Prehistoric reptile's last meal revealed

- Published

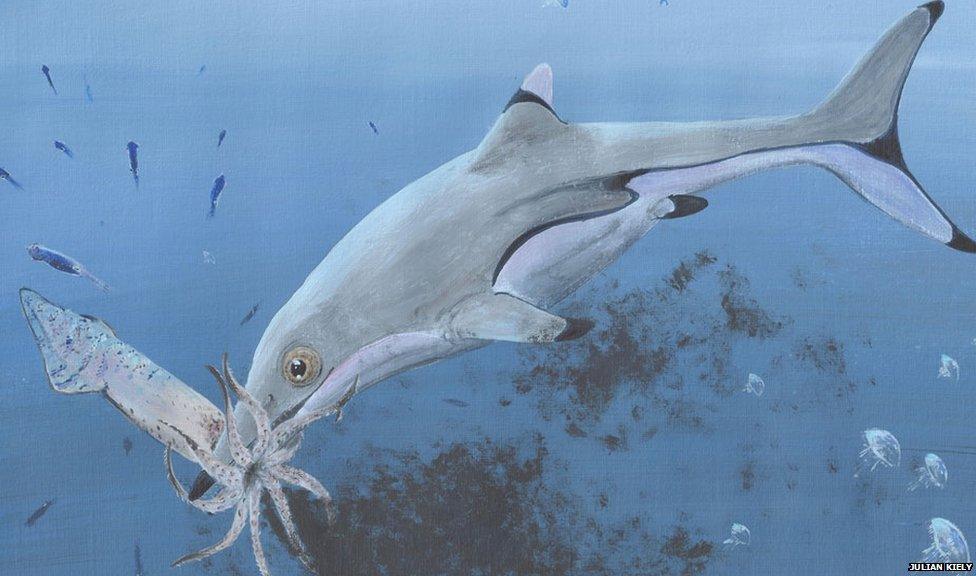

What the ichthyosaur might have looked like

The fossil of a marine reptile that lived 199 million years ago has been identified as a newborn that ate squid as its last meal.

The reptile was an ichthyosaur, which gave birth to live young.

It belongs to the group Ichthyosaurus communis, which was the first species of ichthyosaur to be recognised by science in 1821.

The "exceptional" specimen is the first juvenile of its species to be identified, say researchers.

The reptile had remnants of squid inside its stomach when it died.

"Many tiny hook-like structures are preserved between the ribs," said Dean Lomax of the University of Manchester, UK.

"These are from the arms of prehistoric squid. So, we know this animal's last meal before it died was squid."

Ichthyosaurs occupy a special place in the history of fossil collecting in the UK.

The ichthyosaur measures about 70cm (2.3ft) long

Many of the first specimens were collected along the Dorset coast or in quarries in Somerset in the 19th Century.

About 1,000 fossils are held in museums and other collections around the world. Yet, there are very few specimens of newborns and most are incomplete.

The specimen was identified as a juvenile from the shape of its skull bones.

"This specimen is practically complete and is exceptional," said Dean Lomax.

Nigel Larkin of the University of Cambridge recognised the importance of the fossil when he was examining specimens from the Lapworth Museum of Geology at the University of Birmingham.

However, there was no record of where the fossil was collected or its age.

Researchers at the University of Birmingham analysed a tiny section of rock around the skeleton for the presence of microfossils.

They deduced that the ichthyosaur hails from around 199-196 million years ago. The signature of the rock suggests it originally came from what is now Gloucestershire.

"Many historic ichthyosaur specimens in museums lack any geographic or geological details and are therefore undated," said Nigel Larkin. "This process of looking for microfossils in their host rock might be the key to unlocking the mystery of many specimens."

The study has been published in the journal Historical Biology.

Follow Helen on Twitter, external.

- Published28 August 2017