's Brexit narrative.

The formerly Remain-supporting Jeremy Hunt said: "When we leave the EU, we will have a lot of money that we currently didn't have control over.

"What we are saying today is the life science industries [have a] very big opportunity.

"The government is backing those businesses that want Britain to be right at the very top of the pile to make those innovations."

Until recently, the Treasury has been suspicious of the way the nine separate scientific funding bodies spend public money.

The process involves experts in the field deciding allocations based purely on scientific excellence.

But the lack of coordination or strategic oversight made civil servants and ministers nervous of giving the funding bodies any serious money.

That began to change in 2015, when Nobel Prize winner and director of the Crick Institute, Prof Sir Paul Nurse, persuaded the then Chancellor, George Osborne, that an umbrella body should be set up to both coordinate science funders and to consider how the research they were supporting fitted in with economic opportunities.

The Treasury loved the idea. It was a marked departure from the autonomy the funding bodies had enjoyed in the past.

But Sir Paul said proper oversight and coordination was the only way the UK could maintain its research excellence.

George Osborne was persuaded that the science base could be harnessed to benefit the UK economy, when he was chancellor

Government accepted Sir Paul's idea and set up the umbrella body, called United Kingdom Research and Innovation (UKRI).

With it came the extra £4.7bn for science, with the possibility of more, maybe even much more, to come if the system delivers benefits to the economy.

"It is a massive sum that we haven't seen for decades that has been added to the science budget. So, I think we have everything to play for," says Sir Paul.

There is concern though that ministers will interfere, directing funding away from the best research and toward those areas that are socially, economically and politically important to them.

Sir Paul believes such concerns to be "scaremongering".

"For science to play its proper role in promoting benefit for society it's very important to invest in [pure] research," he says, "but also to think about how those fundamental discoveries may be translated into useful objectives that will bring advances for society."

Prof Sir Paul Nurse is the mastermind behind the new funding strategy

Thirty five years on from the launch of the Alvey programme, do we have another Conservative government that is not afraid of picking winners?

The author of the new life sciences strategy document, Prof Sir John Bell, of Oxford University says he hopes so.

"If you look around the world, it's important to think why you're doing an industrial strategy, and I think it's to try to identify sectors where you are likely to see very substantial economic expansion," he says.

"Everyone thinks that the US is a completely capitalist free-market enterprise, but the truth is they pour billions of pounds into subsidising their life sciences industry in a whole variety of different ways."

Follow Pallab on Twitter., external

- Published4 July 2017

- Published19 November 2015