100 Women: The ice ceiling that held women back from Antarctic exploration

- Published

For decades, there was a ceiling not of glass but of ice, for women in science - the continent of Antarctica.

The heroic tradition of polar exploration conducted solely by men, external meant that Antarctica itself was often thought of as a woman to be conquered.

US Navy Admiral Richard Byrd described it as "an enchanted continent in the sky, pale like a sleeping princess".

Women were not permitted a role in this age of adventure. But not for lack of trying.

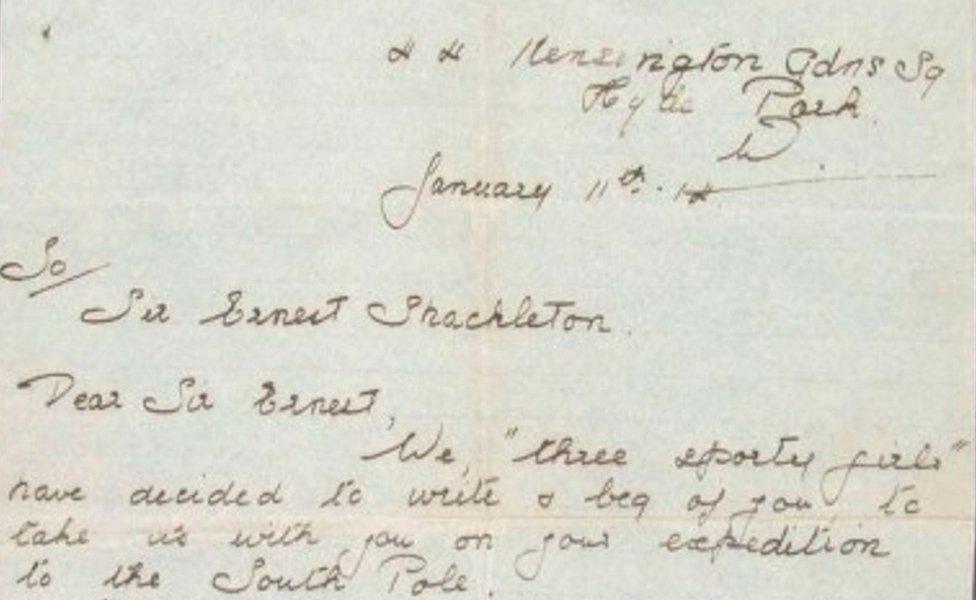

Sir Ernest Shackleton refused the request of "three sporty girls" who wrote to him in 1914, seeking a place in his Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition because they "[did] not see why men should have all the glory, and women none…"

There is also evidence, says Antarctic historian Morgan Seag, that 1,300 women applied to join a proposed British expedition in 1937. All were denied, she tells 100 Women.

Russian geologist Maria Klenova was the first woman to conduct research in the Antarctic, in 1956. Argentine scientists followed a decade later. But some countries were slower to thaw, with the US and UK only reversing their formal bans in the late 1960s and 70s.

The apparent moral peril of mixed accommodation was one argument against including women. Janet Thompson, the first woman to go south with the British Antarctic Survey (BAS), had to informally convince the wives of her teammates that she was going as a serious scientist, Seag explains.

Another application was turned down by BAS, external as "there were no facilities for women in the Antarctic… no shops… no hairdressers".

Unsurprisingly, tenacity is a common theme amongst early female polar scientists.

Geologist Sudipta Sengupta tells 100 Women that she wrote to India's Department of Ocean Development in 1982 declaring her interest in the country's second Antarctic expedition.

A year later, she and marine biologist Aditi Pant became the first Indian women to set foot on the continent.

The team's mission was to set up India's first station in Antarctica - Dakshin Gangotri.

Sengupta remembers having to fight the idea that she was an "ornamental part" of the expedition team.

"I assumed all kinds of responsibilities - both scientific and tasks that required physical labour… You have to consider yourself equally capable as a man in everything you do," she recalls.

Meanwhile in Germany, doctor Monika Puskeppeleit was fighting a similar battle. Fascinated by the medical challenges of overwintering in the Antarctic, where brutal weather isolates teams from civilisation for up to nine months, she first began appealing to Germany's polar research institute in 1984.

Puskeppeleit's campaign attracted letters from other German women, mostly scientists, keen to take part. But resistance was strong.

"They didn't want to have mixed teams on an Antarctic base," she explains to 100 Women. "[I was told] this is not possible for women in this century."

