Antarctic base comes out of deep freeze

- Published

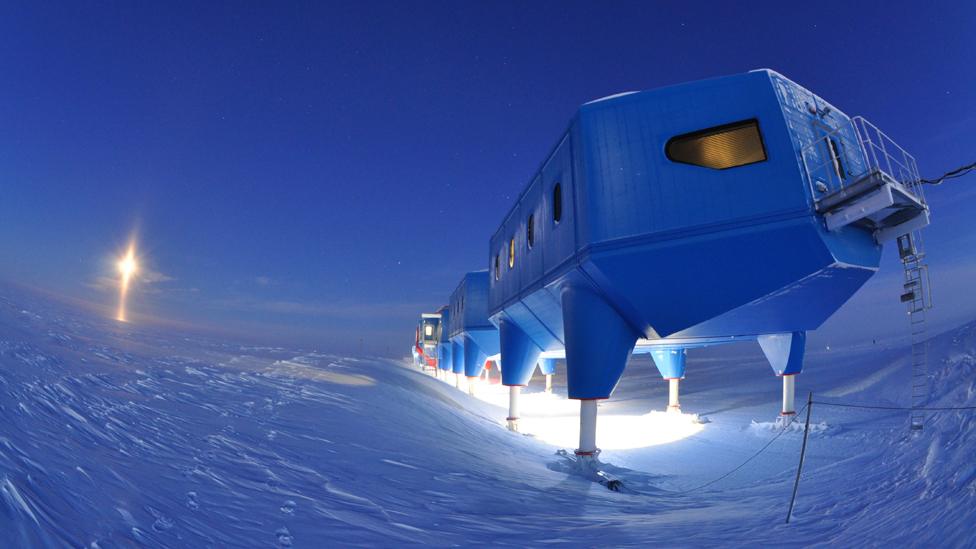

In good shape: Halley station is now being readied for the summer season

The advance party sent in to open up Britain’s mothballed Antarctic base have found no damage.

Halley station was closed in March and staff withdrawn because of uncertainty over the behaviour of cracks in the Brunt Ice Shelf - the flowing, floating platform on which it sits.

The base was secured and left to the elements, with temperatures dipping down to around -50C.

But the first arrivals say Halley is none the worse for its shut-down.

The British Antarctic Survey (BAS) flew a party of 12 into the base to start switching all the utilities back on - the power and heating.

One fear was that windows might have broken in a storm and that this could have allowed snow to get inside. But that has not been the case.

Halley operations manager John Eager said: "The team was very pleased to find the station in such good shape. It's testament to how well last season's team carried out the shut-down just after we successfully re-located the modules 23km inland.

"Apart from a few carpet tiles lifting, and some crazing on inner glazing, everything is exactly as we left it. It is early days in the season, and many complex challenges remain, but it's a great start by the team on the ice."

Some further technical investigations are being carried out to assess how well all the materials and equipment faired during winter.

Halley should be occupied year-round

Halley is now being prepared for the annual southern summer influx of scientists in the coming weeks.

The Royal Research Ship Ernest Shackleton is also expected soon with supplies.

Together with the Rothera base on the Antarctic Peninsula, Halley spearheads British activity on the White Continent.

The station gathers important weather and climate data, and it played a critical role in the research that identified the ozone "hole" in 1985.

In recent years, Halley has also become a major centre for studying solar activity and the impacts this can have on Earth.

Some detailed technical investigations continue at Halley

Halley is supposed to be a year-round station, but its position on the 150m-thick Brunt Ice Shelf has always had a bearing on its operations.

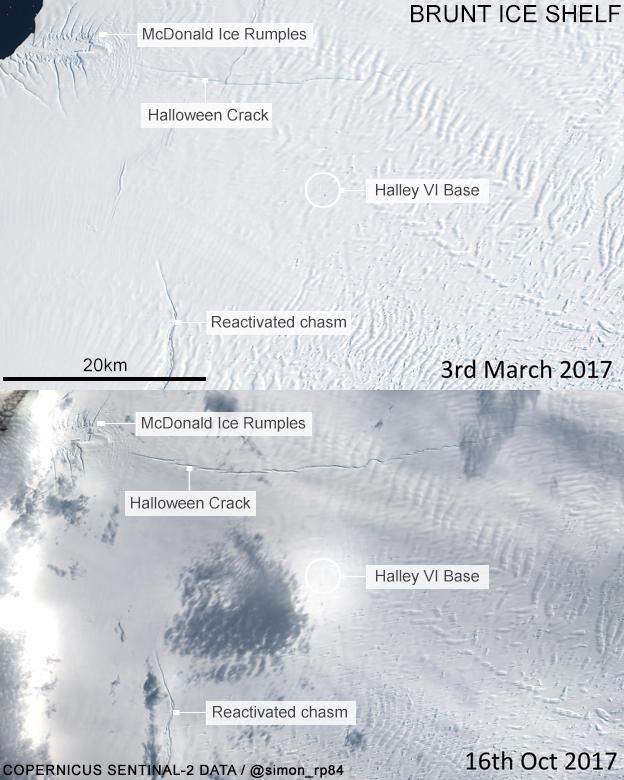

Two fissures are spreading across the shelf. One is a large chasm cutting in front of the base on its seaward side, the other is a long, arcing split that is moving eastwards and away from Halley.

Both fissures are set to spawn big icebergs.

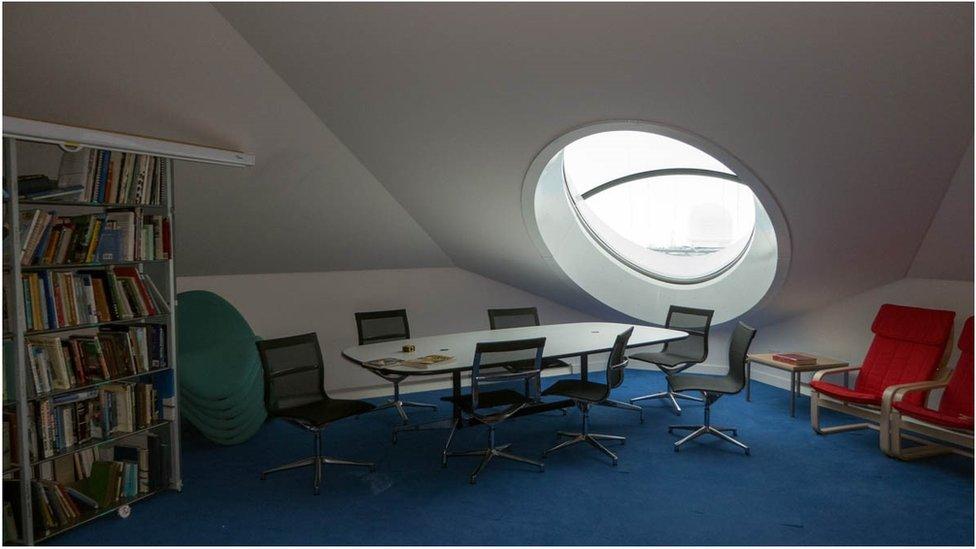

Halley's library: The facilities will soon be in use by scientists

The concern for glaciologists is that both cracks run near to a feature known as the McDonald Ice Rumples. This is a raised area of seafloor that helps pin the shelf in place.

“We hope - as we actually predict - that the chasm will not disconnect the shelf from the rumples. But it is a concern that if that were to happen we don’t know what the stability of the shelf will be in the long term,” BAS science director Prof David Vaughan told BBC News.

The summer accommodation blocks and garages

It is this uncertainty that has prompted BAS to make Halley a summer-only base for the time being.

Evacuation is relatively straightforward in the benign months around the turn of the year, but it becomes extremely hazardous when winter weather is coupled with long polar nights (105 days are spent in 24-hour darkness).

En route now to Halley is a so-called micro-turbine - a kind of “jet engine in a box”.

This will be used to power automated instruments next winter when the base is once again in shut-down.

The turbine is designed to run for thousands of hours without servicing and should provide sufficient electricity to warm the experiments.

Scientists are keen to maintain a basic stream from Halley of weather data, ozone readings, and geomagnetic observations.

The uncertainty is how the cracks will connect with the rumples

Jonathan.Amos-INTERNET@bbc.co.uk, external and follow me on Twitter: @BBCAmos, external

- Published31 October 2017