Ironically, the eventual compromise turned out to be more groundbreaking than Puskeppeleit anticipated.

What men said about women going to Antarctica

"There are some things women don't do. They don't become Pope or President or go down to the Antarctic." - Harry Darlington, 1947

"Women will not be allowed in the Antarctic until we can provide one woman for every man" - Rear Admiral George Dufek, 1957

"Antarctica [will] remain the womanless white continent of peace" - Admiral F E Bakutis, 1965

In 1989, she led the first all-female team to overwinter in Antarctica. They arrived at the Georg-von-Neumayer station to take over from a male crew who had heard little of the transition that was about to occur.

"I will not say they were jealous, but they did not like it at all," she remembers.

Buried under nine metres of ice, the team spent 14 months in the Antarctic, with Puskeppeleit as base leader and medical doctor.

She found it challenging, with only a radio for contact with the outside world, but exhilarating. "You have to learn a high respect for nature... You have to pay attention. If you don't have respect for nature you will lose."

So what is it like to work in Antarctica now?

What is 100 Women?

BBC 100 Women names 100 influential and inspirational women around the world every year. This week marks 150 years since the birth of Marie Curie and we are celebrating women in science all week. Join us on Facebook, external, Instagram, external and Twitter, external, and let us know about your favourite scientists on #100Women

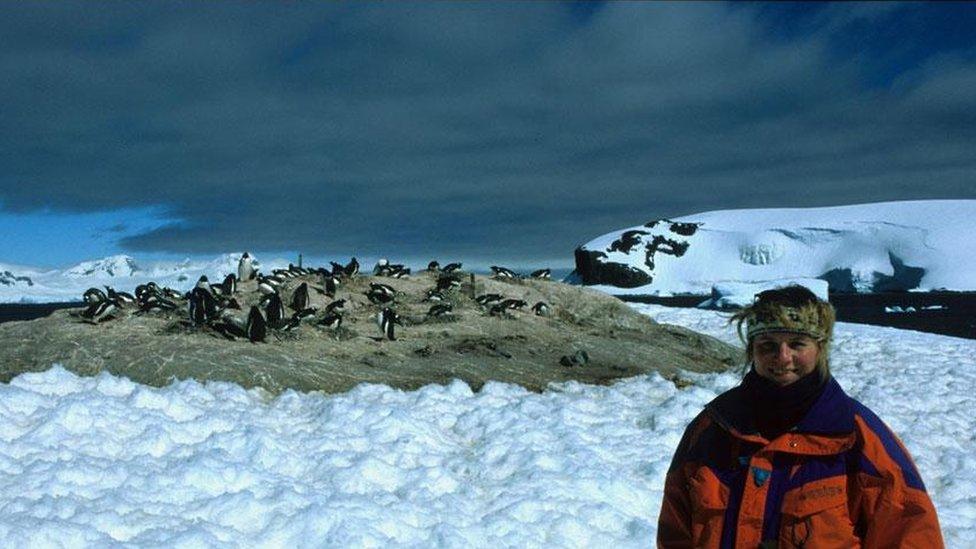

"Like living in your very own natural history documentary," says Dr Jess Walkup, "surrounded by seals, penguins and the occasional whale."

Having just spent her third winter on the continent, Walkup is base leader at Rothera Station on the Antarctic peninsula.

"My first overwinter I was the only woman, but my fellow winterers didn't treat me any differently," she explains to 100 Women.

Yet women are still less likely to overwinter than men. This is, Walkup feels, largely down to the nature of the support roles necessary to keep the base running in harsh conditions, with mechanics, plumbers and engineers coming from commonly male-dominated trades.

"There are not normally a high proportion of women on the stations, maybe between 10% and 25%, and I have found that the women I have worked with generally share a kind of extra camaraderie," says Dr Walkup.

Prof Michelle Koutnik, who has made regular research trips to the Antarctic since 2004, also feels that things have improved for women in science on the continent.

"I have always felt that there were role models, even if women are not the majority," she says of studying glaciers near McMurdo Station.

While Antarctica may no longer be the sole domain of men, barriers are still being broken in many areas. This year marked the first in which women have overwintered at both stations in the Indian Antarctic Programme.

But for the women working there, it's just another year on the ice.

"When you are part of a historic moment," Sudipta Sengupta observes, "you do not realise it.

"Looking back, you understand it was a defining moment."

Additional reporting by Ritwika Mitra.